Sailing ships began to be seen as a significant force in naval combat from around the 1620s. Prior to this, galleys were trendsetters in the navies. It is often claimed that a new tactic at sea, namely the tactics of sailing ships, was used by the British in battles with the Invincible Armada in 1588. To a certain extent, this is hypocrisy. The fact is that the "sea hawks" of Elizabeth of England, in fact, did not demonstrate any tactics.

Tactics of the galley fleet

The two largest naval battles before Thirty Years' War in post-antique Europe, this is the battle of Lepanto and a series of battles with the Invincible Armada. It was these two battles that influenced the further history of the development of naval tactics and even military shipbuilding.

Combined galley front formation with reinforcement

Combined galley front formation with reinforcement

At the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, Christian rowing ships defeated the Muslim rowing fleet. Cannon battle played there, although an important, but a secondary role. The main fights took place during the boarding of ships. Thus, the outcome of this battle was decided by the better weapons of the average Spanish infantryman compared to the average Muslim warrior. The Spaniards, thanks to the saturation of the marines with firearms and heavy armor, simply swept away the boarding parties of the Turks with swords, bows and light defensive weapons.

However, the Spaniards also had a large number of tactics developed for the galleys. The peculiarity of such rowing vessels is that their main artillery is concentrated on the bow. This is what determined the tactics of use. The most popular galley formation is the front formation, convenient for maximum use of artillery. And then there were options.

Various formations of galleys. From left to right - bearing, line, front, rhombus, division of the front into left, right flanks and center

Various formations of galleys. From left to right - bearing, line, front, rhombus, division of the front into left, right flanks and center

For example, sometimes the galleys were built in a wedge to break through the front of the enemy. To strengthen their front so that the enemy could not break through it, columns of galleys were used, which could move either to the left or to the right, in the gaps between the vanguard, and attack the flanks or center of the enemy. At the same time, the galleys located in the rear could create any acceptable formation - bearing, rhombus, front, line. That is, the opportunities for attack were used flexibly, depending on the situation.

Most often, the galleys were divided into fives: the flagship and four galleys attached to it (two on each side). This helped during the battle to solve many tasks by separate units, each of which did not lose control in battle. So, for example, in a battle surrounded by a galley of one five, they became a rhombus in order to repel an attack from any side. The flagship galley was in the center and served as both a command post and a means of reinforcement. Accordingly, the squadrons could use both a simple linear battle formation and reinforce it along the flanks or the center. Naval commanders could combine their formations depending on the opposing forces and change them, if necessary, during the battle.

Various formations of detachments and formations - a concave order, a convex order, a funnel, a wedge, a triangle. Squadron formations - with reinforcement in the center (for a breakthrough) - cross, with a linear distribution of available forces - eagle

Various formations of detachments and formations - a concave order, a convex order, a funnel, a wedge, a triangle. Squadron formations - with reinforcement in the center (for a breakthrough) - cross, with a linear distribution of available forces - eagle

If galleys with unequal weapons were available, the weakly armed ones tried to be evenly distributed between the stronger galleys. Thus, two birds with one stone were killed - it was possible to support weaker ships, and at the same time help stronger ones in the performance of a combat mission. Sometimes, however, all the most powerful galleys were brought together into a single fist, with which, at the climax of the battle, the main blow was delivered, capable of breaking the enemy's resistance.

Victory over the Invincible Armada

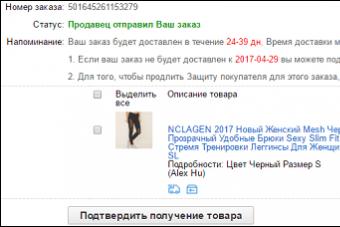

Naturally, the sailors who switched from galleys to sailing ships first transferred the tactics of the galleys to the tactics of the sailing fleet. For example, the formation of the Invincible Armada is a typical formation of a large galley fleet. Let's take a look at it. So, ahead is the vanguard of the most powerful squadrons - Castilian and Portuguese (commanders - Diego de Valdes and Medina Sidonia, respectively). Behind these forces are reinforced by pinnaces, which, in the event of a frontal attack, block the enemy's access to supply ships.

The left flank is slightly pulled back, where the Andalusian Armada of Pedro de Valdes and the Biscay Armada of Recalde are located. By the way, during the campaign of the Spanish fleet, these were his most combat-ready formations. Why were they on the left flank? The answer is simple. The Armada was moving along the Channel, having the British coast on the left, so the decision to place a combat-ready and strong formation on the left flank is quite logical.

