Catherine II Alekseevna the Great (nee Sophie Auguste Frederica of Anhalt-Zerbst, German Sophie Auguste Friederike von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg, in Orthodoxy Ekaterina Alekseevna; April 21 (May 2), 1729, Stettin, Prussia - November 6 (17), 1796, Winter Palace, Petersburg) - Empress of All Russia from 1762 to 1796.

The daughter of Prince Anhalt-Zerbst, Catherine came to power in a palace coup that dethroned her unpopular husband, Peter III.

The Catherine era was marked by the maximum enslavement of the peasants and the comprehensive expansion of the privileges of the nobility.

Under Catherine the Great, the borders of the Russian Empire were significantly moved to the west (sections of the Commonwealth) and to the south (annexation of Novorossia).

The system of state administration under Catherine II was reformed for the first time since.

In cultural terms, Russia finally became one of the great European powers, which was greatly facilitated by the empress herself, who was fond of literary activity, collected masterpieces of painting and was in correspondence with the French enlighteners.

In general, Catherine's policy and her reforms fit into the mainstream of enlightened absolutism of the 18th century.

Catherine II the Great ( documentary)

Sophia Frederick Augusta of Anhalt-Zerbst was born on April 21 (May 2, according to a new style) in 1729 in the then German city of Stettin, the capital of Pomerania (Pomerania). Now the city is called Szczecin, among other territories, it was voluntarily transferred Soviet Union, following the results of the Second World War, Poland and is the capital of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship of Poland.

Father, Christian August Anhalt-Zerbst, came from the Zerbst-Dorneburg line of the House of Anhalt and was in the service of the Prussian king, was a regimental commander, commandant, then governor of the city of Stettin, where the future empress was born, ran for the Dukes of Courland, but unsuccessfully , finished his service as a Prussian field marshal. Mother - Johanna Elizabeth, from the Gottorp ruling house, was the cousin of the future Peter III. The family tree of Johann Elisabeth goes back to Christian I, King of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, the first Duke of Schleswig-Holstein and the founder of the Oldenburg dynasty.

Maternal uncle Adolf-Friedrich was in 1743 elected heir to the Swedish throne, which he entered in 1751 under the name of Adolf-Fredrik. Another uncle, Karl Eytinsky, according to the plan of Catherine I, was to become the husband of her daughter Elizabeth, but died on the eve of the wedding celebrations.

Catherine was educated at home in the family of the Duke of Zerbst. She studied English, French and Italian, dances, music, the basics of history, geography, theology. She grew up a frisky, inquisitive, playful girl, she loved to flaunt her courage in front of the boys, with whom she easily played on the Stettin streets. Parents were unhappy with the "boyish" behavior of their daughter, but they were happy that Frederica took care of her younger sister Augusta. Her mother called her as a child Fike or Fikhen (German Figchen - comes from the name Frederica, that is, "little Frederica").

In 1743, the Russian Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, while choosing a bride for her heir, Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, the future Russian emperor, remembered that on her deathbed her mother bequeathed her to become the wife of the Holstein prince, brother of Johann Elizabeth. Perhaps it was this circumstance that tipped the scales in Frederica's favor; earlier, Elizabeth had vigorously supported her uncle's election to the Swedish throne and had exchanged portraits with her mother. In 1744, the Zerbst princess, together with her mother, was invited to Russia to marry Peter Fedorovich, who was her second cousin. For the first time she saw her future husband in Eitinsky Castle in 1739.

Immediately after her arrival in Russia, she began to study the Russian language, history, Orthodoxy, Russian traditions, as she sought to get to know Russia as fully as possible, which she perceived as a new homeland. Among her teachers are the famous preacher Simon Todorsky (Orthodoxy teacher), the author of the first Russian grammar Vasily Adadurov (Russian language teacher) and choreographer Lange (dance teacher).

In an effort to learn Russian as quickly as possible, the future empress studied at night, sitting at an open window in the frosty air. She soon fell ill with pneumonia, and her condition was so severe that her mother offered to bring a Lutheran pastor. Sophia, however, refused and sent for Simon Todorsky. This circumstance added to her popularity at the Russian court. June 28 (July 9), 1744 Sophia Frederick Augusta converted from Lutheranism to Orthodoxy and received the name Catherine Alekseevna (the same name and patronymic as Elizabeth's mother, Catherine I), and the next day she was betrothed to the future emperor.

The appearance of Sophia with her mother in St. Petersburg was accompanied by political intrigue, in which her mother, Princess Zerbstskaya, was involved. She was a fan of King Frederick II of Prussia, and the latter decided to use her stay at the Russian imperial court to establish his influence on Russian foreign policy. To do this, it was planned, through intrigue and influence on Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, to remove Chancellor Bestuzhev, who pursued an anti-Prussian policy, from the affairs and replace him with another nobleman who sympathized with Prussia. However, Bestuzhev managed to intercept the letters of Princess Zerbst Frederick II and present them to Elizabeth Petrovna. After the latter found out about the “ugly role of a Prussian spy” played by her mother Sophia at her court, she immediately changed her attitude towards her and disgraced her. However, this did not affect the position of Sophia herself, who did not take part in this intrigue.

On August 21, 1745, at the age of sixteen, Catherine was married to Peter Fedorovich, who was 17 years old and who was her second cousin. Early years living together Peter was not at all interested in his wife, and there was no marital relationship between them.

Finally, after two failed pregnancies, On September 20, 1754, Catherine gave birth to a son, Pavel. The birth was difficult, the baby was immediately taken away from her mother at the behest of the reigning Empress Elizabeth Petrovna, and Catherine was deprived of the opportunity to raise, allowing only occasionally to see Paul. So the Grand Duchess saw her son for the first time only 40 days after the birth. A number of sources claim that the true father of Paul was Catherine's lover S. V. Saltykov (there is no direct statement about this in the "Notes" of Catherine II, but they are often interpreted this way). Others - that such rumors are unfounded, and that Peter underwent an operation that eliminated a defect that made conception impossible. The issue of paternity aroused public interest as well.

After the birth of Pavel, relations with Peter and Elizaveta Petrovna finally deteriorated. Peter called his wife “reserve madam” and openly made mistresses, however, without preventing Catherine from doing this, who during this period, thanks to the efforts of the English ambassador Sir Charles Henbury Williams, had a connection with Stanislav Poniatowski, the future king of Poland. On December 9, 1757, Catherine gave birth to a daughter, Anna, which caused great displeasure of Peter, who said at the news of a new pregnancy: “God knows why my wife became pregnant again! I am not at all sure whether this child is from me and whether I should take it personally.

The English ambassador Williams during this period was a close friend and confidant of Catherine. He repeatedly provided her with significant amounts in the form of loans or subsidies: in 1750 alone, 50,000 rubles were transferred to her, for which there are two of her receipts; and in November 1756, 44,000 rubles were transferred to her. In return, he received various confidential information from her - orally and through letters that she quite regularly wrote to him, as if on behalf of a man (for conspiracy purposes). In particular, at the end of 1756, after the start of the Seven Years' War with Prussia (whose ally was England), Williams, as follows from his own dispatches, received from Catherine important information on the state of the warring Russian army and on the plan of the Russian offensive, which he handed over to London, as well as to Berlin, the Prussian king Frederick II. After Williams left, she also received money from his successor, Keith. Historians explain Catherine's frequent appeal for money to the British by her extravagance, due to which her expenses far exceeded the amounts that were allocated for her maintenance from the treasury. In one of her letters to Williams, she promised, in gratitude, “to bring Russia to a friendly alliance with England, to render her everywhere the assistance and preference necessary for the good of all Europe and especially Russia, before their common enemy, France, whose greatness is a shame for Russia. I will learn to practice these feelings, base my fame on them and prove to the king, your sovereign, the strength of these my feelings..

Since 1756, and especially during the illness of Elizabeth Petrovna, Catherine hatched a plan to remove the future emperor (her husband) from the throne by means of a conspiracy, about which she repeatedly wrote to Williams. For these purposes, Catherine, according to the historian V. O. Klyuchevsky, “begged for a loan for gifts and bribery of 10 thousand pounds sterling from English king, having pledged her word of honor to act in the common Anglo-Russian interests, she began to think about involving the guards in the event of the death of Elizabeth, entered into a secret agreement about this with Hetman K. Razumovsky, the commander of one of the guards regiments. Chancellor Bestuzhev was also privy to this plan of a palace coup, who promised Catherine assistance.

