East. The indigenous peoples of Siberia: Evenki, Khanty, Mansi, Yakuts, Chukchi, and others were engaged in cattle breeding, hunting, fishing, tribal relations dominated among them. The accession of Western Siberia took place in the late 16th century - the conquest of the Siberian Khanate. Gradually, explorers and industrialists penetrate Siberia, followed by representatives of the tsarist government. Settlements and fortresses are founded.

Ostrogs - Yenisei (1618), Ilimsk (1630), Irkutsk (1652), Krasnoyarsk (1628). The Siberian order is created, Siberia is divided into 19 districts, controlled by governors from Moscow.

Pioneers: Semyon Dezhnev, 1648 - discovered the strait separating Asia from North America. Vasily Poyarkov, 1643-1646 - at the head of the Cossacks sailed along the rivers Lena, Aldan, along the Amur to the Sea of \u200b\u200bOkhotsk. Erofey Khabarov, in 1649 carried out a campaign in Dauria, compiled maps of the lands along the Amur. Vladimir Atlasov, in 1696 - an expedition to Kamchatka.

Annexation of Western Siberia (subjugation of the Siberian Khanate at the end of the 16th century)

Penetration into Siberia of explorers and industrialists, as well as representatives of the tsarist government (in the 17th century

Foundation of settlements and fortresses:

Yenisei jail (1618)

Krasnoyarsk prison (1628)

Ilim prison (1630)

Yakut prison (1632)

Irkutsk jail (1652)

Selenginsky prison (1665)

Creation of the Siberian order. The division of Siberia into 19 counties, which were ruled by governors appointed from Moscow ( 1637 )

Russian pioneers of Siberia

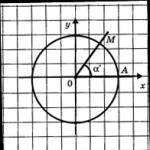

Semyon Dezhnev (1605-1673)- made a major geographical discovery: in 1648 he sailed along the Chukchi Peninsula and discovered the strait separating Asia from North America

Vasily Poyarkov in 1643-1646 at the head of a detachment of Cossacks, he went from Yakutsk along the Lena and Aldan rivers, went along the Amur to the Sea of \u200b\u200bOkhotsk, and then returned to Yakutsk

Erofei Khabarov (1610-1667)- in 1649-1650. carried out a trip to Dauria, mastered the lands along the Amur River and compiled their maps (drawing)

Vladimir Atlasov in 1696-1697 undertook an expedition to Kamchatka, as a result of which it was annexed to Russia

The inclusion of the "Siberian kingdom" in the Russian state

Since state revenues have declined catastrophically, the problem of replenishing the state treasury, among the mass of urgent matters, was one of the most urgent and painful. In solving this main problem, like others, the Russian state saved the diversity and vastness of its geopolitical foundation - the Eurasian scale of the Muscovite Empire.

Having ceded its western provinces to Poland and Sweden and having suffered heavy losses in the west, Russia turned for new forces: to its eastern possessions - the Urals, Bashkiria and Siberia.

On May 24, 1613, the tsar wrote a letter to the Stroganovs, in which he described the desperate state of the country: the treasury was empty, and asked to save the fatherland.

The Stroganovs did not reject the request, and this was the beginning of their significant assistance to the government of Tsar Michael.

The natural result of the conquest of Kazan was the Russian advance into Bashkiria. In 1586, the Russians built the Ufa fortress in the heart of Bashkiria.

The Russian administration did not interfere in the tribal organization and affairs of the Bashkir clans, as well as in their traditions and habits, but demanded regular payment of yasak (tribute paid in furs). This was the main source of income for Russians in Bashkiria. Yasak was also the financial basis of the Russian administration of Siberia.

By 1605, the Russians had established firm control over Siberia. The city of Tobolsk in the lower reaches of the Irtysh River became the main fortress and administrative capital of Siberia. In the north, Mangazeya on the Taz River (which flows into the Gulf of Ob) quickly turned into an important center for the fur trade. In the southeast of Western Siberia, the Tomsk fortress on the tributary of the middle Ob served as the advanced post of the Russians on the border of the Mongol-Kalmyk world.

In 1606-1608, however, there were unrest of the Samoyeds (Nenets), Ostyaks, Selkups (Narym Ostyaks) and the Yenisei Kirghiz, the direct cause of which was the case of a flagrant violation of the principles of Russian rule in Siberia - shameful abuses and extortion in relation to the indigenous inhabitants of sides of two Moscow heads (captains) sent to Tomsk by Tsar Vasily Shuisky in 1606

Attempts by the rebels to storm Tobolsk and some other Russian fortresses failed, and the unrest was suppressed with the help of the Siberian Tatars, some of whom were attacked by the rebels. During 1609 and 1610 The Ostyaks continued to oppose Russian rule, but their rebellious spirit gradually weakened.

The king became the patron of three khans, one Mongol and two Kalmyk, who were in hostile relations. The king was supposed to be the judge, but none of his nominal vassals made concessions to the other two, and the king did not have sufficient troops to force peace between them.

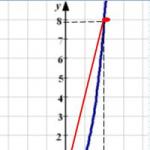

By 1631, one Cossack gang reached Lake Baikal, and the other two - to the Lena River. In 1632 the city of Yakutsk was founded. In 1636, a group of Cossacks, sailing from the mouth of the Olenyok River, entered the Arctic Ocean and went east along the coast. In the footsteps of this and other expeditions, the Cossack Semyon Dezhnev sailed around the northeastern tip of Asia. Having started his journey at the mouth of the Kolyma River, he then ended up in the Arctic Ocean and landed at the mouth of the Anadyr River in the Bering Sea (1648-1649).

Ten years before Dezhnev's Arctic voyage, a Cossack expedition from Yakutsk managed to enter the Sea of Okhotsk along the Aldan River. In the 1640s and 1650s the lands around Lake Baikal were explored. In 1652 founded Irkutsk. In the east, Poyarkov descended the lower reaches of the Amur River and from its mouth sailed north along the coast of the Sea of Okhotsk (1644-1645). In 1649‑1650. Erofey Khabarov opened the way for the Russians to the middle Amur.

Thus, by the middle of the seventeenth century, the Russians had established their control over all of Siberia except for the Kamchatka Peninsula, which they annexed at the end of the century (1697-1698).

As for the ethnic composition of the newly annexed areas, most of the vast territory between the Yenisei and the Sea of Okhotsk was inhabited by Tungus tribes. The Tungus, linguistically related to the Manchus, were engaged in hunting and reindeer herding. There were about thirty thousand of them.

Around Lake Baikal there were several settlements of the Buryats (a branch of the eastern Mongols) with a population of at least twenty-six thousand people. The Buryats were mainly cattle breeders and hunters, some of them were engaged in agriculture.

The Yakuts lived in the basin of the Middle Lena. They linguistically belonged to the Turkic family of peoples. There were about twenty-five thousand of them - mostly cattle breeders, hunters and fishermen.

In the northeastern triangle of Siberia, between the Arctic Ocean and the northern part of the Pacific Ocean, various Paleo-Asian tribes lived, about twenty-five thousand reindeer herders and fishermen

Indigenous peoples were much more numerous than Russian newcomers, but they were disunited and did not have firearms. Clan and tribal elders often clashed with each other. Most of them were ready to recognize the king as their sovereign and pay him yasak.

In 1625 in Siberia there were fourteen cities and forts (fortresses), where governors were appointed. These were Tobolsk, Verkhoturye, Tyumen, Turinsk, Tara, Tomsk, Berezov, Mangazeya, Pelym, Surgut, Kets Ostrog, Kuznetsk, Narym and Yeniseisk. Two governors were usually appointed to each city, one of which was the eldest; in each prison - one. With further advancement to the east, the number of cities and forts, and consequently, the governor increased.

Each voivode supervised the military and civil affairs of his district. He reported directly to Moscow, but the Tobolsk governor had a certain amount of power over all the others, which allowed him to coordinate the actions of the Siberian armed forces and government agencies. The senior voivode of Tobolsk also had a limited right to maintain (under Moscow's control) relations with neighboring peoples such as the Kalmyks and the Eastern Mongols.

The position of the governor in Muscovy, and even more so in Siberia, provided a lot of opportunities for enrichment, but the remoteness, difficulties of travel and unsafe living conditions in the border areas frightened off the Moscow court aristocracy. In order to attract famous boyars to serve in Siberia, the Moscow government granted the Siberian governors the status that governors had in the active army, which meant better salaries and special privileges. For the period of service in Siberia, the voivode's possessions in Muscovy were exempt from taxes. His serfs and serfs were not subject to prosecution, except in cases of robbery. All legal cases against them were postponed until the return of the owner. Each governor was provided with all the necessary means for travel to Siberia and back.