Building the Invincible Armada. Distribution of forces by divisions

Building the Invincible Armada. Distribution of forces by divisions

The right flank is also slightly pulled back, here the Gipuzkoan Armada of Oquendo and the Levantine Armada of Bretendon hold the line. If Oquendo's forces can be considered quite combat-ready, then Bretendon's squadron is frankly weak, it consists mainly of chartered merchants. However, the likelihood of an attack from this side is less. In which case, the Mediterraneans can always be supported by transferring the forces of Recalde and Pedro de Valdes to help them. And if you look at all of the above from a bird's eye view, then we will see the standard Spanish formation for the eagle-type galley fleet.

Building the Invincible Armada. General scheme

Building the Invincible Armada. General scheme

Now for the English. A series of battles between the English fleet and the Spanish Invincible Armada from 1 to 10 August 1588 did not reveal the advantages of artillery combat. And this fact, at first glance, seems surprising.

Appointed in 1573 as treasurer and inspector of the Royal Navy, John Hawkins said that, if possible, it is necessary to get away from boarding tactics, to actively use long-range guns, to strive to knock down the rigging and spars of the enemy in order to make him uncontrollable. The new fleet inspector completely rejected the Spanish experience, where only a quarter of the sailors and three-quarters of the soldiers were in the crews. On the contrary, Hawkins proposed to complete the teams mainly with sailors and gunners, and who knew their job perfectly.

But in 1588, this fleet, which had been specially nurtured for 15 years for artillery combat, could neither stop the Spanish Armada nor inflict significant losses on it. In fact, only the steady southwest and Farnese's lack of concentration saved England from invasion and inevitable defeat. It turned out that artillery is still very far from perfect, and its best use for this time is fire at upper deck and rigging in the hope of inflicting significant losses on enemy boarding parties or weakening resistance before capturing the ship.

This does not look so fantastic, if we remember that large-caliber guns then had a short firing range, and a volley from more long-range light guns could not penetrate the side of an enemy ship. On Spanish and Dutch ships, for example, guns larger than 26 pounds in caliber were very rarely seen. And this fully fit into the concept of the auxiliary role of artillery. The task of guns is to shoot quickly, and large calibers required considerable time to reload.

At that time, the British had not developed any special structures for new sailing fleets. They entered the battle whenever possible, sometimes interfering with each other or blocking the sector of fire. At long distances, they broke into threes, and, turning eights, fired at the Spaniards. At the same time, there was still no concept of a broadside, that is, the guns fired on readiness, and most often - where God would send.

Boarding

Boarding

Predictably, the tactics of Hawkins and Drake simply failed. In this way, first conclusion, made from the battles at Lepanto and in the English Channel, was as follows: boarding was and remains the main method of naval combat.

Swarm Tactics

At the same time, battles with the Invincible Armada showed that fast, light, maneuverable ships could easily evade boarding by heavier, but clumsy enemy galleons. Also, they can easily keep a distance at which galleon guns will be ineffective. From here followed second output: in the squadron must be pretty big number small ships, which will either drive away such enemy ships from the main forces, or will themselves attack. It is clear that a one-on-one small ship with a small crew had almost no chance of boarding an enemy ship. From here the naval commanders made one more conclusion: when boarding large ships with small ones, it is necessary to create a local superiority in forces, that is, one large ship should attack three to five small ships.

This is how the "swarm" tactic appeared. . Once again, we note that her "legs" grow precisely from the galley fleet. This is the same “five” of galleys, which are assigned limited tasks, simply transferred to the sailing fleet.

In accordance with the new tactics, ships lined up to attack the enemy, concentrating at the flagships of the divisions. Divisions consisted of three to five ships. The fleet itself was divided into the vanguard, rearguard and center, and the vanguard and rearguard were often used not as the front and rear lines of ships, but along the flanks, as on land "regiment right hand"and" regiment of the left hand. The general management of the battle was present only at the initial stage, then each ship chose its own target. If the enemy had ships of large displacement, then they were attacked by one or two divisions.

The task of the ships of the "swarm" was a quick rapprochement and subsequent boarding. Just like the earlier Zaporizhzhya Cossacks or later the “naval servants” of the rowing fleet of Peter the Great, many small ships stuck around the “leviathans” of the enemy, and from all sides the prize teams landed on the enemy decks.

Fireship launched on the ship

Fireship launched on the ship

But what if the enemy has greater strength than the attacker, or the formation of his ships precludes a "swarm" attack? To destroy the enemy formation and inflict significant losses, they used firewalls- ships loaded with flammable or explosive substances that were used to set fire to and destroy enemy ships. Such a ship could be controlled by a crew that left the ship in the middle of the journey, or rafted downstream or downwind towards the enemy fleet. Torches floating on wooden ships usually completely upset the formation and control of the enemy fleet, which was demonstrated by the attack by the British at Gravelin of the Invincible Armada, where the Spaniards lost all anchors and could no longer take on board the land units of Farnese.

conclusions

Each of the three opposing fleets (English, Dutch, Spanish) learned their lessons from the defeat of the Invincible Armada. The Dutch fleet quickly drew the right conclusions for itself. Lighter ships were loaded with light artillery and equipped with increased crews.