At the beginning of 1758, Empress Elizaveta Petrovna suspected Apraksin, the commander-in-chief of the Russian army, with whom Catherine was on friendly terms, as well as Chancellor Bestuzhev himself, of treason. Both were arrested, interrogated and punished; however, Bestuzhev managed to destroy all his correspondence with Catherine before his arrest, which saved her from persecution and disgrace. At the same time, Williams was recalled to England. Thus, her former favorites were removed, but a circle of new ones began to form: Grigory Orlov and Dashkova.

The death of Elizabeth Petrovna (December 25, 1761) and the accession to the throne of Peter Fedorovich under the name of Peter III alienated the spouses even more. Peter III began to openly live with his mistress Elizaveta Vorontsova, settling his wife at the other end of the Winter Palace. When Catherine became pregnant from Orlov, this could no longer be explained by accidental conception from her husband, since communication between the spouses had completely ceased by that time. Ekaterina hid her pregnancy, and when the time came to give birth, her devoted valet Vasily Grigoryevich Shkurin set fire to his house. A lover of such spectacles, Peter with the court left the palace to look at the fire; at this time, Catherine gave birth safely. This is how Alexei Bobrinsky was born, to whom his brother Paul I subsequently awarded the title of count.

Having ascended the throne, Peter III carried out a number of actions that caused a negative attitude of the officer corps towards him. So, he concluded an unfavorable treaty for Russia with Prussia, while Russia won a number of victories over it during the Seven Years' War, and returned the lands occupied by the Russians to it. At the same time, he intended, in alliance with Prussia, to oppose Denmark (an ally of Russia), in order to return Schleswig taken from Holstein, and he himself intended to go on a campaign at the head of the guard. Peter announced the sequestration of the property of the Russian Church, the abolition of monastic land ownership and shared with others plans for the reform of church rites. Supporters of the coup accused Peter III of ignorance, dementia, dislike of Russia, complete inability to rule. Against his background, Catherine looked favorably - a smart, well-read, pious and benevolent wife, who was persecuted by her husband.

After relations with her husband finally deteriorated and dissatisfaction with the emperor on the part of the guard intensified, Catherine decided to participate in the coup. Her comrades-in-arms, the main of which were the Orlov brothers, sergeant major Potemkin and adjutant Fyodor Khitrovo, engaged in agitation in the guards units and won them over to their side. The immediate cause of the start of the coup was the rumors about the arrest of Catherine and the disclosure and arrest of one of the participants in the conspiracy - Lieutenant Passek.

To all appearances, foreign participation has not been avoided here either. As A. Troyat and K. Valishevsky write, when planning the overthrow of Peter III, Catherine turned to the French and the British for money, hinting to them what she was going to implement. The French were distrustful of her request to borrow 60 thousand rubles, not believing in the seriousness of her plan, but she received 100 thousand rubles from the British, which subsequently may have influenced her attitude towards England and France.

In the early morning of June 28 (July 9), 1762, while Peter III was in Oranienbaum, Catherine, accompanied by Alexei and Grigory Orlov, arrived from Peterhof to St. Petersburg, where the guards swore allegiance to her. Peter III, seeing the hopelessness of resistance, abdicated the next day, was taken into custody and died under unclear circumstances. In her letter, Catherine once pointed out that before his death, Peter suffered from hemorrhoidal colic. After her death (although the facts indicate that even before her death - see below), Catherine ordered an autopsy to dispel suspicions of poisoning. An autopsy showed (according to Catherine) that the stomach is absolutely clean, which excludes the presence of poison.

At the same time, as the historian N. I. Pavlenko writes, “The violent death of the emperor is irrefutably confirmed by absolutely reliable sources” - Orlov’s letters to Catherine and a number of other facts. There are also facts indicating that she knew about the impending assassination of Peter III. So, already on July 4, 2 days before the death of the emperor in the palace in Ropsha, Catherine sent the doctor Paulsen to him, and as Pavlenko writes, “It is indicative that Paulsen was sent to Ropsha not with medicines, but with surgical instruments for opening the body”.

After the abdication of her husband, Ekaterina Alekseevna ascended the throne as the reigning empress with the name of Catherine II, issuing a manifesto in which the basis for the removal of Peter was an attempt to change the state religion and peace with Prussia. To justify her own rights to the throne (and not the heir to Paul), Catherine referred to "the desire of all Our loyal subjects is clear and not hypocritical." On September 22 (October 3), 1762, she was crowned in Moscow. As V. O. Klyuchevsky described her accession, “Catherine made a double capture: she took away power from her husband and did not transfer it to her son, the natural heir of her father”.

The policy of Catherine II was characterized mainly by the preservation and development of the trends laid down by her predecessors. In the middle of the reign, an administrative (provincial) reform was carried out, which determined the territorial structure of the country until 1917, as well as a judicial reform. Territory Russian state increased significantly due to the annexation of the fertile southern lands - the Crimea, the Black Sea region, as well as the eastern part of the Commonwealth, etc. The population increased from 23.2 million (in 1763) to 37.4 million (in 1796), in terms of population Russia became the largest European country (it accounted for 20% of the population of Europe). Catherine II formed 29 new provinces and built about 144 cities.

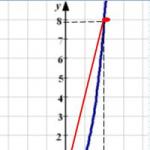

Klyuchevsky about the reign of Catherine the Great: "The army from 162 thousand people was strengthened to 312 thousand, the fleet, which in 1757 consisted of 21 battleships and 6 frigates, in 1790 counted 67 battleships and 40 frigates and 300 rowboats, the amount of state revenue from 16 million rubles. rose to 69 million, that is, more than quadrupled, the success of foreign trade: the Baltic - in increasing import and export, from 9 million to 44 million rubles, the Black Sea, Catherine and created - from 390 thousand in 1776 to 1 million 900 thousand rubles in 1796, the growth of domestic turnover was indicated by the issue of a coin in 34 years of the reign for 148 million rubles, while in the 62 previous years it was issued only for 97 million.

Population growth was largely the result of the accession to Russia of foreign states and territories (where almost 7 million people lived), which often took place against the wishes of the local population, which led to the emergence of "Polish", "Ukrainian", "Jewish" and other national issues inherited by the Russian Empire from the era of Catherine II. Hundreds of villages under Catherine received the status of a city, but in fact they remained villages in appearance and occupation of the population, the same applies to a number of cities founded by her (some even existed only on paper, as evidenced by contemporaries). In addition to issuing coins, 156 million rubles worth of paper banknotes were issued, which led to inflation and a significant depreciation of the ruble; therefore, the real growth of budget revenues and other economic indicators during her reign was much less than the nominal one.

The Russian economy continued to be agrarian. The share of the urban population has practically not increased, amounting to about 4%. At the same time, a number of cities were founded (Tiraspol, Grigoriopol, etc.), iron smelting increased by more than 2 times (in which Russia took 1st place in the world), and the number of sailing and linen manufactories increased. In total, by the end of the XVIII century. there were 1200 large enterprises in the country (in 1767 there were 663 of them). Exports of Russian goods to other European countries have increased significantly, including through established Black Sea ports. However, in the structure of this export there were no finished products at all, only raw materials and semi-finished products, and foreign industrial products dominated in imports. While in the West in the second half of the XVIII century. the Industrial Revolution took place, Russian industry remained "patriarchal" and serfdom, which led to its lagging behind the Western one. Finally, in the 1770-1780s. an acute social and economic crisis broke out, the result of which was a financial crisis.

Catherine's commitment to the ideas of the Enlightenment largely predetermined the fact that, to characterize domestic policy Catherine's time, the term "enlightened absolutism" is often used. She really brought some of the ideas of the Enlightenment to life.