The Russian armed forces in Siberia consisted of boyar children; foreigners such as prisoners of war, settlers and mercenaries sent to Siberia as punishment (they were all called "ditva" because most of them were Lithuanians and Western Russians); archers and Cossacks. In addition to them, there were local auxiliary troops (in Western Siberia, mostly Tatar). According to Lantsev's calculations in 1625. in Siberia there were less than three thousand Moscow soldiers, less than a thousand Cossacks and about one thousand locals. Ten years later, the corresponding figures were as follows: five thousand, two thousand, and about two thousand. Parallel to the growth of the armed forces in Siberia, there was a gradual expansion of agricultural activities. As noted earlier, the government recruited future Siberian peasants either under a contract (by instrument) or by order (by decree). Peasants mainly moved from the Perm region and the Russian North (Pomorye). The government used a significant number of criminals and exiled prisoners of war for agricultural work. It is estimated that by 1645 at least eight thousand peasant families were settled in Western Siberia. In addition, from 1614 to 1624. more than five hundred exiles were stationed there.

From the very beginning of the Russian advance into Siberia, the government was faced with the problem of a shortage of grain, since before the arrival of the Russians, the agricultural production of the indigenous peoples in western Siberia corresponded only to their own needs. To satisfy the needs of military garrisons and Russian employees, grain had to be brought from Russia.

During the construction of each new city in Siberia, all the land around it suitable for arable land was explored and the best plots were allotted for the sovereign's arable land. The other part was provided to employees and the clergy. The rest could be occupied by peasants. At first, the users of this land were exempted from special duties in favor of the state, but during his tenure as governor of Tobolsk, Suleshev ordered that every tenth sheaf from the harvest on the estates allocated to service people be transferred to the state storage of this city. This legislative act was applied throughout Siberia and remained in force until the end of the 17th century. This order was similar to the institution of tithe arable land (a tenth of the cultivated field) in the southern border regions of Muscovy. Thanks to such efforts, by 1656 there was an abundance of grain in Verkhoturye and, possibly, in some other regions of Western Siberia. In Northern Siberia and Eastern Siberia, the Russians were forced to depend on the import of grain from its western part.

The Russians were interested not only in the development of agriculture in Siberia, but also in the exploration of mineral deposits there. Soon after the construction of the city of Kuznetsk in 1618, local authorities learned from the indigenous people about the existence of iron ore deposits in this area. Four years later, the Tomsk governor sent the blacksmith Fyodor Yeremeev to look for iron ore between Tomsk and Kuznetsk. Eremeev discovered a deposit three miles from Tomsk and brought samples of the ore to Tomsk, where he smelted the metal, the quality of which turned out to be good. The governor sent Eremeev with samples of ore and iron to Moscow, where the experiment was successfully repeated. “And the iron turned out good, and steel could be made from it.” The tsar rewarded Yeremeev and sent him back to Tomsk (1623).

Then two experienced blacksmiths were sent to Tomsk from Ustyuzhna to manage a new foundry for the production of guns. The foundry was small, with a capacity of only one pood of metal per week. However, it served its purpose for a while.

In 1628, iron ore deposits were explored in the Verkhoturye region, several foundries were opened there, the total productive capacity of which was greater and the cost of production was lower than in Tomsk. The foundry in Tomsk was closed, and Verkhoturye became the main Russian metallurgical center of Siberia at that time. In addition to weapons, agricultural and mining tools were produced there.

In 1654, iron ore deposits were discovered on the banks of the Yenisei, five versts from Krasnoyarsk. Copper, tin, lead, silver and gold were also searched in Siberia, but the results appeared at the end of the 17th century.

The income from furs in 1635, as calculated by Milyukov on the basis of official records, amounted to 63,518 rubles. By 1644, it had grown to 102,021 rubles, and by 1655, to 125,000 rubles.

It should be noted that the purchasing power of the Russian ruble in the 17th century was equal to approximately seventeen gold rubles of 1913. Thus, 125,000 rubles of the 17th century can be considered equal to 2,125,000 rubles of 1913.

slide 1

RUSSIAN TRAVELERS AND PIONEERS IN THE 17TH CENTURY

MBOU "Lyceum No. 12", Novosibirsk teacher VKK Stadnichuk T.M.

slide 2

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

If European travelers in the XV-XVII centuries. first of all, they mastered the lands in the west, then the Russian explorers went to the east - beyond the Ural Mountains to the expanses of Siberia. Cossacks went there, recruited from the townspeople and "free walking people" from the northern cities.

slide 3

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

For fur riches and walrus tusks, hunters-"industrialists" went. Merchants brought to these lands the goods needed by service people and natives - flour, salt, cloth, copper boilers, pewter utensils, axes, needles - a profit of 30 rubles per ruble invested. Black-skinned peasants and artisans-blacksmiths were transferred to Siberia, and criminals and foreign prisoners of war began to be exiled there. Aspired to new lands and free settlers.

slide 4

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

The pioneers were desperately courageous, enterprising, resolute people. In the footsteps of Yermak, new detachments of Cossacks and service people came. The governors sent to Siberia founded the first cities: on the Tura - Tyumen, on the Ob and its tributaries - Berezov, Surgut; in 1587, the Siberian capital, Tobolsk, was founded on the Irtysh.

TOBOLSK KREMLIN

slide 5

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

In 1598, a detachment of governor Andrei Voeikov defeated the army of Khan Kuchum in the Baraba steppe. Kuchum fled and died in 1601, but his sons continued to raid Russian possessions for several more years.

slide 6

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

In 1597, the townsman Artemy Babinov paved the overland route from Solikamsk through the Ural Mountains. The gates of Siberia was the Verkhoturye fortress. The road became the main route connecting the European part of Russia with Asia. As a reward, Babinov received a royal charter for the management of this road and exemption from taxes.

Slide 7

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

The sea route to Siberia ran along the coast of the Arctic Ocean from Arkhangelsk to the shores of the Yamal Peninsula.

Not far from the Arctic Circle, on the river Taz, which flows into the Gulf of Ob, Mangazeya was founded in 1601.

Slide 8

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

Creating strongholds, explorers went further east along the great Siberian rivers and their tributaries. So Tomsk and Kuznetsk prison appeared on the Tom, Turukhansk, Yeniseisk and Krasnoyarsk appeared on the Yenisei.

TOMSKY OSTROG 1604

Slide 9

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

Streltsy centurion Pyotr Beketov in 1632 founded Yakutsk on the Lena - the base for the exploration and development of Eastern Siberia. In 1639, from the upper reaches of the Aldan tributary of the Lena, 30 people, led by Ivan Moskvitin, were the first Russians to reach the Pacific coast, and a few years later the Russian port of Okhotsk prison was built there.

YAKUTSKY OSTROG

Slide 10

WHO WENT TO SIBERIA AND HOW?

In 1641, the Cossack foreman Mikhail Stadukhin, having equipped a detachment at his own expense, went to the mouth of the Indigirka, sailed to the Kolyma by sea and set up a prison there. The local population (Khanty, Mansi, Evenki, Yakuts) passed "under the sovereign's hand" and had to pay yasak with "precious furs."

slide 11

SEMEN DEZHNEV

Semyon Ivanovich Dezhnev, among other "free" people, contracted to serve in Siberia, served first in Yeniseisk, then in Yakutsk, went on long-distance expeditions for yasak to Indigirka and Kolyma.

slide 12

SEMEN DEZHNEV

Dezhnev, as a representative of state power, went on a sea expedition of the Kholmogory merchant Fedot Popov. In June 1648, 90 people on koch ships left the mouth of the Kolyma. The extreme northeastern tip of Asia (later called Cape Dezhnev) was rounded by only two ships.

slide 13

SEMEN DEZHNEV

Koch Dezhnev was thrown onto a deserted coast south of the Anadyr River, where the pioneer and his companions spent a difficult winter. The survivors in the spring of 1649 went up the river and founded the Anadyr prison. After this expedition, Dezhnev served in the Anadyr prison for another ten years.

The strait he passed between Asia and America was indicated on the Russian map of Siberia - "Drawing of the Siberian Land" of 1667, but by the end of the 17th century. the discovery was forgotten: too seldom did the turbulent sea let ships through.