As for the Spaniards, they decided that their heavy galleons with a large number of naval soldiers were a tough nut to crack for any attacker. The galleon for the hidalgo was a universal ocean-going ship, with all its advantages and disadvantages. AND leading role it was their universalism that played in the construction of the galleons, and not their suitability for specific combat missions. Today they could carry cargo to the West Indies, tomorrow they could sail for goods to Manila, the day after tomorrow guns were hoisted on the galleon, and the ship participated in a military expedition to the English Channel, and a few days later the ship, having returned the guns to the Cadiz arsenal, again headed for silver in the West Indies.

Yes, it was a heavy and clumsy ship, but the task of fighting someone else's maritime trade was not set before the galleons. The galleons themselves should have been more afraid of being attacked. Therefore, the speed, taking into account the good armament, they were not really needed.

It is noteworthy that in the Flemish Armada, focused specifically on the fight against Dutch trade and the Dutch fleet, the galleons soon disappeared as a class, and their place was taken by warships (similar to the Dutch and English) and "Dunkirk" frigates (modified flutes with an elongated and narrowed hull and three tiers of sails). Unlike later frigates, the Dunkirks were focused specifically on boarding, having good speed, excellent maneuverability, light armament (most often guns from 8 pounds or less) and an increased crew. Large flocks of these ships became a formidable force in the English Channel and the North Sea, they were almost able to break the Dutch resistance, and only in 1637, after the reorganization of the Dutch fleet, the United Provinces were able to somehow limit the activities of the Flemish corsairs.

As for the British, they temporarily froze their tactical research and returned to the development of new naval battle tactics only in the 1630s.

Battle of Oliva between the fleet of the Commonwealth and the Swedish fleet on November 28, 1627. Carried out by both sides using the standard swarm tactics of the time

Battle of Oliva between the fleet of the Commonwealth and the Swedish fleet on November 28, 1627. Carried out by both sides using the standard swarm tactics of the time

Thus, at the end of the 16th - beginning of the 17th centuries, the main tactic in naval battles remained, as in previous years, boarding. All fleets actively used fireships, and cannon combat was used as an auxiliary means in most of the battles.

From time immemorial, the ships of our ancestors plowed the waters of the Black, Marmara, Mediterranean, Adriatic, Aegean and Baltic Seas, the Arctic Ocean. Russian voyages along the Black Sea in the 9th century were so common that it soon received the name Russian - this is how the Black Sea region is called on Italian maps until the beginning of the 16th century. The Slavic Venice - Dubrovnik, founded by our Slavic ancestors on the shores of the Adriatic Sea, is well known, and the settlements they created on the shores of England are also known. There are accurate data about the campaigns of the Slavs to the island of Crete and Asia Minor, about many other voyages.

In these long-distance voyages, maritime customs developed, gradually forming into maritime regulations and legal provisions.

The first collection of legalizations that determined the order of service on Russian ships appeared under Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich, when the captain of the Oryol ship, the Dutchman D. Butler, submitted a letter to the Ambassadorial Order of the Ship Order, that is, the rules of ship service, also known as Article Articles . This document consisted of 34 articles that defined the duties of the captain and formulated brief instructions to each officer on the ship and in his actions under various circumstances of navigation. "Ship building letter" was a kind of extract from the then Dutch Naval Charter. Most of the articles in this letter were devoted to measures to keep the ship in combat readiness and the tasks of the crew in battle. The duties of the ship's ranks - the captain, helmsman (navigator), boatswain, gunner and others - were defined very harmoniously and clearly. According to this document, the whole team was subordinate to the captain. General duties in battle were regulated by three provisions: “Everyone must stand in his place, where he is ordered, and let no one retreat from his place under great punishment”; “No one dares to turn away from the enemy, and no one dares to dissuade his own people from the battle or to lead people into timidity from the courage”; “If the captain finds it for the good of the enemy to retreat, then everything would be done in order and order.”

The surrender of the ship to the enemy was forbidden unconditionally - the captain took a special oath for this.