So, according to Catherine, based on the works of the French philosopher, the vast Russian expanses and the severity of the climate determine the regularity and necessity of autocracy in Russia. Based on this, under Catherine, the autocracy was strengthened, the bureaucratic apparatus was strengthened, the country was centralized and the system of government was unified. However, the ideas expressed by Diderot and Voltaire, of which she was an adherent in words, did not correspond to her domestic policy. They defended the idea that every person is born free, and advocated the equality of all people and the elimination of medieval forms of exploitation and despotic forms of government. Contrary to these ideas, under Catherine there was a further deterioration in the position of serfs, their exploitation intensified, inequality grew due to the granting of even greater privileges to the nobility.

In general, historians characterize her policy as “pro-noble” and believe that, contrary to the Empress’s frequent statements about her “vigilant concern for the welfare of all subjects,” the concept of the common good in the era of Catherine was the same fiction as in general in Russia XVIII century.

Under Catherine, the territory of the empire was divided into provinces, many of which remained practically unchanged until the October Revolution. The territory of Estonia and Livonia as a result of the regional reform in 1782-1783. was divided into two provinces - Riga and Revel - with institutions that already existed in other provinces of Russia. The special Baltic order was also eliminated, which provided for more extensive rights than the Russian landowners had for local nobles to work and the personality of a peasant. Siberia was divided into three provinces: Tobolsk, Kolyvan and Irkutsk.

Speaking about the reasons for the provincial reform under Catherine, N. I. Pavlenko writes that it was a response to the Peasant War of 1773-1775. under the leadership of Pugachev, which revealed the weakness of local authorities and their inability to cope with peasant riots. The reform was preceded by a series of memos submitted to the government from the nobility, which recommended that the network of institutions and "police guards" be increased in the country.

Carrying out the provincial reform in the Left-bank Ukraine in 1783-1785. led to a change in the regimental structure (former regiments and hundreds) to a common administrative division for the Russian Empire into provinces and counties, the final establishment of serfdom and the equalization of the rights of the Cossack officers with the Russian nobility. With the conclusion of the Kyuchuk-Kainarji Treaty (1774), Russia received access to the Black Sea and Crimea.

Thus, there was no need to preserve the special rights and management system of the Zaporizhian Cossacks. At the same time, their traditional way of life often led to conflicts with the authorities. After repeated pogroms of Serbian settlers, as well as in connection with the support of the Cossacks of the Pugachev uprising, Catherine II ordered to disband the Zaporozhian Sich, which was carried out on the orders of Grigory Potemkin to pacify the Zaporizhzhya Cossacks by General Peter Tekeli in June 1775.

The Sich was disbanded, most of the Cossacks were disbanded, and the fortress itself was destroyed. In 1787, Catherine II, together with Potemkin, visited the Crimea, where she was met by the Amazon company created for her arrival; in the same year, the Army of the Faithful Cossacks was created, which later became the Black Sea Cossack Army, and in 1792 they were granted the Kuban for perpetual use, where the Cossacks moved, having founded the city of Ekaterinodar.

The reforms on the Don created a military civil government modeled on the provincial administrations of central Russia. In 1771, the Kalmyk Khanate was finally annexed to Russia.

The reign of Catherine II was characterized by the extensive development of the economy and trade, while maintaining the "patriarchal" industry and agriculture. By decree of 1775, factories and industrial plants were recognized as property, the disposal of which does not require special permission from the authorities. In 1763, the free exchange of copper money for silver was banned so as not to provoke the development of inflation. The development and revival of trade was facilitated by the emergence of new credit institutions (state bank and loan office) and the expansion banking operations(since 1770, the acceptance of deposits for storage was introduced). A state bank was established and for the first time the issue of paper money - banknotes - was launched.

State regulation of salt prices introduced, which was one of the vital goods in the country. The Senate legislated the price of salt at 30 kopecks per pood (instead of 50 kopecks) and 10 kopecks per pood in the regions of mass salting of fish. Without introducing a state monopoly on the salt trade, Catherine counted on increased competition and, ultimately, improving the quality of the goods. However, soon the price of salt was raised again. At the beginning of the reign, some monopolies were abolished: the state monopoly on trade with China, the merchant Shemyakin's private monopoly on the import of silk, and others.

The role of Russia in the world economy has increased- Russian sailing fabric began to be exported to England in large quantities, exports of cast iron and iron to other European countries increased (the consumption of cast iron in the domestic Russian market also increased significantly). But the export of raw materials grew especially strongly: timber (by a factor of 5), hemp, bristles, etc., as well as bread. The volume of exports of the country increased from 13.9 million rubles. in 1760 to 39.6 million rubles. in 1790

Russian merchant ships began to sail in the Mediterranean. However, their number was insignificant in comparison with foreign ones - only 7% of the total number of ships serving Russian foreign trade in late XVIII - early XIX centuries; the number of foreign merchant ships entering Russian ports annually increased from 1340 to 2430 during the period of her reign.

As the economic historian N. A. Rozhkov pointed out, in the structure of exports in the era of Catherine there were no finished products at all, only raw materials and semi-finished products, and 80-90% of imports were foreign industrial products, the import volume of which was several times higher than domestic production. Thus, the volume of domestic manufactory production in 1773 was 2.9 million rubles, the same as in 1765, and the volume of imports in these years was about 10 million rubles.

Industry developed poorly, there were practically no technical improvements, and serf labor dominated. So, from year to year, cloth manufactories could not even satisfy the needs of the army, despite the ban on selling cloth "to the side", in addition, the cloth was of poor quality, and it had to be purchased abroad. Catherine herself did not understand the significance of the Industrial Revolution taking place in the West and argued that machines (or, as she called them, “colosses”) were harmful to the state, since they reduced the number of workers. Only two export industries developed rapidly - the production of cast iron and linen, but both - on the basis of "patriarchal" methods, without the use of new technologies that were actively introduced at that time in the West - which predetermined a severe crisis in both industries that began shortly after the death of Catherine II .

In the field of foreign trade, Catherine's policy consisted in a gradual transition from protectionism, characteristic of Elizabeth Petrovna, to the complete liberalization of exports and imports, which, according to a number of economic historians, was a consequence of the influence of the ideas of the Physiocrats. Already in the first years of the reign, a number of foreign trade monopolies and a ban on grain exports were abolished, which from that time began to grow rapidly. In 1765, the Free Economic Society was founded, which promoted the ideas of free trade and published its own magazine. In 1766, a new customs tariff was introduced, which significantly reduced tariff barriers compared to the protectionist tariff of 1757 (which established protective duties in the amount of 60 to 100% or more); even more they were reduced in the customs tariff of 1782. Thus, in the "moderate protectionist" tariff of 1766, protective duties averaged 30%, and in the liberal tariff of 1782 - 10%, only for some goods rising to 20- thirty%.

Agriculture, like industry, developed mainly through extensive methods (increase in the amount of arable land); the promotion of intensive methods of agriculture by the Free Economic Society created under Catherine had no great result.

From the first years of the reign of Catherine, famine began to periodically arise in the village, which some contemporaries explained by chronic crop failures, but the historian M.N. Pokrovsky associated with the beginning of the mass export of grain, which had previously been banned under Elizabeth Petrovna, and by the end of Catherine's reign amounted to 1.3 million rubles. in year. Cases of mass ruin of peasants became more frequent. The famines acquired a special scope in the 1780s, when they covered large regions of the country. Bread prices have risen sharply: for example, in the center of Russia (Moscow, Smolensk, Kaluga) they have increased from 86 kop. in 1760 to 2.19 rubles. in 1773 and up to 7 rubles. in 1788, that is, more than 8 times.

Paper money introduced into circulation in 1769 - banknotes- in the first decade of their existence, they accounted for only a few percent of the metal (silver and copper) money supply, and played a positive role, allowing the state to reduce its costs of moving money within the empire. However, due to the lack of money in the treasury, which became a constant phenomenon, from the beginning of the 1780s, there was an increasing issue of banknotes, the volume of which by 1796 reached 156 million rubles, and their value depreciated 1.5 times. In addition, the state borrowed money from abroad in the amount of 33 million rubles. and had various unpaid internal obligations (bills, salaries, etc.) in the amount of 15.5 million rubles. That. the total amount of the government's debts amounted to 205 million rubles, the treasury was empty, and budget expenditures significantly exceeded revenues, which Paul I stated upon accession to the throne. All this gave rise to the historian N. D. Chechulin in his economic research to conclude that there was a “severe economic crisis” in the country (in the second half of the reign of Catherine II) and “the complete collapse of the financial system of Catherine’s reign.”