Slide 14

TRIPS TO THE FAR EAST

In the south of Yakutsk, on the Angara, Bratsk and Irkutsk prisons were set up. In 1643, the Cossack Pentecostal Kurbat Ivanov went to Baikal. In Transbaikalia, Chita, Udinsky prison (now Ulan-Ude) and Nerchinsk were founded. The Baikal Buryats agreed to accept Russian citizenship because of the danger of Mongol raids.

slide 15

TRIPS TO THE FAR EAST

Nobleman Vasily Poyarkov in 1643-1646 led the first campaign of the Yakut servicemen and "eager people" to the Amur. With a detachment of 132 people, he went along the Zeya River to the Amur, went down to the sea along it, walked along the southwestern shores of the Sea of \u200b\u200bOkhotsk to the mouth of the Ulya, from where he returned to Yakutsk along the route of I. Moskvitin, collecting information about nature and the peoples living along the Amur - Daurakh, Ducherakh, Nanais, urged them to join Russia.

slide 16

TRIPS TO THE FAR EAST

Entrepreneurial peasant merchant Yerofey Khabarov gathered and equipped about 200 people for a trip to the Amur. In 1649-1653. he twice visited the Amur: with a fight he took the fortified "towns" of the Daurs and Nanais, imposed tribute on them, suppressing resistance attempts. Khabarov compiled the "Drawing of the Amur River" and laid the foundation for the settlement of this territory by Russian people.

Slide 17

TRIPS TO THE FAR EAST

In the spring of 1697, 120 people, led by the Cossack Pentecostal Vladimir Atlasov, went to Kamchatka from the Anadyr prison on reindeer. For three years, Atlasov traveled hundreds of kilometers, founded the Verkhnekamchatsky prison in the center of the peninsula, and returned to Yakutsk with yasak and the first information about Japan.

Slide 18

DEVELOPMENT OF SIBERIA

Mangazeya

Anadyr

Krasnoyarsk

Tomsk

Tobolsk

Tyumen

Surgut

Okhotsk

Yakutsk

Albazin

Nerchinsk

Irkutsk

Slide 19

DEVELOPMENT OF SIBERIA

PIONEERS OF DISCOVERY

Semyon Dezhnev in 1648 made a major geographical discovery: in 1648 he sailed along the Chukchi Peninsula and discovered the strait separating Asia from North America

Vasily Poyarkov 1643-1646 at the head of a detachment of Cossacks, he went from Yakutsk along the Lena and Aldan rivers, went along the Amur to the Sea of \u200b\u200bOkhotsk, and then returned to Yakutsk

Erofey Khabarov 1649-1650 Carried out a trip to Dauria, mastered the lands along the Amur River and compiled their maps (drawing)

Vladimir Atlasov 1696-1697 Undertook an expedition to Kamchatka, as a result of which it was annexed to Russia

Primary school teacher

GBOU secondary school No. 947

Nikolaeva Yulia Alekseevna

ABSTRACT

history lesson

held in 3rd grade

on the topic "Russian pioneers.

Geographic location of Asia.

Topic: Russian pioneers. Geographical position of Asia»

Tasks:

Educational: expand our understanding of the world around us; introduce the conqueror of Siberia - Yermak, the discoverer Nikitin.

Educational: cultivate love for the subject.

Developing: develop the ability to observe, draw conclusions.

Equipment:

Physical map of Russia

Presentation;

Cards;

Country name cards

Literature:

Lesson planning for the textbook N. Ya, Dmitrieva.

Board decoration

Physical

map

Russia

Stages

During the classes

Notes

I Organizational part

Hello guys! Have a seat.

II Statement of the problem

Today we will go on a very interesting journey with you and become real explorers. We will get acquainted with some Russian pioneers, as well as with the geographical position of Asia and the natural conditions on its territory. Guys, tell me, please, what is Asia? Well done. Indeed, Asia is one of the parts of the world on our planet. But before doing the research, let's formulate the questions we want to find answers to. Guys, what would you like to learn at the lesson today? (What was the name of the Russian pioneers? What territories did they discover? Where is Asia located? What does this part of the world look like on the map? What is the climate in Asia?...)

Well, we have formulated questions on the topic, and during the lesson we will try to answer all these questions.

Posting questions on the board

IV Discovery of new knowledge about Asia

Four centuries ago, to the east of the Ural Mountains, lands unknown to explorers lay. They said that behind the stone (as the Ural Mountains were called at that time) lies an immense land - go at least 2 years and you will not reach the end. In this region, there are untold riches: a lot of fur-bearing animals, fish, and in the icy Arctic Ocean - marine animals. Sable and arctic fox skins and walrus tusks were especially highly valued. And so, to the east, to the expanses of Siberia and the Far East, Russian people "capable of any work and military deed" went. These brave brave people who discovered new lands beyond the Ural Range were called pioneers. Even during the years of the Horde yoke, long-distance travels of Russian people did not stop. At that time, these lands were sparsely populated. And now, before you go on a journey with the pioneers, check how you know how to navigate.

Determine which side of the world is in relation to Moscow the White Sea, the Azov and Baltic Seas and the Pacific Ocean. Well done! What is hidden on the map behind the green, yellow and brown colors? (Plain, desert, mountains)

Novgorod played an important role in expanding the geographical knowledge of the Russian people (Slide 2). Over time, the path "from the Varangians to the Greeks" lost its meaning. Tell me, please, from which sea did this path go? (From Baltic to Black) Quite right! What was its purpose? (Trade route between Scandinavia, Northern Europe, Byzantium and Asia) Well done! As I said, this path has lost its meaning over time. Trade relations between Russia and Europe went through Novgorod and further along the Baltic Sea.

Novgorodians also paved the way to the North. First, they discovered the White Sea, on the islands of which the famous Solovetsky Monastery was founded. (Slide 3) It became the base for further travels. (Slide 4) Novgorodians on boats-ushkis went to the Barents Sea, and then along the coast, where on boats, where on dry land, they moved east (Slide 5) to the Kara Sea. Beyond the Urals, the Novgorodians found themselves in a part of the world that was unfamiliar to Russian people at that time - Asia. (Slide 6) In the north, travelers were met by harsh nature: a treeless swampy plain - tundra, a short summer with the sun not setting all day; (Slide 7) a long winter, when the polar night lasts for many months with fierce frosts and severe snowstorms. But the Novgorodians again and again sailed there in their small boats. They were attracted by the abundance of valuable fish, sea animals and fur-bearing animals. They also discovered many islands of the Arctic Ocean.

Listen to how the indigenous peoples - the Nenets - characterize their land: (Slide 8) “When visiting us, do not forget a fur hat, a warm coat and felt boots. We will ride reindeer and feed you deliciously cooked fish.”

(Slide 9) And to the south, to Palestine, where there are many shrines Orthodox Church, went Russian priests. It was also Asia - hot, dry, mountainous, alien to the Russian people, accustomed to the expanses of the plains.

(Slide 10) To the east, to Mongolia, during the time of the Horde yoke, Russian princes went to bow to the supreme Mongol khan. This is already the center of Asia, where steppes and deserts languish in summer from unbearable heat, and freeze in winter from unbearable cold.

Listen to how the indigenous peoples - the Mongols characterize their land: (Slide 11) “There is nothing better than our vast expanses. If you forgot your umbrella, do not be sad: rains in summer are rare here, but dry winds are a common thing.

And a completely different Asia was seen by the Tver merchant Afanasy Nikitin, who was the first of the Russian people, after a long journey along rivers, through seas, mountains and deserts, to reach India. (Slide 12) There he found himself among the luxurious tropical vegetation of the hot zone of the Earth. You will get to know this part of Asia a little later.

Listen to how the indigenous peoples - Indians characterize their land: (Slide 13) “Leave a heavy suitcase with clothes at home. It is hot over here! Still - it's not far from the equator! If you're lucky, a warm wind will blow from the sea and bring the long-awaited rain. And what amazing plants we have - (Slide 14) breadfruit, for example.

Now, guys, try to explain the reason for such different natural conditions in one part of the world - Asia? (Different natural areas)

Students on physical map Russia set flags on given objects

I use a presentation with a number of illustrations in the course of my story

VI Consolidation

Now, guys, we will check how well you have mastered the difference in natural conditions between different parts of the same continent - Asia. (Slide 15) Match the names of the parts of Asia and their characteristics using the arrows. You have 1 minute to complete the task. (Students complete the task) Well done guys! You did an excellent job. So we answered a few questions that we set ourselves at the beginning of the lesson: namely, the questions: Where is Asia? How does this part of the world look on the map? What is the climate in Asia?

Work on cards

VII Fizminutka

And now I'm going to ask you all to stand up. Listen to the words and repeat the movements after me.

Let's go on a hike.

How many discoveries are waiting for us!

We walk one after the other

Forest and green meadow.

(The teacher draws the attention of the children to beautiful butterflies flying across the clearing. The children run on their toes, waving their arms, imitating the flight of butterflies.)

We quickly went down to the river,

Bent over and washed.

One two three four,

That's how nicely refreshed.

(Hand movements are performed imitating swimming in different styles.)