Later, a new document appeared in Russia - the Five Maritime Regulations. Its content has not reached our time for certain, as well as information about the date of publication of this, in essence, the Naval Charter. It is known that it was written on the basis of a collection of maritime law called "Oleron Scrolls", or "Oleron Laws" (they were published in France on the island of Oleron in the 12th century), but significantly supplemented and rethought. The "Regulations" also set out the rules of merchant shipping. Part of the "Oleron Laws" was borrowed by the British and in the 15th century included in the legislative maritime code, which had the name "black book of Admiralty" ("Black Book of the Admiralty"). The fact that it was really a “Black Book” is evidenced by at least such legal provisions that determine the penalties for sailors for various misconduct, which are quite consistent with the spirit of the Middle Ages: “1. Anyone who kills another on board a ship must be tied tightly to the slain and thrown into the sea. 2. Anyone who kills another on earth must be tied to the slain and buried in the ground along with the slain. 3. Anyone who draws a knife or other weapon with the intent to strike another must lose his hand. 4. Anyone who is legally accused of stealing should be subjected to the following punishment: the head is shaved and poured with boiling resin, and then sprinkled with feathers to distinguish it from others. At the first opportunity, he should be landed on the shore. 5. Caught sleeping on watch should be hung in a basket to the bowsprit with a mug of beer, a piece of bread and a sharp knife, so that he himself chooses what is best: hang there until he dies of hunger, or cut off the rope attaching the basket and fall into the sea. ..”

I must say that for a long time the punishments in the fleet remained savage.

In England in the 15th century, during the reign of Henry VII, the first law was introduced, formulating the rules for conducting military operations, which acted both on land and at sea. All its most important provisions were written on parchment and attached to the mainmast in a conspicuous place. The team was instructed to read these rules at every opportunity. This is how a strictly enforced custom began to take shape, which later became fixed on the ships of the Russian Navy - reading the Naval Charter to the team on Sundays and public holidays, as well as at the end of the church service and the ceremony of congratulating the crews by the commander or admiral.

When Peter I in 1696 began to create a regular navy of Russia, an instruction “On the order of naval service” appeared, which determined the order of service in galleys. It consisted of 15 articles and contained general regulations and signals on the navigation of the galley fleet, on anchoring and anchoring, on engaging in battle with the enemy and "helping" each other. In almost every article, various penalties were imposed for non-compliance with the prescribed actions, ranging from a monetary fine of one ruble to the death penalty. In 1698, the Russian Vice-Admiral K. Kruys, on behalf of Peter I, compiled a new document - “Rules for Service on Ships”, - the content of which was borrowed from the Dutch and Danish charters and included 63 articles of general decrees on the duties of persons serving on a ship , and the establishment of court procedures with extremely cruel punishments for their violators. The charter of K. Kruys was repeatedly supplemented by decrees of the tsar and private orders of the chiefs of the fleet.

So, in 1707, the charter of K. Kruys was supplemented by the instruction of Admiral F. Apraksin "To the officers who command fireships and bombardment ships, how they should act during an enemy offensive."

In 1710, this charter was revised, taking into account all the changes made, and re-issued under the title "Instructions and Military Articles for the Russian Navy." They also contained 63 articles, similar to the articles of the previous charter. The difference was only in a more complete and definite edition and in the strengthening of punishments. But these "Instructions" did not cover all the activities of the fleet. Work on improving maritime laws and preparing materials for a new version of the naval charter continued. The program of this preparatory work was compiled by Peter I personally. The Tsar Admiral took an active part in writing the Naval Charter itself. According to the memoirs of his associates, he "worked on it sometimes for 14 hours a day." And on April 13, 1720, the document was published under the title "The Book of the Charter of the Sea, about everything related to good governance when the fleet was at sea."

The first Naval Charter in Russia began with the emperor's manifesto, by which Peter I defined the reasons for its publication in the following way: "... this military charter was made so that everyone knew his position and no one would excuse himself with ignorance." This was followed by "Foreword to the willing reader", followed by the text of the oath for those entering the naval service, as well as a list of all ships and fleet units, a list of equipment for ships of various classes.

The naval charter of Peter I consisted of five books.

The first book contained the provisions "On the general-admiral and every commander-in-chief", on the ranks of his headquarters. The document contained articles that determined the tactics of the squadron. These instructions bore a clear imprint of the views of the Dutch admirals of that era and were distinguished by not very strict regulation of the rules and norms that followed from the properties and capabilities of the naval weapons of that time in various conditions of naval combat. Such caution was provided so as not to hamper the initiative of the commanders - this runs through the entire charter as a characteristic feature.

The second book contained regulations on the seniority of ranks, on honors and external distinctions of ships, "on flags and pennants, on lanterns, on salutes and merchant flags ...".

Book Three revealed the organization of the warship and the duties of the officials on it. Articles about the captain (commander of the ship) defined his rights and obligations, and also contained instructions on the tactics of the ship in battle. The latter had the peculiarity that they almost did not concern the tactics of conducting a single battle, providing mainly for the actions of the ship in line with other ships.