In 1768, a network of city schools was created, based on the class-lesson system. Schools began to open. Under Catherine, special attention was paid to the development of women's education; in 1764, the Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens and the Educational Society for Noble Maidens were opened. The Academy of Sciences has become one of the leading scientific bases in Europe. An observatory, a physics office, an anatomical theater, a botanical garden, instrumental workshops, a printing house, a library, and an archive were founded. On October 11, 1783, the Russian Academy was founded.

Compulsory vaccination introduced, and Catherine decided to set a personal example for her subjects: on the night of October 12 (23), 1768, the empress herself was vaccinated against smallpox. Among the first vaccinated were also Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich and Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna. Under Catherine II, the fight against epidemics in Russia began to take on the character of state events that were directly within the responsibilities of the Imperial Council, the Senate. By decree of Catherine, outposts were created, located not only on the borders, but also on the roads leading to the center of Russia. The "Charter of border and port quarantines" was created.

New areas of medicine for Russia developed: hospitals for the treatment of syphilis, psychiatric hospitals and shelters were opened. A number of fundamental works on questions of medicine have been published.

To prevent their resettlement in the central regions of Russia and attachment to their communities for the convenience of collecting state taxes, Catherine II established the Pale of Settlement in 1791 outside of which Jews had no right to reside. The Pale of Settlement was established in the same place where the Jews lived before - on the lands annexed as a result of the three partitions of Poland, as well as in the steppe regions near the Black Sea and sparsely populated areas east of the Dnieper. The conversion of Jews to Orthodoxy removed all restrictions on residence. It is noted that the Pale of Settlement contributed to the preservation of Jewish national identity, the formation of a special Jewish identity within the Russian Empire.

In 1762-1764 Catherine published two manifestos. The first - "On allowing all foreigners entering Russia to settle in which provinces they wish and on the rights granted to them" called on foreign citizens to move to Russia, the second determined the list of benefits and privileges for immigrants. Soon the first German settlements arose in the Volga region, allotted for immigrants. The influx of German colonists was so great that already in 1766 it was necessary to temporarily suspend the reception of new settlers until the settlement of those who had already entered. The creation of colonies on the Volga was on the rise: in 1765 - 12 colonies, in 1766 - 21, in 1767 - 67. According to the census of colonists in 1769, 6.5 thousand families lived in 105 colonies on the Volga, which amounted to 23.2 thousand people. In the future, the German community will play a prominent role in the life of Russia.

During the reign of Catherine, the country included the Northern Black Sea region, the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov, Crimea, Novorossia, the lands between the Dniester and the Bug, Belarus, Courland and Lithuania. The total number of new subjects thus acquired by Russia reached 7 million. As a result, as V. O. Klyuchevsky wrote, in the Russian Empire “the discord of interests intensified” between different nations. This was expressed, in particular, in the fact that for almost every nationality the government was forced to introduce a special economic, tax and administrative regime. Thus, the German colonists were completely exempted from paying taxes to the state and from other duties; for the Jews, the Pale of Settlement was introduced; from the Ukrainian and Belarusian population in the territory of the former Commonwealth, at first, the poll tax was not levied at all, and then it was levied at half the rate. In these conditions, the indigenous population turned out to be the most discriminated against, which led to such an incident: some Russian nobles in the late 18th - early 19th centuries. as a reward for their service, they were asked to “record as Germans” so that they could enjoy the corresponding privileges.

On April 21, 1785, two charters were issued: "Charter on the rights, liberties and advantages of the noble nobility" and "Charter to cities". The empress called them the crown of her activity, and historians consider them the crown of the "pro-noble policy" of the kings of the 18th century. As N. I. Pavlenko writes, “In the history of Russia, the nobility has never been blessed with such a variety of privileges as under Catherine II.”

Both charters finally secured for the upper classes those rights, duties and privileges that had already been granted by Catherine's predecessors during the 18th century, and provided a number of new ones. So, the nobility as an estate was formed by decrees of Peter I and at the same time received a number of privileges, including exemption from the poll tax and the right to unlimitedly dispose of estates; and by decree of Peter III, it was finally released from compulsory service to the state.

The charter to the nobility contained the following guarantees:

Pre-existing rights confirmed

- the nobility was exempted from quartering military units and teams, from corporal punishment

- the nobility received ownership of the bowels of the earth

- the right to have their own estate institutions, the name of the 1st estate changed: not "nobility", but "noble nobility"

- it was forbidden to confiscate the estates of nobles for criminal offenses; estates were to be passed on to legitimate heirs

- the nobles have the exclusive right to own land, but the "Charter" does not say a word about the monopoly right to have serfs

- Ukrainian foremen were equalized in rights with Russian nobles. a nobleman who did not have an officer rank was deprived of the right to vote

- only nobles whose income from estates exceeds 100 rubles could hold elected positions.

Despite the privileges, in the era of Catherine II, property inequality among the nobles greatly increased: against the background of individual large fortunes, the economic situation of part of the nobility worsened. As the historian D. Blum points out, a number of large nobles owned tens and hundreds of thousands of serfs, which was not the case in previous reigns (when the owner of more than 500 souls was considered rich); at the same time, almost 2/3 of all landowners in 1777 had less than 30 male serf souls, and 1/3 of the landlords - less than 10 souls; many nobles who wanted to enter the civil service did not have the means to purchase appropriate clothing and footwear. V. O. Klyuchevsky writes that many noble children in her reign, even becoming students of the Maritime Academy and “receiving a small salary (stipends), 1 rub. per month, “from barefoot” they could not even attend the academy and were forced, according to a report, not to think about the sciences, but about their own food, on the side to acquire funds for their maintenance.

During the reign of Catherine II, a number of laws were adopted that worsened the situation of the peasants:

The decree of 1763 laid the maintenance of the military teams sent to suppress peasant uprisings on the peasants themselves.

By decree of 1765, for open disobedience, the landowner could send the peasant not only into exile, but also to hard labor, and the period of hard labor was set by him; the landlords also had the right to return the exiled from hard labor at any time.

The decree of 1767 forbade peasants to complain about their master; the disobedient were threatened with exile to Nerchinsk (but they could go to court).

In 1783 serfdom was introduced in Little Russia (the Left-bank Ukraine and the Russian Chernozem region).

In 1796, serfdom was introduced in Novorossiya (Don, North Caucasus).

After the partitions of the Commonwealth, the serfdom regime was tightened in the territories that had ceded to the Russian Empire (Right-Bank Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Poland).

According to N.I. Pavlenko, under Catherine "serfdom developed in depth and breadth", which was "an example of a glaring contradiction between the ideas of the Enlightenment and government measures to strengthen the serfdom regime."

During her reign, Catherine gave away more than 800 thousand peasants to landlords and nobles, thus setting a kind of record. For the most part, these were not state peasants, but peasants from the lands acquired during the partitions of Poland, as well as palace peasants. But, for example, the number of assigned (possession) peasants from 1762 to 1796. increased from 210 to 312 thousand people, and these were formally free (state) peasants, but turned into serfs or slaves. Possession peasants of the Ural factories took an active part in Peasant War 1773-1775

At the same time, the position of the monastery peasants was alleviated, who were transferred to the jurisdiction of the College of Economy along with the lands. All their duties were replaced by a cash quitrent, which gave the peasants more independence and developed their economic initiative. As a result, the unrest of the monastery peasants stopped.

The fact that a woman who had no formal rights to this was proclaimed empress gave rise to many contenders for the throne, which overshadowed a significant part of the reign of Catherine II. Yes, only from 1764 to 1773 Seven False Peter III appeared in the country(who claimed that they are nothing more than the "resurrected" Peter III) - A. Aslanbekov, I. Evdokimov, G. Kremnev, P. Chernyshov, G. Ryabov, F. Bogomolov, N. Krestov; the eighth was Emelyan Pugachev. And in 1774-1775. to this list was added the “case of Princess Tarakanova”, who pretended to be the daughter of Elizabeth Petrovna.