VIII Introduction to new material

And we still have questions to which we have not yet found answers. Guys, what are these questions? Well done! And the first of them: what were the names of the Russian pioneers who participated in expanding knowledge about Asia and in its development. To find out who it is, solve very simple puzzles. Well done boys! You guessed it right - these discoverers are Afanasy Nikitin and Yermak Timofeevich. At that time, the land beyond the Urals was completely unknown. People had no idea what was there. Now this can be compared with our ideas about Mars. People had neither the appropriate equipment for studying, nor maps of Asia more or less corresponding to actual knowledge. However, people's interest led them to new discoveries. Since the 16th century, the annexation of Asian lands to Russia began. The first campaign was organized by a detachment of military Cossacks led by Ermak Timofeevich to the Urals. (Slide 16) The chronicle preserved the description of Yermak's appearance: medium height, broad-shouldered, flat-faced, black beard, thick, curly hair. And it was also reliably known that he was bold, decisive, smart and cunning. He gathered a detachment of the brave and established firm discipline among them. His squad invaded the territory of the Siberian Khanate and defeated the army of Khan Kuchum.

(Slide 18)Cossacks under the command of Yermak, went on a campaign for Stone Belt () from. The initiative of this campaign belonged to Yermak himself.

It is important to note that at the disposal of the future enemy of the Cossacks, Khan Kuchum, there were forces that were several times superior to Yermak's squad, but armed much worse.

The Cossacks climbedup the Chusovaya and along its tributary, the river, to the Siberian portage separating the basins of the Kama and, and dragged the boats along the portage into the Zheravlya River (). Here the Cossacks were supposed to spend the winter. During the winter, Yermak sent a detachment of associates to explore a more southerly route along the Neiva River. But the Tatar Murza defeated Yermak's reconnaissance detachment.

Only in the spring, along the rivers Zheravl, and, sailed into. They broke twice, on the Tour and at the mouth. sent against the Cossacks, with a large army, but this army was also defeated by Yermak on the shore. Finally, on, near Chuvashev, the Cossacks inflicted a final defeat on the Tatars in. Kuchum left the notch that protected the main city of his khanate, Siberia, and fled south to the Ishim steppes.

Yermak entered Siberia, abandoned by the Tatars.

Yermak used summer to conquer the Tatar towns and along the Irtysh and Ob rivers, meeting stubborn resistance everywhere.Yermak sent a messenger to Tsar Ivan the Terrible with the news of the conquest of new lands. This was also Asia. But again another Asia, where the taiga reigns. This part of Asia is called Siberia. You will get to know her a little later.

He received him very affectionately, gave rich gifts to the Cossacks and sent them reinforcements. The royals arrived at Yermak in the autumn of 1583, but their detachment could not deliver significant assistance to the Cossack squad, which had greatly diminished in battles. Atamans perished one by one.

Ermak Timofeevich himself also died.On that day, with only 50 Cossacks, he went to look for a caravan with food and provisions. Khan Kuchum managed to establish continuous observation of Yermak's detachment. At night, when the Cossacks fell asleep on the banks of the Irtysh, the Cossacks attacked them. Yermak fought to the last opportunity, then, under the pressure of dozens of enemies, he rushed into the water, trying to swim across the river. But the wound he received and heavy weapons pulled him to the bottom. Yermak is still one of the most revered heroes in the history of the Don Cossacks. They call him the conqueror of Siberia. There is no exact data on his origin, but all chronicles call him a Don Cossack.

And now, based on the map, answer me a few questions. From which city did Yermak's squad start the campaign to the Urals? Whose initiative was this performance? What river did they go up? Which tributary of the Chusovaya River did they move on? How did they get into the Zharovlya River? On what river did Yermak send his followers to explore the southern route? What happened to the squad? How many times did Yermak's squad defeat the detachments of the Siberian Tatars? Whose army defeated Yermak on the banks of the Tobol River? In what battle did Yermak's squad inflict a final defeat on the Tatars? Well done boys. I see that you have been listening to me carefully. And now we can move on to another pioneer.

As I said, a completely different Asia was seen by the Tver merchant Afanasy Nikitin, (Slide 19) who, after a long journey along rivers, through seas, mountains and deserts, reached the shores of India. Show me on a map, please. Well done! In his notebook, Nikitin wrote down everything that surprised him in foreign countries. He wrote about overseas birds, about palaces and temples.

“There are seven gates in the Sultan's palace. And a hundred watchmen are sitting at the gates ... And the palace is wonderful grand, all with carvings and gold. Each stone is carved and painted with gold ...

The Sultan leaves for fun with his mother and his wife. And with him ten thousand people on horseback, and fifty thousand on foot, and two hundred elephants dressed in gilded armor. And in front of him are a hundred trumpeters, and a hundred dancers, and three hundred horses in a golden harness, and a hundred monkeys behind him ... ”Nikitin marveled at everything - and dancers, and monkeys and elephants. “And to the elephants they bind to the snout and to the teeth great swords, two pounds forged, and dress them in damask armor, but all with cannons and arrows ...”

“But the monkeys live in the forest, yes they have a prince of monkeys, yes they walk with their army, but whoever touches them complains to their prince, and he sends his army to him. And they, having come to the city, will destroy the yards and beat people. And their rati, they say, are very many, and they have their own language.

(Slide 20) Nikitin was not destined to return home. He died not far from Smolensk. His diaries were delivered to the Grand Duke of Moscow, Ivan III.

At the presentation, a portrait of Afanasy Nikitin

IX Anchoring

And now, in order to analyze whether you have learned everything in the lesson, I suggest that you fill out a table. Pay attention to the board. Look at the table. Think about how you would fill it out. You can also use the reference words below the table. Let's start with Ermak ...

X Debriefing

So guys, what did we study today? What have you learned about Asia? What were the names of the pioneers that were discussed in today's lesson? What do you remember from their biography?

XI Reflection

Well done boys! Now look at your desks. Those who have 5 or more stars worked perfectly today. Those who have 3-4 stars worked well. And those who have 2 or less, I hope that next time you will be more active in the lesson.

XII Homework

Your homework will be to complete these tables now on your own. And our journey has come to an end. Thank you for your work. Goodbye!

Restore Compliance

North Asia

middle Asia

South Asia

“There is nothing better than our endless expanses. If you forgot your umbrella, don’t be sad: rains in summer are rare here, but dry winds are a common thing.”

“Leave a heavy suitcase full of clothes at home. It is hot over here! Still - it's not far from the equator! If you're lucky, a warm wind will blow from the sea and bring the long-awaited rain. And what amazing plants we have - breadfruit, for example.

“Going to visit us, do not forget a fur hat, a warm coat and felt boots. We will ride reindeer and feed you deliciously cooked fish.”

Fill the table.

Traveler's last name

Purpose of Travel

Traveler personality

Time travel

People's ideas about the space beyond the Urals in a given period of time

Travel results

Ermak

Nikitin

Russian pioneers

The Russian Tsar Peter I has long been tormented by the question of whether the Asian continent is connected to America. And one day he ordered to equip an expedition, headed by a foreign navigator Vitus Bering. Lieutenant Alexei Ilyich Chirikov became the assistant to the leader of the sea voyage.

Ships "St. Peter" and "St. Paul" on the high seas

On the appointed day, the travelers set off on a difficult journey. The road on sledges, carts and boats passed through the East European and Siberian plains. Exactly two years it took the pioneers to cross this space. At the last stage of the journey, the travelers seemed to be waiting for a new blow of fate. V harsh conditions In the Siberian winter, they had to travel great distances, often harnessing themselves instead of horses and dogs to sledges loaded with the necessary equipment and provisions. Be that as it may, the members of the Russian expedition reached the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk. Having crossed to the opposite shore of the sea, the travelers built a ship that helped them reach the mouth of the Kamchatka River. Then they sent the ship to the northeast and went to the Gulf of Anadyr. Beyond the Gulf of Anadyr, travelers discovered another bay, which was called the Gulf of the Cross. And they called the nearby bay the Bay of Providence. Then the boat of the Russian discoverers entered the strait, at the entrance to which there was an island, called by travelers the island of St. Lawrence.

Traveler Vitus Bering

Bering then gave the order to send the ship north. Soon the shores of Asia disappeared over the horizon. For two days, Vitus Bering led an expedition to the north. However, on the way they did not meet a single islet or archipelago. Then Alexei Ilyich Chirikov suggested that the captain change the ship's course and send it to the west. But Bering refused to comply with the request of the lieutenant and ordered the helmsman to turn the ship to the south. Everyone understood that the leader of the expedition had decided to return to the capital. On the way home, the travelers managed to make another discovery - they discovered an island, which they called the island of St. Diomede. A year later, Vitus Bering again led the expedition sent by the Russian Tsar in search of the shores of America. However, his second trip did not give positive results. Somewhat later, the navigator Ivan Fedorov and the surveyor Mikhail Gvozdev took up the study of the strait, named after Bering. In addition, they were able to approach the American coast and even map the waters between Alaska and Chukotka.