Book Four consisted of six chapters: Chapter I - "On Good Conduct on the Ship"; chapter II - “On officer servants, how much anyone should have”; chapter III - "On the distribution of provisions on the ship"; chapter IV - "On awarding": "... so that every employee in the fleet knows and is trustworthy, what service he will be awarded for." This chapter defined rewards for the capture of enemy ships, rewards for the wounded in battle and those who grew old in the service; chapters V and VI - on the division of booty in the capture of enemy ships.

The fifth book - "On Fines" - consisted of XX chapters and was a naval judicial and disciplinary charter. Punishments were distinguished by cruelty, characteristic of the mores of that time. For various offenses, such punishments were provided as “shooting”, keeling (dragging the offender under the bottom of the ship), which, as a rule, ended for the punishable by a painful death, “beating with cats” and so on. “If someone, standing on his watch,” the charter said, “is found sleeping on the way, riding against the enemy, if he is an officer, he will be deprived of his stomach, and the private will be severely punished by cats at the spire .. And if this does not happen under the enemy , then the officer will serve in the privates for one month, and the private will be sent down three times from the rain. Whoever comes to watch drunk, if an officer, then for the first time with a deduction for one month of salary, for another for two, for the third deprivation of rank for a while, or even after consideration of the case; and if a private, he will be punished by beating at the mast. And further: "Any officer during the battle who leaves his ship will be executed by death as a fugitive from the battle."

Forms of ship reporting sheets, the Book of Signals and the Rules of the Sentinel Service were attached to the Maritime Charter.

The maritime charter of Peter I, with minor changes and additions, lasted until 1797 and went through eight editions. In 1797, a new Charter of the Navy was published, which was very different from Peter's. In the sections of tactics, it reflected the views on the conduct of the battle of the then British admirals and was developed in detail.

Over the years, influenced by the improvement of the technical means of the navy and the advent of steam ships, that charter also became obsolete, and in 1850 a committee was formed to prepare a new Naval charter, issued in 1853. Unlike the previous statutes, it did not contain regulations regarding tactics. The Commission considered that this was not the subject of the law. In the charter of 1853, there were practically no regulations on the conduct of battle, as well as the division of the fleet into parts, the rules for compiling ship schedules, and the classification of the ship's artillery.

After 1853, no complete revision of the charter was made. Commissions were appointed three times to revise the Maritime Charter, but their activities were limited to only a partial change in its individual articles - the general spirit of the charter remained unchanged. These were the new editions of the Maritime Charters of 1869-1872, 1885 and 1899.

The sad experience of the Russo-Japanese War showed the inconsistency of the Russian Naval Charter in force at that time with the principles of warfare at sea, and on the eve of the First World War, a new Naval Charter was issued in the Russian Navy. Despite the complete unsuitability of the charter of 1899 in modern conditions, the Naval charter of 1910 almost completely repeated it. Only the descriptions of flags and officials have been changed.

In 1921, already under Soviet rule, the Naval Disciplinary Regulations were introduced, for the most part retaining the general provisions of the Disciplinary Regulations of the Red Army unchanged - only a few changes were made that corresponded to the conditions of service on the ships of the RKKF. In its introductory part it was said: “There must be strict order and conscious discipline in the Red Fleet, supported by the tireless work of the sailors of the navy themselves. Strict order in the fleet is achieved by realizing the importance of the assigned socialist revolution tasks and unity of actions aimed at strengthening them. Among the revolutionaries there should be no negligent and parasites.

At first, this was the only charter of the RKKF, and it contained some sections that, to some extent, also corresponded to the tasks of the Ship Charter, which was absent at that time. Let's say Section I listed the general duties of officers in the Navy; section II was titled "On flagships and flagship staffs"; section III - "On the positions of the ranks of employees on the ship"; section IV - "On the order of service on the ship"; section V - "On inventory courts and ranks of hydrographic exploitation"; section VI - "On honours, salutes and halyards".

And yet this document was not yet a full-fledged Ship Charter for the RKKF. The first Soviet Ship Charter, approved by the People's Commissar for Military and maritime affairs M.V. Frunze, was put into operation on May 25, 1925. It reflected the ideas of protecting the country and increasing the combat capability of the army and navy. The Charter corresponded to the provisions of the first Constitution of the RSFSR. Before the Great Patriotic War, in connection with the development of weapons and technical means of the navy, it was revised and reprinted twice - in 1932 and 1940.