During 1762-1764. 3 conspiracies aimed at overthrowing Catherine were uncovered, and two of them were associated with the name of the former Russian Emperor Ivan VI, who at the time of accession to the throne of Catherine II continued to remain alive in custody in the Shlisselburg fortress. The first of them involved 70 officers. The second took place in 1764, when Lieutenant V. Ya. Mirovich, who was on guard duty in the Shlisselburg Fortress, won a part of the garrison over to his side in order to free Ivan. The guards, however, in accordance with the instructions given to them, stabbed the prisoner, and Mirovich himself was arrested and executed.

In 1771, a major plague epidemic occurred in Moscow, complicated by popular unrest in Moscow, called the Plague Riot. The rebels destroyed the Chudov Monastery in the Kremlin. The next day, the crowd took the Donskoy Monastery by storm, killed Archbishop Ambrose, who was hiding in it, and began to smash the quarantine outposts and the houses of the nobility. Troops under the command of G. G. Orlov were sent to suppress the uprising. After three days of fighting, the rebellion was crushed.

In 1773-1775 there was a peasant uprising led by Emelyan Pugachev. It covered the lands of the Yaik army, the Orenburg province, the Urals, the Kama region, Bashkiria, part of Western Siberia, the Middle and Lower Volga regions. During the uprising, the Bashkirs, Tatars, Kazakhs, Ural factory workers and numerous serfs from all provinces where hostilities unfolded joined the Cossacks. After the suppression of the uprising, some liberal reforms were curtailed and conservatism intensified.

In 1772 took place The first section of the Commonwealth. Austria received all of Galicia with districts, Prussia - West Prussia (Pomorye), Russia - the eastern part of Belarus to Minsk (provinces of Vitebsk and Mogilev) and part of the Latvian lands that were previously part of Livonia. The Polish Sejm was forced to agree to the partition and renounce claims to the lost territories: Poland lost 380,000 km² with a population of 4 million people.

Polish nobles and industrialists contributed to the adoption of the Constitution of 1791; the conservative part of the population of the Targowice Confederation turned to Russia for help.

In 1793 took place The second section of the Commonwealth, approved by the Grodno Seimas. Prussia received Gdansk, Torun, Poznan (part of the land along the rivers Warta and Vistula), Russia - Central Belarus with Minsk and New Russia (part of the territory of modern Ukraine).

In March 1794, an uprising began under the leadership of Tadeusz Kosciuszko, whose goals were to restore territorial integrity, sovereignty and the Constitution on May 3, but in the spring of that year it was suppressed by the Russian army under the command of A. V. Suvorov. During the Kosciuszko uprising, the insurgent Poles who seized the Russian embassy in Warsaw discovered documents that had a great public outcry, according to which King Stanislav Poniatowski and a number of members of the Grodno Seim at the time of the approval of the 2nd section of the Commonwealth received money from the Russian government - in In particular, Poniatowski received several thousand ducats.

In 1795 took place The third section of the Commonwealth. Austria received Southern Poland with Luban and Krakow, Prussia - Central Poland with Warsaw, Russia - Lithuania, Courland, Volyn and Western Belarus.

October 13, 1795 - a conference of three powers on the fall of the Polish state, it lost statehood and sovereignty.

An important direction foreign policy Catherine II were also the territories of the Crimea, the Black Sea region and the North Caucasus, which were under Turkish rule.

When the uprising of the Bar Confederation broke out, the Turkish sultan declared war on Russia (Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774), using as a pretext that one of the Russian detachments, pursuing the Poles, entered the territory of the Ottoman Empire. Russian troops defeated the Confederates and began to win one victory after another in the south. Having achieved success in a number of land and sea battles (the Battle of Kozludzhi, the battle of Ryaba Mogila, the battle of Kagul, the battle of Larga, the battle of Chesme, etc.), Russia forced Turkey to sign the Kyuchuk-Kaynardzhy Treaty, as a result of which the Crimean Khanate formally gained independence, but became de facto dependent on Russia. Turkey paid Russia military indemnities in the order of 4.5 million rubles, and also ceded the northern coast of the Black Sea, along with two important ports.

After the end of the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774, Russia's policy towards the Crimean Khanate was aimed at establishing a pro-Russian ruler in it and joining Russia. Under pressure from Russian diplomacy, Shahin Giray was elected khan. The previous khan - protege of Turkey Devlet IV Giray - at the beginning of 1777 tried to resist, but it was suppressed by A. V. Suvorov, Devlet IV fled to Turkey. At the same time, the landing of Turkish troops in the Crimea was prevented, and thus an attempt to unleash new war, after which Turkey recognized Shahin Giray as Khan. In 1782, an uprising broke out against him, which was suppressed by Russian troops brought to the peninsula, and in 1783, by the manifesto of Catherine II, the Crimean Khanate was annexed to Russia.

After the victory, the empress, together with the Austrian emperor Joseph II, made a triumphal trip to the Crimea.

The next war with Turkey took place in 1787-1792 and was an unsuccessful attempt by the Ottoman Empire to regain the lands that had gone to Russia during the Russian-Turkish war of 1768-1774, including Crimea. Here, too, the Russians won a number of important victories, both on land - the Kinburn battle, the Battle of Rymnik, the capture of Ochakov, the capture of Izmail, the battle of Focsani, the Turkish campaigns against Bendery and Ackerman, etc., and the sea ones - the battle of Fidonisi (1788), Battle of Kerch (1790), Battle of Cape Tendra (1790) and Battle of Kaliakria (1791). As a result, the Ottoman Empire in 1791 was forced to sign the Iasi Peace Treaty, which secured the Crimea and Ochakov for Russia, and also moved the border between the two empires to the Dniester.

The wars with Turkey were marked by major military victories by Rumyantsev, Orlov-Chesmensky, Suvorov, Potemkin, Ushakov, and the assertion of Russia in the Black Sea. As a result of them, the Northern Black Sea region, Crimea, and the Kuban region were ceded to Russia, its political positions in the Caucasus and the Balkans were strengthened, and Russia's authority on the world stage was strengthened.

According to many historians, these conquests are the main achievement of the reign of Catherine II. At the same time, a number of historians (K. Valishevsky, V. O. Klyuchevsky, etc.) and contemporaries (Frederick II, French ministers, etc.) explained the “amazing” victories of Russia over Turkey not so much by the strength of the Russian army and navy, which were still rather weak and poorly organized, as a consequence of the extreme decomposition during this period of the Turkish army and state.

Growth of Catherine II: 157 centimeters.

Personal life of Catherine II:

Unlike her predecessor, Catherine did not conduct extensive palace construction for her own needs. For comfortable travel around the country, she arranged a network of small travel palaces along the road from St. Petersburg to Moscow (from Chesmensky to Petrovsky) and only at the end of her life took up the construction of a new country residence in Pella (not preserved). In addition, she was concerned about the lack of a spacious and modern residence in Moscow and its environs. Although she did not visit the old capital often, Catherine for a number of years cherished plans for the restructuring of the Moscow Kremlin, as well as the construction of suburban palaces in Lefortovo, Kolomenskoye and Tsaritsyn. For various reasons, none of these projects was completed.

Catherine was a brunette of medium height. She combined high intelligence, education, statesmanship and commitment to "free love". Catherine is known for her connections with numerous lovers, the number of which (according to the list of the authoritative Ekaterinologist P.I. Bartenev) reaches 23. The most famous of them were Sergey Saltykov, G.G. was the cornet Platon Zubov, who became a general. With Potemkin, according to some sources, Catherine was secretly married (1775, see Wedding of Catherine II and Potemkin). After 1762, she planned a marriage with Orlov, but on the advice of those close to her, she abandoned this idea.

Catherine's love affairs are marked by a series of scandals. So, Grigory Orlov, being her favorite, at the same time (according to M. M. Shcherbatov) cohabited with all her ladies-in-waiting and even with his 13-year-old cousin. The favorite of Empress Lanskoy used an aphrodisiac to increase "male strength" (kontarid) in ever-increasing doses, which, apparently, according to the conclusion of the court physician Weikart, was the cause of his unexpected death at a young age. Her last favorite, Platon Zubov, was a little over 20 years old, while Catherine’s age at that time had already exceeded 60. Historians mention many other scandalous details (“bribe” of 100 thousand rubles paid to Potemkin by the future favorites of the Empress, many of who were previously his adjutants, testing their "male strength" by her ladies-in-waiting, etc.).