Geyser in Kamchatka

Meanwhile, Vitus Bering equipped a new expedition to the shores of America. On a difficult journey, he was again accompanied by Alexei Ilyich Chirikov. In addition, scientists-geographers, sent on a trip by the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, also took part in the expedition. Then a group of researchers was named the Academic Detachment of the Great Northern Expedition.

The new expedition consisted of two ships. The first, which was called "St. Peter", was commanded by Bering, and the second, called "St. Paul", Chirikov. On board each of the ships were 75 crew members. First of all, it was decided to take a course to the southeast. However, no land was found. After that, the ships took different courses.

In the middle of summer, Bering's ship reached the shores of America. Numerous mountains were visible to the sailors from the ship. The highest of them was called Mount St. Elijah. The expedition then set off on its return journey. On the way home, travelers met a chain of small islands. The largest island was named Tumanny (later renamed Chirikov Island).

Further, the ship "Saint Peter" went along the coast of the Aleutian Islands, which the travelers considered the American shores. However, the researchers did not land on the shore and continued swimming. Soon they met an unknown land on their way, which Bering mistook for Kamchatka. Then the leader of the expedition decided to stay there for the winter.

The sailors got off the ship and set up camp. By that time, many members of the expedition, being seriously ill, had died. On December 8, 1741, the organizer and leader of the campaign, Vitus Bering, also died.

The scientist L. S. Berg at one time put forward his own assumption regarding the opening of the strait, named after Bering. He wrote: “The first ... was not Dezhnev and not Bering, but Fedorov, who not only saw the earth, but was the first to put it on the map ...”

Those who were able to resist the hardships of travel remained to live on the island. Their main occupation on uncharted land was hunting for marine animals. Naturalist Georg Steller discovered a hitherto unknown animal off the coast of the island, which was called a sea cow. It should be noted that at present the sea cow is considered an extinct species. Last time she was seen in late XIX century.

With the advent of spring, the surviving Russian sailors began to gather on their way back. Their ship had almost completely rotted by that time. Cossack Savva Starodubtsev came to the rescue of the team. With the help of his comrades, he built a light boat, which, after almost three weeks, delivered travelers to the shores of Kamchatka.

Kamchatka

The campaign of "St. Paul", commanded by Alexei Ilyich Chirikov, also turned out to be tragic. One day the expedition landed on the island. The captain sent several people into the interior of the island. After they did not return to the ship, he sent four more to reconnoiter. However, they were lost in the depths of an unknown land. After that, Chirikov gave the command to send the ship home. Judging by the remaining documents, Chirikov's ship reached the coast of America much earlier than Bering's ship. However, for a long time these papers were considered strictly secret. Therefore, it is generally accepted in science that Vitus Bering was the first to reach the shores of America from Asia.

From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (RU) of the author TSB From the book Great Soviet Encyclopedia (YAK) of the author TSB From the book Siberia. Guide author Yudin Alexander Vasilievich From the book 100 great theaters of the world author Smolina Kapitolina Antonovna From the book Winged words author Maksimov Sergey Vasilievich From the book 100 great aviation and astronautical records author Zigunenko Stanislav NikolaevichThe Russians are Coming The further history of the settlement and development of Siberia by the Russians is connected with the legendary Yermak. In a letter of 1582, Ivan the Terrible stated that Yermak and his retinue “quarreled with the Nogai Horde, beat the Nogai ambassadors on the Volga while transporting<…>and our people

From the book I know the world. Great Journeys author Markin Vyacheslav AlekseevichRussian Seasons "Russian Seasons" - annual theatrical performances of Russian opera and ballet at the beginning of the 20th century in Paris (since 1906), London (since 1912) and other cities of Europe and the USA. The Seasons were organized by Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev (1872-1929).S. P. Diaghilev - Russian

From the book Germany and the Germans. What guidebooks are silent about author Tomchin Alexander From the book Geographical discoveries author Khvorostukhina Svetlana AlexandrovnaRussian ideas Thus, in practice, the validity of the calculations of the outstanding Russian scientist K. E. Tsiolkovsky was proved. Back in the 80s of the 19th century, when small controlled balloons had just begun to be built all over the world, he scientifically proved the possibility and expediency of

From the book Encyclopedia of America's Largest Cities author Korobach Larisa RostislavovnaPioneers of the Northwest In 1496, the Spanish ambassador in London reported to the King and Queen of Spain that a captain had proposed the English king project of sailing to India, just as Columbus did. Spanish monarchs protest against 'violation of rights'

From the book 8000 fishing tips from a connoisseur author Goryainov Alexey Georgievich10.2. Russian Germans or German Russians? Russian Germans, that is, our compatriots with German roots, have the right to come to Germany for permanent residence. These are the descendants of those Germans who, at the invitation of Catherine II, settled in Russia and were famous with us for their

From the book South Africa. Demo version for tourists from Russia the author Zgersky IvanRussians in Antarctica The first Russian scientific expedition to Antarctica was organized in 1956. Back in the early 30s of the 20th century, an expedition to a distant mainland was planned in the USSR. Then the geographers Rudolf Samoylovich were to become its leaders, in 1928

From the author's bookRussian Bostonians There are a lot of Russian-speaking people in Boston and it can be called a Russian city. When you walk around Boston, it seems that every second inhabitant speaks Russian and the facial expression is purely Russian. Historically, Boston

From the author's bookRussians in Los Angeles Los Angeles is one of the largest centers of Russian-speaking immigrants in America. Immigrants from the former USSR live in almost all areas and suburbs of Los Angeles. The largest number of "Russian-speaking" residents in the

From the author's book From the author's bookRussians in South Africa How many are there? Nobody knows. According to the Russian Consulate in Cape Town, about 300 Russian citizens are registered. Much more in Johannesburg. Of course, not everyone registers. Democracy has been untied, and it is unrealistic to count the people. Around

(c. 1605, Veliky Ustyug - early 1673, Moscow) - an outstanding Russian navigator, explorer, traveler, explorer of Northern and Eastern Siberia, Cossack ataman, and also a fur trader, the first of the famous European navigators, in 1648, for 80 years earlier than Vitus Bering, he passed the Bering Strait, which separates Alaska from Chukotka.

It is noteworthy that Bering did not manage to pass the entire strait, but had to limit himself to swimming only in its southern part, while Dezhnev passed through the strait from north to south, along its entire length.

Biography

Information about Dezhnev has reached our time only for the period from 1638 to 1671. Born in Veliky Ustyug (according to other sources - in one of the Pinega villages). When Dezhnev left from there to “seek happiness” in Siberia is unknown.

In Siberia, he first served in Tobolsk, and then in Yeniseisk. Among the great dangers of 1636-1646, he "humbled" the Yakuts. From Yeniseisk, in 1638, he moved to the Yakut prison, which had just been founded in the neighborhood of the still unconquered tribes of foreigners. Dezhnev's entire service in Yakutsk represents a series of tireless labors, often associated with danger to life: in 20 years of service here, he was wounded 9 times. Already in 1639-40. Dezhnev subjugates the native prince Sahey.

In the summer of 1641 he was assigned to the detachment of M. Stadukhin, got with him to the prison on the Oymyakon (the left tributary of the Indigirka).

In the spring of 1642, up to 500 Evens attacked Ostrozhek, Cossacks, Yasak Tunguses and Yakuts came to the rescue. The enemy retreated with losses. At the beginning of the summer of 1643, the detachment of Stadukhin, including Dezhnev, on the built koch went down the Indigirka to the mouth, crossed the sea to the Alazeya River and met the koch Erila in its lower reaches. Dezhnev managed to persuade him to take joint action, and the united detachment, led by Stadukhin, moved east on two ships.

In mid-July, the Cossacks reached the Kolyma delta, were attacked by the Yukagirs, but broke through up the river and in early August they set up an ostrog (now Srednekolymsk) on its middle course. Dezhnev served in Kolyma until the summer of 1647. In the spring, with three companions, he delivered a load of furs to Yakutsk, repelling an Even attack along the way. Then, at his request, he was included in the fishing expedition of Fedot Popov as a collector of yasak. However, the heavy ice situation in 1647 forced the sailors to return. It was not until the following summer that Popov and Dezhnev moved east with 90 people on seven koches.