The content of each charter, its spirit reflected the actual state of the navy, the new conditions of armed struggle at sea. It is with these changes that the appearance of the Ship Charters in the following years is connected: 1951, 1959, 1978 and 2001. They are based on the experience of the Great Patriotic War, the emergence of new classes of ships, types of weapons and means of armed struggle at sea, the entry of Navy ships into the oceans, changes in tactics and operational art, the organizational structure of formations and ships, and much more. In order to prepare such an official legal document, painstaking, lengthy work was necessary. So, for example, for the development of KU-78 in 1975, a group of authors was organized, headed by Admiral V.V. Mikhailin (at that time - the commander of the Baltic Fleet). The team of authors included the most authoritative admirals and officers in their field of activity, each with rich experience in naval service. They took the Ship Charter of 1959 with amendments and additions made to it in 1967 and the Charter of the Internal Service of 1975 as the basis for the project.

The draft charter was finalized several times, it was considered and studied in all fleets, flotillas, main departments and services of the Navy, at the Naval Academy, the highest special officer classes. A total of 749 proposals and comments were received. The chapters that underwent the greatest revision were: "Fundamentals of the ship's organization", "Political work on the ship", "Main duties of officials", "Ensuring the survivability of the ship", "Buttermilk". The charter also included a fundamentally new section - "Declaration of alarms on the ship."

Literally every line of the new charter, every word in it, was verified and specified. For example, such a statutory provision as "Frequent abandonment of the ship by the senior assistant commander of the ship is incompatible with the proper performance of his responsible duties" was taken from the supplement to the 1951 charter. In 1959, he was seized, but, as life has shown, unreasonably. Therefore, I had to return to the well-forgotten old again. Well, this is also the way wisdom is gained - through careful sifting of old experience in search of those grains that can be useful today.

The article about the actions of the commander in case of accidents that threaten the ship with death was presented in a completely new way: “... in peacetime, the ship's commander takes measures to land the ship on the nearest shallow; in wartime, off its coast. - acts, as in peacetime, away from its coast - must flood the ship and take measures to prevent it from being raised and restored by the enemy.

Order of the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy Soviet Union No. 10 of January 10, 1978, the charter was put into effect. The requirements of the Ship Charter are strictly obligatory for the personnel of the crews of warships and all persons temporarily staying on them.

Since the introduction of the first Soviet Ship Charter until the publication of KU-78, it was reissued five times, that is, on average, approximately every 12 years. This "shelf life" turned out to be valid for KU-78. At the end of the 1980s, there was again a need for a fundamental revision of some provisions of the current Ship Charter. In 1986, the 2nd edition of KU-78 appeared. However, the rapidly changing environment led to the need to include a large number of additions and changes in the KU-78. The question arose of a radical revision of the existing charter and the issuance of a new one. This work began back in 1989, but due to the collapse of the USSR, the introduction of the new charter was delayed. Only on September 1, 2001, by order of the Civil Code of the Navy No. 350, the new KU-2001 was put into effect. Many sections and separate articles of KU-78 have undergone changes, some of them are given in a completely new interpretation. But common succession in relation to the Petrine statute, of course, has been preserved.

The first Naval Charter of 1720 became, as it were, the foundation for the daily and combat service of the sailors of the then regular Russian Navy, the fleet of the heroic era of Peter the Great. Centuries passed, but the military spirit that pervaded every line of this Russian naval law, the will to win expressed in it, hatred for the enemy and love for the native ship, the inadmissibility of lowering the flag and surrendering to the enemy - literally everything that this historical document was filled with, passed, like a relay race, from one generation of Russian sailors to another. Some provisions of the first Naval Charter turned out to be so vital that they remained almost unchanged throughout the history of the Russian and Soviet Navy. So, in the charter of Peter I in the second book "On Flags and Pennants ..." it is stated: "The weight of Russian military ships should not lower the flag in front of anyone." KU-2001 completely repeats this requirement: "Ships of the Russian Navy under no circumstances lower their flag in front of the enemy, preferring death to surrender to enemies."

Thus, the Maritime Charter not only regulates the internal life and order of service on warships and ships, but in essence it is a code of codified maritime customs and traditions.

To live according to the charter means to follow it in everything, down to the smallest detail. This is especially important for young officers. There is a saying: "The wisdom of people is not proportional to their experience, but their ability to acquire it." Correctly noted! Where else can a sailor, especially a young one, draw naval wisdom, if not from the Ship Charter, which gives an exhaustive answer to almost any question related to service, helps to behave correctly in any situation, organize any entrusted business in such a way as to come to success. Everything in the statute has already been checked and rechecked hundreds of times, including this pattern: if you want to achieve a strict, truly statutory order, read the statute, as they say, from cover to cover. Here it is appropriate to recall the well-known poetic lines: “O lad, living in service, read the charter for the coming dream, and in the morning, rising from sleep, read the charter more intensely.”