The bewilderment of contemporaries, including foreign diplomats, the Austrian emperor Joseph II, etc., caused rave reviews and characteristics that Catherine gave to her young favorites, for the most part devoid of any outstanding talents. As N. I. Pavlenko writes, “neither before Catherine nor after her, debauchery did not reach such a large scale and did not manifest itself in such a frankly defiant form.”

It is worth noting that in Europe Catherine's "debauchery" was not such a rare phenomenon against the background of the general licentiousness of the mores of the 18th century. Most kings (with the possible exception of Frederick the Great, Louis XVI and Charles XII) had numerous mistresses. However, this does not apply to reigning queens and empresses. Thus, the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa wrote about the "disgust and horror" that such persons as Catherine II instill in her, and this attitude towards the latter was shared by her daughter Marie Antoinette. As K. Valishevsky wrote in this regard, comparing Catherine II with Louis XV, “the difference between the sexes until the end of time, we think, will give a deeply unequal character to the same actions, depending on whether they are committed by a man or a woman ... besides, the mistresses of Louis XV never influenced the fate of France.

There are numerous examples of the exceptional influence (both negative and positive) that Catherine's favorites (Orlov, Potemkin, Platon Zubov, etc.) had on the fate of the country, starting from June 28, 1762, until the death of the Empress, as well as on its domestic, foreign policy and even on military operations. According to N.I. Pavlenko, in order to please the favorite Grigory Potemkin, who envied the glory of Field Marshal Rumyantsev, this outstanding commander and hero of the Russian-Turkish wars was removed by Catherine from command of the army and was forced to retire to his estate. Another, very mediocre commander, Musin-Pushkin, on the contrary, continued to lead the army, despite his blunders in military campaigns (for which the empress herself called him a “real blockhead”) - due to the fact that he was a “favorite on June 28”, one of those who helped Catherine seize the throne.

In addition, the institute of favoritism had a negative effect on the morals of the higher nobility, who sought benefits through flattery to a new favorite, tried to make “his own man” into lovers to the empress, etc. A contemporary M. M. Shcherbatov wrote that Catherine’s favoritism and debauchery II contributed to the decline in the morals of the nobility of that era, and historians agree with this.

Catherine had two sons: (1754) and Alexei Bobrinsky (1762 - son of Grigory Orlov), as well as her daughter Anna Petrovna (1757-1759, possibly from the future King of Poland Stanislav Poniatovsky), who died in infancy. Less likely is Catherine's motherhood in relation to Potemkin's pupil named Elizabeth, who was born when the Empress was over 45 years old.

The golden age, the age of Catherine, the Great Kingdom, the heyday of absolutism in Russia - this is how historians designate and designate the reign of Russia by Empress Catherine II (1729-1796)

“Her reign was successful. As a conscientious German, Catherine worked diligently for the country that gave her such a good and profitable position. She naturally saw the happiness of Russia in the greatest possible expansion of the boundaries of the Russian state. By nature, she was smart and cunning, well versed in the intrigues of European diplomacy. Cunning and flexibility were the basis of what in Europe, depending on the circumstances, was called the policy of Northern Semiramis or the crimes of Moscow Messalina. (M. Aldanov "Devil's Bridge")

Years of reign of Russia by Catherine the Great 1762-1796

The real name of Catherine II was Sophia Augusta Frederick of Anhalt-Zerbstsk. She was the daughter of Prince Anhalt-Zerbst, who represented “a side line of one of the eight branches of the Anhalst house,” the commandant of the city of Stettin, which was in Pomerania, an area subject to the kingdom of Prussia (today the Polish city of Szczecin).

“In 1742, the Prussian king Frederick II, wanting to annoy the Saxon court, who expected to marry his princess Maria Anna to the heir to the Russian throne, Peter Karl Ulrich of Holstein, who suddenly became Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, began to hastily look for another bride for the Grand Duke.

The Prussian king had three German princesses in mind for this purpose: two of Hesse-Darmstadt and one of Zerbst. The latter was the most suitable for age, but Friedrich knew nothing about the fifteen-year-old bride herself. They only said that her mother, Johanna-Elizabeth, led a very frivolous lifestyle and that little Fike was hardly really the daughter of the Zerbst prince Christian-August, who served as governor in Stetin ”

How long, short, but in the end, the Russian Empress Elizaveta Petrovna chose the little Fike as a wife for her nephew Karl-Ulrich, who became Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich in Russia, the future Emperor Peter the Third.

Biography of Catherine II. Briefly

- 1729, April 21 (old style) - Catherine II was born

- 1742, December 27 - on the advice of Frederick II, the mother of Princess Fikkhen (Fike) sent a letter to Elizabeth with congratulations for the New Year

- 1743, January - kind letter in return

- 1743, December 21 - Johanna-Elizabeth and Fikchen received a letter from Brumner, the tutor of Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich, with an invitation to come to Russia

“Your Grace,” Brummer wrote pointedly, “are too enlightened not to understand the true meaning of the impatience with which Her Imperial Majesty wishes to see you here as soon as possible, as well as your princess, your daughter, about whom rumor has told us so much good”

- December 21, 1743 - on the same day a letter from Frederick II was received in Zerbst. The Prussian king ... strongly advised to go and keep the trip a strict secret (so that the Saxons would not find out ahead of time)

- 1744, February 3 - German princesses arrived in St. Petersburg

- 1744, February 9 - the future Catherine the Great and her mother arrived in Moscow, where at that moment there was a courtyard

- 1744, February 18 - Johanna-Elizabeth sent a letter to her husband with the news that their daughter was the bride of the future Russian Tsar

- 1745, June 28 - Sophia Augusta Frederica adopted Orthodoxy and the new name Catherine

- 1745, August 21 - marriage and Catherine

- 1754, September 20 - Catherine gave birth to a son, heir to the throne of Paul

- 1757, December 9 - Catherine had a daughter, Anna, who died 3 months later

- 1761, December 25 - Elizaveta Petrovna died. Peter III became king

“Peter the Third was the son of the daughter of Peter I and the grandson of the sister of Charles XII. Elizabeth, having ascended the Russian throne and wishing to secure it beyond her father's line, sent Major Korf on a mission to take her nephew from Kiel at all costs and bring him to Petersburg. Here the Duke of Holstein, Karl-Peter-Ulrich, was transformed into Grand Duke Peter Fedorovich and forced to study the Russian language and the Orthodox catechism. But nature was not as favorable to him as fate .... He was born and grew up as a frail child, poorly endowed with abilities. Early becoming an orphan, Peter in Holstein received a worthless upbringing under the guidance of an ignorant courtier.

Humiliated and embarrassed in everything, he acquired bad tastes and habits, became irritable, quarrelsome, stubborn and false, acquired a sad tendency to lie ...., and in Russia he also learned to get drunk. In Holstein, he was taught so badly that he came to Russia as a 14-year-old ignoramus and even struck Empress Elizabeth with his ignorance. The rapid change of circumstances and educational programs completely confused his already fragile head. Forced to study this and that without connection and order, Peter ended up learning nothing, and the dissimilarity between the Holstein and Russian situation, the senselessness of Kiel and St. Petersburg impressions completely weaned him from understanding his surroundings. ... He was fond of military glory and the strategic genius of Frederick II ... " (V. O. Klyuchevsky "Course of Russian History")

- April 13, 1762 - Peter made peace with Frederick. All the lands captured by Russia from Prussia in the course were returned to the Germans

- 1762, May 29 - the union treaty of Prussia and Russia. Russian troops were placed at the disposal of Frederick, which caused sharp discontent among the guards.

(The flag of the guard) “became the empress. The emperor lived badly with his wife, threatened to divorce her and even imprison her in a monastery, and put in her place a person close to him, the niece of Chancellor Count Vorontsov. Catherine kept aloof for a long time, patiently enduring her position and not entering into direct relations with the dissatisfied. (Klyuchevsky)

- 1762, June 9 - at a ceremonial dinner on the occasion of the confirmation of this peace treaty, the emperor proclaimed a toast to the imperial family. Ekaterina drank her glass while sitting. When asked by Peter why she did not get up, she replied that she did not consider it necessary, since the imperial family consists entirely of the emperor, of herself and their son, the heir to the throne. “And my uncles, the Holstein princes?” - Peter objected and ordered Adjutant General Gudovich, who was standing behind his chair, to approach Catherine and say an abusive word to her. But, fearing that Gudovich would soften this impolite word during the transmission, Pyotr himself shouted it across the table aloud.