According to the generally accepted version, only three ships reached the Bering Strait - two were lost in a storm, two were missing; another shipwrecked in the strait. Already in the Bering Sea in early October, another storm separated the two remaining koches. Dezhnev with 25 satellites was thrown back to the Olyutorsky Peninsula, and only ten weeks later they were able to reach the lower reaches of the Anadyr. This version contradicts the testimony of Dezhnev himself, recorded in 1662: six ships out of seven passed the Bering Strait, and five ships, including Popov's ship, died in the Bering Sea or in the Gulf of Anadyr in "bad weather".

One way or another, after crossing the Koryak Highlands, Dezhnev and his comrades reached Anadyr "cold and hungry, naked and barefoot." Of the 12 people who went in search of camps, only three returned; somehow 17 Cossacks survived the winter of 1648/49 on Anadyr and were even able to build river boats before the ice drifted. In the summer, having climbed 600 kilometers against the current, Dezhnev founded a yasak winter hut on the Upper Anadyr, where he met the new year, 1650. In early April, detachments of Semyon Motora and Stadukhin arrived there. Dezhnev agreed with Motoroy to unite and in the fall made an unsuccessful attempt to reach the Penzhina River, but, having no guide, wandered in the mountains for three weeks.

In late autumn, Dezhnev sent some people to the lower reaches of the Anadyr to purchase food from local residents. In January 1651, Stadukhin robbed this food detachment and beat the purveyors, while in mid-February he himself went south - to Penzhina. The Dezhnevites lasted until spring, and in the summer and autumn they were engaged in the food problem and reconnaissance (unsuccessfully) of "sable places". As a result, they got acquainted with the Anadyr and most of its tributaries; Dezhnev drew up a drawing of the pool (not yet found). In the summer of 1652, in the south of the Anadyr estuary, he discovered the richest walrus rookery with a huge amount of "dead tooth" - fangs of dead animals on the shallows.

Navigation map

and the campaign of S. Dezhnev in 1648–1649.

In 1660, at his request, Dezhnev was replaced, and with a load of "bone treasury" he crossed overland to Kolyma, and from there by sea to the Lower Lena. After wintering in Zhigansk, through Yakutsk, he reached Moscow in September 1664. For the service and fishing of 289 pounds (slightly more than 4.6 tons) of walrus tusks in the amount of 17,340 rubles, a full payment was made to Dezhnev. In January 1650, he received 126 rubles and the rank of Cossack ataman.

Upon his return to Siberia, he collected yasak on the Olenyok, Yana and Vilyui rivers, at the end of 1671 he delivered a sable treasury to Moscow and fell ill. He died early in 1673.

During the 40 years of his stay in Siberia, Dezhnev participated in numerous battles and skirmishes, had at least 13 wounds, including three severe ones. Judging by the written testimonies, he was distinguished by reliability, honesty and peacefulness, the desire to do the job without bloodshed.

A cape, an island, a bay, a peninsula and a village are named after Dezhnev. In the center of Veliky Ustyug in 1972 a monument was erected to him.

Since we are talking about Dezhnev, it is necessary to mention Fedot Popov- the organizer of this expedition.

Fedot Popov, a native of Pomor peasants. For some time he lived in the lower reaches of the Northern Dvina, where he acquired the skills of a sailor and mastered the letter. A few years before 1638, he appeared in Veliky Ustyug, where he was hired by the wealthy Moscow merchant Usov and established himself as an energetic, intelligent and honest worker.

In 1638, already in the position of clerk and confidant trading company Usova was sent with a partner to Siberia with a large consignment of "any goods" and 3.5 thousand rubles (a significant amount at that time). In 1642, both reached Yakutsk, where they parted ways. With a trading expedition, Popov moved on to the Olenyok River, but he failed to bargain there. After returning to Yakutsk, he visited Yana, Indigirka and Alazeya, but all was unsuccessful - other merchants were ahead of him. By 1647, Popov arrived in Kolyma and, having learned about the distant river Pogycha (Anadyr), where no one had yet penetrated, he planned to get to it by sea in order to compensate for the losses he had suffered during several years of vain wanderings.

In Srednekolymsky Ostrozhka, Popov gathered local industrialists and built and equipped 4 kochas with the money of the merchant Usov, as well as with the money of his companions. The Kolyma clerk, realizing the importance of the undertaking, gave Popov an official status, appointing him a kisser (a customs official whose duties also included collecting duties on fur transactions). At the request of Popov, 18 Cossacks were assigned to the fishing expedition under the command of Semyon Dezhnev, who wished to participate in the enterprise for the discovery of "new lands" as a yasak collector. But the head of the voyage was Popov, the initiator and organizer of the whole thing. Shortly after going to sea in the summer of 1647, due to the difficult ice conditions, the Kochi returned back to Kolyma. Popov immediately began preparing for a new campaign. Thanks to the newly invested funds, he equipped 6 koches (and Dezhnev hunted in the upper Kolyma in the winter of 1647-1648). In the summer of 1648, Popov and Dezhnev (again as collectors) went down the river to the sea. Here they were joined by the seventh coch Gerasim Ankudinov, who unsuccessfully applied for the place of Dezhnev. The expedition, consisting of 95 people, for the first time passed through the Chukchi Sea at least 1000 km of the northeastern coast of Asia and in August reached the Bering Strait, where Ankudinov's koch was wrecked. Fortunately for the people, he moved to Koch Popov, and the rest were accommodated on 5 other ships. On August 20, sailors landed somewhere between Capes Dezhnev and Chukotsky to repair ships, collect "vykidnik" (fin) and replenish fresh water. The Russians saw islands in the strait, but it was impossible to determine which ones. In a fierce skirmish with the Chukchi or the Eskimos, Popov was wounded. In early October, in the Bering Sea or in the Gulf of Anadyr, a strong storm scattered the flotilla. Dezhnev found out the further fate of Popov five years later: in 1654, on the shores of the Gulf of Anadyr, in a skirmish with the Koryaks, he managed to recapture a Yakut woman, Popov's wife, whom he took with him on a campaign. This first Russian Arctic navigator named Kivil informed Dezhnev that Popov's koch had been washed ashore, most of the sailors were killed by the Koryaks, and only a handful of Russians fled in boats, and Popov and Ankudinov died of scurvy.

Popov's name is undeservedly forgotten. He rightfully shares the glory of opening a passage from the Arctic to the Pacific Ocean with Dezhnev.

(1765, Totma, Vologda province - 1823, Totma, Vologda province) - explorer of Alaska and California, creator of Fort Ross in America. Totem tradesman. In 1787 he reached Irkutsk, on May 20, 1790 he signed a contract with the Kargopol merchant A. A. Baranov, who lived in Irkutsk, on a sea voyage to the American shores in the company of Golikov and Shelikhov.

The well-known explorer of the North American continent and the founder of the famous Fort Ross, Ivan Kuskov, even in his youth, enthusiastically listened to the stories and memories of travelers who came to their land from distant uncharted places, and even then he became seriously interested in navigation and the development of new lands.

As a result, already at the age of 22, Ivan Kuskov went to Siberia, where he signed an escort contract to the American shores. Great importance Ivan Kuskov had an extensive organizational activity on the island of Kodiak for the development and settlement of new lands, the construction of settlements and fortifications. For some time Ivan Kuskov acted as chief manager. Later, he commanded the Konstantinovsky redoubt under construction on the island of Nuchev in the Chugatsky Bay, went out to explore the island of Sitkha on the brig "Ekaterina" at the head of a flotilla of 470 canoes. Under the command of Ivan Kuskov, a large party of Russians and Aleuts fished on the west coast of the American mainland and was forced to fight with local Indians to assert their positions. The result of the confrontation was the construction of a new fortification on the island and the construction of a settlement called Novo-Arkhangelsk. It was he who in the future was destined to acquire the status of the capital of Russian America.

The merits of Ivan Kuskov were noted by the ruling circles, he became the owner of the medal "For Diligence", cast in gold and the title of "Advisor of Commerce".

Having led the sea voyage campaign to develop the lands of California, which was then under the rule of Spain, Ivan Kuskov opened a new page in his life and work. On the ship "Kodiak" he visited the island of Trinidad in Bodega Bay, and on the way back he went to Douglas Island. Moreover, everywhere the pioneers buried boards with the coat of arms of their country in the ground, which meant the annexation of territories to Russia. In March 1812, on the Pacific coast, north of San Francisco Bay, Ivan Kuskov laid the first major fortress in Spanish California - "Fort Slavensk" or otherwise "Fort Ross". The creation of a fortress and an agricultural settlement in favorable climatic conditions helped to provide northern Russian settlements in America with food. The areas of fishing for sea animals expanded, a shipyard was built, a forge, a locksmith, a carpentry and a fuller's workshop were opened. For nine years, Ivan Kuskov was the head of the fortress and the village of Ross. Ivan Kuskov died in October 1823 and was buried in the fence of the Spaso-Sumorin Monastery, but the grave of the famous researcher has not survived to this day.