F.F. Ushakov, and D.N. Senyavin, and M.P. Lazarev, and P.S. Nakhimov, and G.I. Butakov, and S.O. Makarov, and heroes of the Great Patriotic War. The sailors of today are also guided by it.

The main requirement for the Battle Formation is not only to move on the battlefield, but also to give each ship the opportunity to use its strengths, offensive and defensive, while covering the weak; To do this, each ship must lie on the most favorable heading angle and be at the most advantageous distance from the enemy for the given moment of the battle.

The above requirement can be met in general formation only by ships with the same tactical qualities.

The presence of a weaker ship in the ranks will immediately respond to the strength of everything; This is especially evident in the difference in the speeds of individual ships.

Connecting different types of ships lowers the strength of everything.

If there are two or more brigades of the same type of ships, those can be. deployed in a common Battle Formation if the tactical elements of their weapons are fully coordinated and if such a combination is desirable in the interests of commanding the battle formation.

Combat Formations can be divided into simple and complex.

Those formations are simple in which the ships are extended in one straight line: the formation of the front is when the ships are located on a line perpendicular to the line of the course, i.e. are on each other's beam; wake formation - when the ships are located one after another on the course line, and bearing formation - when they are on a line inclined to their course line at an angle to the right (right flank bearing formation) or to the left (left flank bearing formation). These three formations can be combined by one term - the bearing formation from 0 to 360, with the wake formation corresponding to the bearing formation of 0 and 180 °, and the front formation to the bearing formation of 90 ° and 270 °.

Complex formations are those in which the location of the ships is one broken line, or several straight or broken lines. Such formations are: the wedge formation, the double front formation, the double wake formation, the double bearing formation, the checkerboard formation, the formation of heaps, and so on.

in different historical eras one or another Battle Formation was chosen by naval commanders depending on the tactical properties of the ships and their main weapons in order to use its power.

So, in the days of the galley fleet, the entire strength of which consisted in a ram and bow throwing or firearms, and whose weak side was the oars and rowers located on the sides, almost the only Battle Formation was considered the formation of the front.

The formation of a wake for the galleys was unthinkable. With the advent of the sailing fleet and the invention of onboard cannon ports, the ram lost its significance. 100-120-push appeared. ships, the strength of which consisted in side (traverse) fire, in the complete absence of bow and stern fire.

To stand under the enfilade (longitudinal) fire of the enemy was almost tantamount to defeat. Hence, a completely natural abrupt transition from the former formation of the front of the galleys to the formation of the wake of sailing ships, which was recognized as the only Battle Formation. With the advent of the steam fleet, which again resurrected the importance of the ram and made it possible for a new location of artillery (due to the release of the decks from spars and rigging), the question of the Combat Formation became much more complicated.

Fleets, not bound by the dependence on the direction and strength of the wind, received freedom of maneuver. This era corresponds to the appearance of all those simple and complex systems that were listed above.

An approximate description of these formations is as follows: the wake formation is the main formation for artillery action; front formation - also for ramming and quick rapprochement with the enemy; bearing system - for ramming at an enemy moving to the right or left; the formation of a double wake in a checkerboard pattern (the same as the formation of a wake with reduced intervals) - for better concentration of fire, since the ships of the 2nd line could shoot at the intervals between the ships of the 1st line.

Other complex formations were explained, apparently, by the desire to create reserves for the ships of the 1st line in case of a ram attack.

The abundance of Combat Formations is explained, on the one hand, by the variety of types of ships, and, on the other hand, by the wide-open horizons for battle tactics. The latter could not be established immediately: theoretical considerations required verification by combat experience, and only war could give this experience.

Now that the tactics of squadron combat have been more or less established, they begin to make certain demands on the technique of shipbuilding; Thus, the types of ships required for the battle are established, and with them, the Combat Formations of the ships.

I. For battleships and armored cruisers intended for linear combat, only simple formations with the smallest number of flanks (two) and the most extensive battle front (more than 300 ° shelling of the horizon) are recognized as Battle Formations. The choice of one or the other depends on:

1) on the tactical properties of the ships that make up this brigade (in the sense of the most profitable shelling and the least damage of the brigade),

2) from the tactical speed of the brigade obtained at a given heading angle and comparing it with the same speed of the enemy (in the sense of controlling combat distances),

3) from the goals pursued at the moment by the brigade according to the battle plan and its actual course (in the sense of occupying and holding the given position by the brigade),

4) from other requirements imposed by artillery on maneuvering (in the sense of increasing the accuracy and validity of the artillery fire of the brigade). And finally

5) from the simplicity and convenience of maneuvering and controlling the battle formation.