The Empress wept. On the same evening she was ordered to arrest her, which, however, was not carried out at the request of one of Peter's uncles, the unwitting culprits of this scene. Since that time, Catherine began to listen more carefully to the proposals of her friends, which were made to her, starting from the very death of Elizabeth. The enterprise was sympathized with many persons of high Petersburg society, for the most part personally offended by Peter

- 1762, June 28 -. Catherine is proclaimed empress

- 1762, June 29 - Peter the Third abdicated

- 1762, July 6 - killed in prison

- 1762, September 2 - Coronation of Catherine II in Moscow

- 1787, January 2-July 1 -

- 1796, November 6 - death of Catherine the Great

Domestic policy of Catherine II

-

Change in central government: in 1763 streamlining the structure and powers of the Senate

-

Liquidation of the autonomy of Ukraine: liquidation of the hetmanate (1764), liquidation of the Zaporozhian Sich (1775), serfdom of the peasantry (1783)

-

Further subordination of the church to the state: secularization of church and monastery lands, 900 thousand church serfs became state serfs (1764)

-

Improving legislation: a decree on tolerance for schismatics (1764), the right of landlords to exile peasants to hard labor (1765), the introduction of a noble monopoly on distillation (1765), a ban on peasants to file complaints against landowners (1768), the creation of separate courts for nobles, townspeople and peasants (1775), etc.

-

Improving the administrative system of Russia: the division of Russia into 50 provinces instead of 20, the division of provinces into districts, the division of power in the provinces by function (administrative, judicial, financial) (1775);

-

Strengthening the position of the nobility (1785):

- confirmation of all class rights and privileges of the nobility: exemption from compulsory service, from poll tax, corporal punishment; the right to unlimited disposal of the estate and land together with the peasants;

- the creation of noble class institutions: county and provincial noble assemblies, which met every three years and elected county and provincial marshals of the nobility;

- conferring the title of "noble" on the nobility.

“Catherine II was well aware that she could stay on the throne, only in every possible way pleasing the nobility and officers, in order to prevent or at least reduce the danger of a new palace conspiracy. This is what Catherine did. Her whole internal policy was to ensure that the life of officers at her court and in the guards was as profitable and pleasant as possible.

- Economic innovations: the establishment of a financial commission for the unification of money; establishment of a commission on commerce (1763); a manifesto on the conduct of a general demarcation to fix land plots; the establishment of the Free Economic Society to help noble entrepreneurship (1765); financial reform: the introduction of paper money - bank notes (1769), the creation of two bank notes (1768), the issuance of the first Russian external loan (1769); establishment of a postal department (1781); permission to start printing houses for private individuals (1783)

Foreign policy of Catherine II

- 1764 - Treaty with Prussia

- 1768-1774 - Russian-Turkish war

- 1778 - Restoration of the alliance with Prussia

- 1780 - Union of Russia, Denmark. and Sweden to protect navigation during the American War of Independence

- 1780 - Defensive alliance of Russia and Austria

- 1783, April 8 -

- 1783, August 4 - the establishment of a Russian protectorate over Georgia

- 1787-1791 —

- 1786, December 31 - trade agreement with France

- 1788 June - August - war with Sweden

- 1792 - rupture of relations with France

- 1793, March 14 - treaty of friendship with England

- 1772, 1193, 1795 - participation together with Prussia and Austria in the partitions of Poland

- 1796 - war in Persia in response to the Persian invasion of Georgia

Personal life of Catherine II. Briefly

“Catherine, by nature, was neither evil nor cruel ... and excessively power-hungry: all her life she was invariably under the influence of successive favorites, to whom she gladly ceded her power, interfering in their orders with the country only when they showed theirs very clearly. inexperience, inability or stupidity: she was smarter and more experienced in business than all her lovers, with the exception of Prince Potemkin.

There was nothing excessive in Catherine's nature, except for a strange mixture of the most rude and ever-increasing sensuality over the years with purely German, practical sentimentality. At sixty-five, she fell in love like a girl with twenty-year-old officers and sincerely believed that they were also in love with her. In her seventies, she cried bitter tears when it seemed to her that Platon Zubov was more restrained with her than usual.(Mark Aldanov)

At birth, the girl was given the name Sophia Frederica Augusta. Her father, Christian August, was the prince of the small German principality of Anhalt-Zerbst, but he won fame for his achievements in the military field. The mother of the future Catherine, Princess of Holstein-Gottorp Johanna Elizabeth, cared little about raising her daughter. And because the girl was raised by a governess.

Catherine was educated by tutors, and, among them, a chaplain who gave the girl religious lessons. However, the girl had her own point of view on many questions. She also mastered three languages: German, French and Russian.

Entry into the royal family of Russia

In 1744, the girl goes with her mother to Russia. The German princess becomes engaged to Grand Duke Peter and converts to Orthodoxy, receiving the name Catherine at baptism.

August 21, 1745 Catherine marries the heir to the throne of Russia, becoming a princess. However, family life was far from happy.

After long childless years, Catherine II finally gave birth to an heir. Her son Pavel was born on September 20, 1754. And then heated debate flared up about who really is the boy's father. Be that as it may, Catherine hardly saw her first-born: shortly after birth, Empress Elizabeth takes the child to be raised.

Seizure of the throne

On December 25, 1761, after the death of Empress Elizabeth, Peter III ascended the throne, and Catherine became the wife of the emperor. However, it has little to do with state affairs. Peter and his wife were frankly cruel. Soon, due to the stubborn support he provided to Prussia, Peter becomes a stranger to many court, secular and military officials. The founder of what today we call progressive internal state reforms, Peter also quarreled with the Orthodox Church, taking away church lands. And now, six months later, Peter was deposed from the throne as a result of a conspiracy that Catherine entered into with her lover, Russian lieutenant Grigory Orlov, and a number of other persons, in order to seize power. She successfully manages to force her husband to abdicate and take control of the empire into her own hands. A few days after the abdication, in one of his estates, in Ropsha, Peter was strangled. What role Catherine played in the murder of her husband is unclear to this day.

Fearing herself to be thrown off by the opposing forces, Catherine is trying with all her might to win the favor of the troops and the church. She recalls the troops sent by Peter to the war against Denmark and in every possible way encourages and gives gifts to those who go over to her side. She even compares herself to Peter the Great, whom she reveres, declaring that she is following in his footsteps.

Governing body

Despite the fact that Catherine is a supporter of absolutism, she still makes a number of attempts to carry out social and political reforms. She publishes a document, the "Order", in which she proposes to abolish the death penalty and torture, and also proclaims the equality of all people. However, the Senate resolutely refuses any attempts to change the feudal system.

After finishing work on the "Order", in 1767, Catherine convenes representatives of various social and economic strata of the population to form the Legislative Commission. The commission did not leave the legislative body, but its convocation went down in history as the first time that representatives of the Russian people from all over the empire had the opportunity to express their ideas about the needs and problems of the country.

Later, in 1785, Catherine issued the Charter of the Nobility, in which she radically changed politics and challenged the power of the upper classes, in which most of the masses were under the yoke of serfdom.

Catherine, a religious skeptic by nature, seeks to subjugate Orthodox Church. At the beginning of her reign, she returned land and property to the church, but soon changed her views. The empress declares the church a part of the state, and therefore all her possessions, including more than a million serfs, become the property of the empire and are subject to taxes.

Foreign policy

During her reign, Catherine expands the borders of the Russian Empire. She makes significant acquisitions in Poland, having previously seated her former lover, the Polish prince Stanislaw Poniatowski, on the throne of the kingdom. Under the agreement of 1772, Catherine gives part of the lands of the Commonwealth to Prussia and Austria, while the eastern part of the kingdom, where many Russian Orthodox live, goes to the Russian Empire.