Ivan Lyakhov- Yakut merchant-industrialist who discovered Fr. Boiler house of the Novosibirsk Islands. From the middle of the XVIII century. hunted Mammoth bone on the mainland, in the tundra, between the mouths of the Anabar and Khatanga rivers. In April 1770, in search of a mammoth bone, he crossed the ice from Svyatoy Nos through the Dmitry Laptev Strait to about. Near or Eteriken (now - Bolshoi Lyakhovsky), and from its northwestern tip - on about. Small Lyakhovsky. After returning to Yakutsk, he received from the government a monopoly right to trade on the islands he visited, which, by decree of Catherine II, were renamed Lyakhovsky. In the summer of 1773, with a group of industrialists, he went by boat to the Lyakhovsky Islands, which turned out to be a real "cemetery of mammoths". North of about. Maly Lyakhovsky saw the "Third" large island and crossed to it; for the winter in 1773/74 he returned to about. Near. One of the industrialists left a copper boiler on the "Third" island, which is why the newly discovered island began to be called Kotelny (the largest of the Novosibirsk Islands). I. Lyakhov died in the last quarter of the 18th century. After his death, the monopoly right to trade on the islands passed to the merchants Syrovatsky, who sent Ya. Sannikov there for new discoveries.

Yakov Sannikov(1780, Ust-Yansk - not earlier than 1812) Russian industrialist (XVIII-XIX centuries), explorer of the Novosibirsk Islands (1800-1811). He discovered the islands of Stolbovoy (1800) and Faddeevsky (1805). He expressed an opinion about the existence to the north of the Novosibirsk Islands of a vast land, the so-called. Sannikov Lands.

In 1808 Minister of Foreign Affairs and Commerce N.P. Rumyantsev organized an expedition to explore the recently discovered New Siberian Islands - the "Great Land". M.M. was appointed head of the expedition. Gedenstrom. Arriving in Yakutsk, Gedenstrom established that "it was discovered by the tradesmen Portnyagin and Sannikov, who live in the Ust-Yansk village." February 4, 1809 Gedenstrom arrived in Ust-Yansk, where he met with local industrialists, among whom was Yakov Sannikov. Sannikov served as a foreman (foreman of an artel) with the Syrovatsky merchants. He was an amazingly brave and inquisitive person, whose whole life was spent wandering through the vast expanses of the Siberian North. In 1800 Sannikov crossed from the mainland to Stolbovoy Island, and five years later he was the first to set foot on an unknown land, which later received the name of Faddeevsky Island, after the industrialist who built a winter hut on it. Then Sannikov participated in the trip of the industrialist Syrovatsky, during which the so-called Great Land was discovered, called New Siberia by Matvey Gedenstrom.

The meeting with Sannikov, one of the discoverers of the New Siberian Islands, was a great success for Matvey Matveyevich. In the face of Sannikov, he found a reliable assistant and decided to expand the area of work of his expedition. Sannikov, following Gedenstrom's instructions, crossed the strait between the Kotelny and Faddeevsky islands in several places and determined that its width ranged from 7 to 30 versts.

“On all these lands,” Pestel wrote to Rumyantsev, “there is no standing forest; polar bears, gray and white wolves are found among animals; there are a great many deer and arctic foxes, also brown and white mice; from birds in winter there are only white partridges, in summer ", according to the description of the tradesman Sannikov, geese molt there a lot, also ducks, tupans, waders and other small birds are enough. This land, which Gedenstrom traveled around, he called New Siberia, and the shore where the cross was placed, Nikolaevsky. "

Gedenstrom decided to send a group of industrialists to New Siberia under the command of Yakov Sannikov.

Sannikov discovered a river that flowed northeast from the Wooden Mountains. He said that members of his artel walked along its shore "60 miles deep and saw water disputed from the sea." In Sannikov's testimony, Gedenstrom saw evidence that New Siberia in this place was probably not very wide. It soon became clear that New Siberia was not a mainland, but not a very large island.

March 2, 1810 the expedition, led by Gedenstrom, left the Posadnoe winter hut and headed north. Among the participants of the expedition was Yakov Sannikov. The ice in the sea turned out to be very shaken up. Instead of six days, the journey to New Siberia took about two weeks. The travelers crossed on sleds to the mouth of the Indigirka, and from there to the eastern coast of New Siberia. Another 120 miles to the island, the travelers noticed the Wooden Mountains on the southern coast of this island. Having rested, we continued the inventory of New Siberia, which we started last year. Sannikov crossed New Siberia from south to north. Coming to its northern shore, he saw blue far to the northeast. It was not the blue of the sky; During his many years of travel Sannikov saw her more than once. It was this blue that Stolbovoy Island seemed to him ten years ago, and then Faddeevsky Island. It seemed to Yakov that it was worth driving 10-20 versts, either mountains or the shores of an unknown land would emerge from the blue. Alas, Sannikov could not go: he was with one team of dogs.

Gedenstrom, after meeting with Sannikov, went on several sleds with the best dogs to the mysterious blue. Sannikov believed that this was land. Gedenshtrom later wrote: "The imaginary land turned into a ridge of the highest ice masses of 15 or more sazhens in height, spaced from one another at 2 and 3 versts. In the distance, as usual, they seemed to us a solid coast" ...

In the autumn of 1810 on Kotelny, on the northwestern coast of the island, in those places where not a single industrialist reached, Sannikov found a grave. Next to it was a narrow high sled. Her device said that "people dragged her with straps." A small wooden cross was placed on the grave. On one side of it, an illegible ordinary church inscription was carved. Near the cross were spears and two iron arrows. Not far from the grave, Sannikov discovered a quadrangular winter hut. The nature of the building indicated that it had been cut down by Russian people. Having carefully examined the winter hut, the industrialist found several things made, probably, with an ax from a deer antler.

In the "Note on the things found by the tradesman Sannikov on Kotelny Island" in question and about something else, perhaps the most interesting fact: being on Kotelny Island, Sannikov saw "high stone mountains" in the north-west, about 70 versts away. On the basis of this story by Sannikov, Gedenstrom marked in the upper right corner of his final map the coast of an unknown land, on which he wrote: "The land seen by Sannikov." Mountains are drawn on its coast. Gedenstrom believed that the shore seen by Sannikov connected with America. It was the second Sannikov Land - a land that did not really exist.

In 1811 Sannikov, together with his son Andrei, worked on Faddeevsky Island. He explored the northwestern and northern coasts: bays, capes, bays. He advanced on sleds pulled by dogs, spent the night in a tent, ate venison, crackers and stale bread. The nearest dwelling was 700 miles away. Sannikov was finishing his survey of Faddeevsky Island when he suddenly saw the contours of an unknown land in the north. Without losing a moment, he rushed forward. Finally, from the top of a high hummock, he saw a dark stripe. It widened, and soon he distinctly distinguished a wide wormwood stretching along the entire horizon, and behind it - an unknown land with high mountains. Gedenshtrom wrote that Sannikov traveled "no more than 25 versts, when he was held back by a polynya that stretched in all directions. The earth was clearly visible, and he believes that it was then 20 versts away from him." According to Gedenstrom, Sannikov's report about the "open sea" testified that the Arctic Ocean, which lies behind the New Siberian Islands, does not freeze and is convenient for navigation "and that the coast of America really lies in the Arctic Sea and ends with Kotelny Island."

Sannikov's expedition completely explored the shores of Kotelny Island. In its hinterland, travelers found "in great abundance" the heads and bones of bulls, horses, buffaloes and sheep. This means that in ancient times the New Siberian Islands had a milder climate. Sannikov discovered "many signs" of the dwellings of the Yukaghirs, who, according to legend, retired to the islands from a smallpox epidemic 150 years ago. At the mouth of the Tsareva River, he found the dilapidated bottom of the ship, made of pine and cedar wood. Its seams were caulked with tar bast. On the west coast, travelers encountered whale bones. This, as Gedenstrom wrote, proved that "from Kotelny Island to the north, the vast Arctic Ocean stretches unhindered, not covered with ice, like the Arctic Sea under the mother land of Siberia, where whales or their bones have never been seen." All these finds are described in the "Journal of personal explanations of the tradesman Sannikov, non-commissioned officer Reshetnikov and notes kept by them during the survey and flying on Kotelny Island ..." Sannikov did not see the stone mountains of the land either in spring or in summer. She seemed to have vanished into the ocean.