But such actions cause extreme disapproval of Turkey. In 1774, Catherine makes peace with the Ottoman Empire, according to which the Russian state receives new lands and access to the Black Sea. One of the heroes of the Russian-Turkish war was Grigory Potemkin, a reliable adviser and lover of Catherine.

Potemkin, a loyal supporter of the policy of the empress, himself proved himself to be an outstanding statesman. It was he, in 1783, who convinced Catherine to annex the Crimea to the empire, thereby strengthening her position on the Black Sea.

Love for education and art

At the time of Catherine's accession to the throne, Russia for Europe was a backward and provincial state. The Empress is trying with all her might to change this opinion, expanding the possibilities for new ideas in education and the arts. In St. Petersburg, she establishes a boarding school for girls of noble birth, and later free schools open in all cities of Russia.

Catherine patronizes many cultural projects. She is gaining fame as an ardent collector of art, and most of her collection is exhibited in her residence in St. Petersburg, in the Hermitage.

Catherine, passionately fond of literature, is especially favorable to the philosophers and writers of the Enlightenment. Endowed with literary talent, the empress describes her own life in a collection of memoirs.

Personal life

The love life of Catherine II became the subject of many gossip and false facts. The myths about her insatiability have been debunked, but this royal person really had many love affairs in her life. She could not remarry, because marriage could shake her position, and therefore in society she had to wear a mask of chastity. But, far from prying eyes, Catherine showed a remarkable interest in men.

End of reign

By 1796, Catherine had absolute power in the empire for several decades. And in last years During her reign, she showed all the same vivacity of mind and strength of spirit. But in mid-November 1796, she was found unconscious on the bathroom floor. At that time, everyone came to the conclusion that she had a stroke. 4.2 points. Total ratings received: 100.

Doctor historical sciences M. RAKHMATULLIN.

During the long decades of the Soviet era, the history of the reign of Catherine II was presented with a clear bias, and the image of the Empress herself was deliberately distorted. From the pages of a few publications, a cunning and conceited German princess appears, who treacherously seized the Russian throne and is most concerned with satisfying her sensual desires. Such judgments are based either on a frankly politicized motive, or purely emotional memories of her contemporaries, or, finally, the tendentious intent of her enemies (especially from among foreign opponents), who tried to discredit the empress's tough and consistent upholding of Russia's national interests. But Voltaire, in one of his letters to Catherine II, called her "Northern Babylon", likening the heroine of Greek mythology, whose name is associated with the creation of one of the seven wonders of the world - hanging gardens. Thus, the great philosopher expressed his admiration for the activities of the Empress in the transformation of Russia, her wise rule. In the proposed essay, an attempt was made to impartially tell about the affairs and personality of Catherine II. "I did my job pretty well"

Crowned Catherine II in all the splendor of her coronation attire. The coronation traditionally took place in Moscow on September 22, 1762.

Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, who reigned from 1741 to 1761. Portrait of the middle of the XVIII century.

Peter I married his eldest daughter Tsesarevna Anna Petrovna to the Duke of Holstein Karl-Friedrich. Their son became the heir to the Russian throne, Peter Fedorovich.

Catherine II's mother, Johanna-Elizabeth of Anhalt-Zerbst, who secretly tried to intrigue in favor of the Prussian king, secretly from Russia.

The Prussian King Frederick II, whom the young Russian heir tried to imitate in everything.

Science and life // Illustrations

Grand Duchess Ekaterina Alekseevna and Grand Duke Pyotr Fedorovich. Their marriage turned out to be extremely unsuccessful.

Count Grigory Orlov is one of the active organizers and executors of the palace coup that elevated Catherine to the throne.

The most ardent part in the coup of June 1762 was taken by the still very young Princess Ekaterina Romanovna Dashkova.

Family portrait of the royal couple, made shortly after the accession to the throne of Peter III. Next to his parents is the young heir Pavel in oriental costume.

The Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, where dignitaries and nobles took the oath to Empress Catherine II.

The future Russian Empress Catherine II Alekseevna, nee Sophia Frederick Augusta, Princess of Anhaltzerbst, was born on April 21 (May 2), 1729 in Stettin (Prussia), which was provincial at that time. Her father, the unremarkable Prince Christian-August, made a good career by devoted service to the Prussian king: regiment commander, commandant of Stettin, governor. In 1727 (he was then 42 years old) he married the 16-year-old Holstein-Gottorp princess Johanna-Elisabeth.

The somewhat eccentric princess, who had an irrepressible addiction to entertainment and short trips to numerous and, unlike her, rich relatives, put family concerns in the first place. Among the five children, the first-born daughter Fikkhen (that was the name of all the family Sophia Frederic) was not her favorite - they were waiting for a son. “My birth was not particularly joyfully welcomed,” Catherine later wrote in her Notes. The power-hungry and strict parent, out of a desire to "knock out her pride," often rewarded her daughter with slaps in the face for innocent childish pranks and for unchildish stubbornness of character. Little Fikkhen found comfort in a good-natured father. Constantly employed in the service and practically not interfering in the upbringing of children, he nevertheless became for them an example of conscientious service in the state field. “I have never met a more honest person, both in terms of principles and in relation to actions,” Catherine will say about her father at a time when she already knew people well.

Lack of material resources prevented parents from hiring expensive, experienced teachers and governesses. And here fate generously smiled on Sophia Frederica. After the change of several careless governesses, the French emigrant Elisabeth Kardel (nicknamed Babet) became her good mentor. As Catherine II later wrote about her, she "knew almost everything, having learned nothing; she knew all comedies and tragedies like the back of her hand and was very funny." The heartfelt response of the pupil draws Babet "an example of virtue and prudence - she had a naturally elevated soul, a developed mind, an excellent heart; she was patient, meek, cheerful, fair, constant."

Perhaps the main merit of the clever Kardel, who had an exceptionally balanced character, can be called the fact that she attracted the stubborn and secretive at first (the fruits of her previous upbringing) Fikkhen to reading, in which the capricious and wayward princess found true pleasure. A natural consequence of this passion is the soon-to-be developed interest of a girl developed beyond her years in serious works of a philosophical content. It is no coincidence that already in 1744 one of the enlightened friends of the family, the Swedish Count Gyllenborg, jokingly, but not without reason, called Fikchen "a fifteen-year-old philosopher." It is curious that Catherine II herself admitted that the acquisition of "intelligence and virtues" was greatly facilitated by the conviction inspired by her mother, "as if I were completely ugly," which kept the princess from empty social entertainment. Meanwhile, one of her contemporaries recalls: “She was perfectly built, from infancy she was distinguished by a noble posture and was taller than her years. Her facial expression was not beautiful, but very pleasant, and her open look and kind smile made her whole figure very attractive.”

However, the further fate of Sophia (as well as many later German princesses) was determined not by her personal merits, but by the dynastic situation in Russia. The childless Empress Elizaveta Petrovna, immediately after her accession, began to look for an heir worthy of the Russian throne. The choice fell on the only direct successor of the family of Peter the Great, his grandson - Karl Peter Ulrich. The son of the eldest daughter of Peter I Anna and the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, Karl Friedrich, was left an orphan at the age of 11. The upbringing of the prince was carried out by pedantic German teachers, led by the pathologically cruel Chamber Marshal Count Otto von Brummer. The ducal offspring, frail from birth, was sometimes kept half-starved, and for any offense they were forced to kneel on peas for hours, often and painfully flogged. “I order you to be whipped so,” Brummer shouted, “that the dogs will lick the blood.” The boy found an outlet in his passion for music, addicted to the pathetically sounding violin. Another passion of his was playing with tin soldiers.

The humiliations to which he was subjected from day to day gave their results: the prince, as contemporaries note, became "hot-tempered, false, loved to brag, learned to lie." He grew up a cowardly, secretive, capricious beyond measure and thought a lot about himself. Here is a laconic portrait of Peter Ulrich, drawn by our brilliant historian V.O. Klyuchevsky: “His way of thinking and acting gave the impression of something surprisingly unthought-out and unfinished. He looked at serious things with a childish look, and treated children’s undertakings with the seriousness of a mature husband. He was like a child who imagined himself to be an adult; in fact, he was an adult who forever remained a child.