January 15, 1812 Yakov Sannikov and non-commissioned officer Reshetnikov arrived in Irkutsk. This ended the first search for the Northern Continent undertaken by Russia at the beginning of the 19th century. The earth has taken on its true form. Four of them were discovered by Yakov Sannikov: these are the islands of Stolbovoy, Faddeevsky, New Siberia and Bunge Land. But, by the will of fate, his name gained great fame thanks to the lands that he saw from afar in the Arctic Ocean. Receiving nothing for his labors, except for the right to collect mammoth bones, Sannikov explored all the major New Siberian Islands on dogs. Two of the three lands seen by Sannikov in various places in the Arctic Ocean appeared on the map. One, in the form of a part of a huge land with mountainous shores, was plotted to the north-west of Kotelny Island; the other was shown in the form of mountainous islands stretching from the meridian of the eastern coast of Fadeyevsky Island to the meridian of Cape Vysokoe in New Siberia, and named after him. As for the land to the northeast of New Siberia, a sign was placed at the place of its alleged location, which denotes an approximate value. Subsequently, the islands of Zhokhov and Vilkitsky were discovered here.

Thus, Yakov Sannikov saw unknown lands in three different places in the Arctic Ocean, which then occupied the minds of geographers all over the world for decades. Everyone knew that Yakov Sannikov had made major geographical discoveries even earlier, which made his messages more convincing. He himself was convinced of their existence. As it appears from the letter of I.B. Pestelya N.P. Rumyantsev, the traveler intended to "continue the discovery of new islands, and above all the land that he saw north of the Kotelny and Faddeyevsky Islands," and asked to give each of these islands to him for two or three years.

Pestel found Sannikov's proposal "very beneficial for the government." Rumyantsev adhered to the same point of view, at whose direction a report was prepared on the approval of this request. There is no record in the archives whether Sannikov's proposal was accepted.

"Sannikov Land" was searched in vain for more than a hundred years, while Soviet sailors and pilots in 1937-1938. did not prove definitively that such a land does not exist. Probably, Sannikov saw the "ice island".

Russian and Soviet explorers of Africa.

Among the explorers of Africa, a prominent place is occupied by the expeditions of our domestic travelers. In the studies of Northeast and Central Africa, he contributed huge contribution mining engineer Egor Petrovich Kovalevsky. In 1848, he explored the Nubian desert, the Blue Nile basin, mapped the vast territory of Eastern Sudan and made the first suggestion about the location of the sources of the Nile. Kovalevsky paid much attention to the study of the peoples of this part of Africa and their way of life. He was indignant at the "theory" of the racial inferiority of the African population.

Travels Vasily Vasilyevich Junker in 1875-1886 enriched geographical science with accurate knowledge of the eastern region of Equatorial Africa. Juncker conducted research in the area of the upper Nile: he made the first map of the area.

The traveler visited the rivers Bahr el-Ghazal and Uela, explored the complex and intricate system of rivers of its vast basin and clearly defined the previously disputed line of the Nile-Congo watershed for 1200 km. Juncker made a number of large-scale maps of this territory and paid much attention to descriptions of flora and fauna, as well as the way of life of the local population.

A number of years (1881-1893) spent in North and Northeast Africa Alexander Vasilievich Eliseev, who described in detail the nature and population of Tunisia, the lower reaches of the Nile and the coast of the Red Sea. In 1896-1898. traveled in the Abyssinian Highlands and in the Blue Nile basin Alexander Ksaverevich Bulatovich, Petr Viktorovich Shchusyev, Leonid Konstantinovich Artamonov.

In Soviet times, an interesting and important trip to Africa was made by the famous scientist - botanical geographer Academician Nikolay Ivanovich Vavilov. In 1926, he arrived from Marseilles in Algeria, got acquainted with the nature of the large Biskra oasis in the Sahara, the mountainous region of Kabylia and other regions of Algeria, traveled through Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Somalia, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Vavilov was interested in the ancient centers of cultivated plants. He conducted especially large studies in Ethiopia, having traveled more than 2 thousand km through it. More than 6,000 samples of cultivated plants were collected here, including 250 varieties of wheat alone, and interesting materials were obtained on many wild plants.

In 1968-1970. in Central Africa, in the Great Lakes region, geomorphological, geological-tectonic, geophysical studies were carried out by an expedition led by a corresponding member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Professor Vladimir Vladimirovich Belousov, which specified data on the tectonic structure along the line of the great African fault. This expedition visited some places for the first time after D. Livingston and V. V. Juncker.

Abyssinian expeditions of Nikolai Gumilyov.

First expedition to Abyssinia.

Although Africa has attracted Gumilyov, the decision to go there came suddenly and on September 25 he went to Odessa, from there to Djibouti, then to Abyssinia. The details of this journey are unknown. It is only known that he visited Addis Ababa for a formal reception at the Negus. The friendly relations of mutual sympathy that arose between the young Gumilyov and the wise experience of Menelik II can be considered proven. In the article “Did Menelik Die?” the poet described the troubles that took place at the throne, as he reveals his personal attitude to what is happening.

Second expedition to Abyssinia.

The second expedition took place in 1913. It was better organized and coordinated with the Academy of Sciences. At first, Gumilyov wanted to cross the Danakil desert, study the little-known tribes and try to civilize them, but the Academy rejected this route as expensive, and the poet was forced to propose a new route:

I had to go to the port of Djiboutti<…>from there to railway to Harrar, then, having made a caravan, to the south, to the area between the Somali Peninsula and the lakes of Rudolf, Margarita, Zvay; cover as large a study area as possible.

Together with Gumilyov, his nephew Nikolai Sverchkov went to Africa as a photographer.

First Gumilev went to Odessa, then to Istanbul. In Turkey, the poet showed sympathy and sympathy for the Turks, unlike most Russians. There, Gumilyov met the Turkish consul Mozar Bey, who was on his way to Harar; they continued on their way together. From Istanbul they went to Egypt, from there to Djibouti. Travelers were supposed to go inland by rail, but after 260 kilometers the train stopped due to the fact that the rains washed out the path. Most of the passengers returned, but Gumilyov, Sverchkov and Mozar Bey begged the workers for a trolley and drove 80 kilometers of the damaged track on it. Arriving in Dire Dawa, the poet hired an interpreter and went by caravan to Harar.

Haile Selassie I

In Harrar, Gumilyov bought mules, not without complications, and there he met Ras Tafari (then governor of Harar, later Emperor Haile Selassie I; adherents of Rastafarianism consider him the incarnation of the Lord - Jah). The poet presented the future emperor with a box of vermouth and photographed him, his wife and sister. In Harare, Gumilyov began to collect his collection.

From Harar, the path lay through the little-studied lands of the Gaul to the village of Sheikh Hussein. On the way, they had to cross the fast-flowing Uabi River, where Nikolai Sverchkov was almost dragged away by a crocodile. Soon there were problems with provisions. Gumilyov was forced to hunt for food. When the goal was achieved, the leader and spiritual mentor Sheikh Hussein Aba Muda sent provisions to the expedition and warmly received it. Here is how Gumilyov described the prophet:

Fat ebony recreated on Persian carpets

In a dark, untidy room,

Like an idol, in bracelets, earrings and rings,

Only his eyes sparkled wonderfully.

There Gumilyov was shown the tomb of Saint Sheikh Hussein, after whom the city was named. There was a cave from which, according to legend, a sinner could not get out:

I had to undress<…>and crawl between the stones into a very narrow passage. If someone got stuck, he died in terrible agony: no one dared to lend him a hand, no one dared to give him a piece of bread or a cup of water ...

Gumilyov climbed there and returned safely.

Having written down the life of Sheikh Hussein, the expedition moved to the city of Ginir. Having replenished the collection and collected water in Ginir, the travelers went west, on the hardest path to the village of Matakua.

The further fate of the expedition is unknown, Gumilyov's African diary is interrupted at the word "Road ..." on July 26. According to some reports, on August 11, the exhausted expedition reached the Dera valley, where Gumilyov stayed at the house of the parents of a certain H. Mariam. He treated the mistress of malaria, freed the punished slave, and the parents named their son after him. However, there are chronological inaccuracies in the Abyssinian's story. Be that as it may, Gumilyov safely reached Harar and was already in Djibouti in mid-August, but due to financial difficulties he was stuck there for three weeks. He returned to Russia on September 1.

LISYANSKY Yuri Fedorovich(1773-1837) - Russian navigator and traveler Yu.F. Lisyansky was born on August 2 (13), 1773 in the city of Nizhyn. His father was a priest, archpriest of the Nizhyn church of St. John the Theologian. From childhood, the boy dreamed of the sea and in 1783 he was assigned to the Naval Cadet Corps in St. Petersburg, where he became friends with I.F. Krusenstern.