II. For cruisers performing a wide variety of operations in combat, a definite Battle Formation is not planned; but if they find themselves in the line of battle, then in choosing a Battle Formation, the cruiser brigade is guided by the foregoing, and the considerations of paragraph 3 are of paramount importance.

III. For destroyers, considerations about the Battle Formation follow from the properties of their main weapon - mines and the combat qualities of the destroyers themselves.

In order to minimize visibility and damage to destroyers, apparently, m. b. wedge and heap formations are recommended; but the disadvantages of complex formations - the inconvenience of maneuvering, control and a small angle of fire - encourage these ships to prefer the bearing formation.

Build ships a strictly defined position of ships relative to each other during joint navigation and combat maneuvering. S. to. Distinguish: simple (ships are located on one straight line) and complex (ships line up in several lines, on one broken line or on several circles). Simple S. to. include: the formation of the wake (each ship follows in the wake of the one ahead); bearing formation (the ships are on a line passing at a certain angle to the course of the leading ship); ledge formation (ships follow, retreating to the right or left of the wake of the ahead ship); front formation (ships are located along a line perpendicular to the course). Complex S. to. consist of two or more simple ones. For a complex formation, in addition to the distance between ships in a column, the distance between the columns is also assigned. The following complex S. to. are most often used: the formation of two wake parallel columns, and the ships of the 2nd column are equal to the corresponding ships of the 1st column or are located opposite the middle of the gaps between the ships of the 1st column (the so-called building in a checkerboard pattern ); double front formation, in which the ships are in two parallel lines, each in the formation of the front, and the corresponding ships of the 2nd line go in the wake of the ships of the 1st line or against the middle of the gaps between the ships of the 1st line; wedge formation, in which the ships line up on the sides of the corner, at the top of which is the leading ship. In addition to complex systems built in rectangular coordinates, high-speed ship formations use circular marching formations (orders). The basis of this construction are concentric circles around the center, moving along a given course. Concentric circles spaced at the same distance from each other are assigned serial numbers, starting from the center of the formation (order). The position of each ship in the formation is determined by the number of the circle (distance from the center of the formation) and the direction (bearing) from the center, N. P. Vyunenko.

Great Soviet Encyclopedia. - M.: Soviet Encyclopedia. 1969-1978 .

See what "Build ships" is in other dictionaries:

The established arrangement of ships relative to each other during joint navigation and combat maneuvering. There are: wake formation (simple and complex), bearing formation, ledge formation, front formation (simple and complex), wedge formation, formation ... ... Marine Dictionary

STORY OF SHIPS, a strictly defined location of ships relative to each other during joint navigation and combat maneuvering. There are systems of bearing (the ships are located on a line passing at an angle to the course of the leading ship), the front ... ... encyclopedic Dictionary

A strictly defined arrangement of ships relative to each other during joint navigation and combat maneuvering. There are systems of bearing (ships are located on a line passing at an angle to the course of the lead ship), front (located on ... ... Big Encyclopedic Dictionary

Build ships- the established location of ships relative to each other during joint navigation and combat maneuvering. Basic S. to. | wake (simple and complex), bearing, ledge, front (simple and complex), wedge, reverse wedge ... Dictionary of military terms

Combat formation of ships- COMBAT ORDER OF SHIPS. The main requirement made by B.S. is not only to move to the battlefield, but also to provide each ship with the opportunity to use its strengths, offensive and defensive ... Military Encyclopedia

A formation in which ships are arranged in several lines or on one broken line. Each complex tuning consists of two or more simple tunings, and the elements of the tuning for each line remain the same. For S. S., another distance is introduced ... ... Marine Dictionary

- (Order, formation) established with a known purpose mutual arrangement ships of the same tactical formation relative to each other and the direction of movement during joint maneuvering. Depending on the tasks, S. marching and combat differ ... Marine Dictionary

This term has other meanings, see Build (meanings). Russian infantry in the ranks, in the foreground of the right-flank soldier ... Wikipedia

- ... Wikipedia

This page is an information list. The tables below show the current combat composition of the Russian Navy by fleets, as well as a summary table for the entire Russian Navy as of 2012. ... Wikipedia

Books

- Museum ships of the world, Looped M. B. The memorial warships guide includes more than 670 warships and auxiliary ships from 55 countries that were part of navies, army formations, marine ...

COMBAT ORDER OF SHIPS. The main requirement made by the B.S. is not only to move on the battlefield, but also to provide each ship with the opportunity to use its strengths, offensive and defensive, while covering the weak ones; to do this, each ship d. lie at the most advantageous. course angle and be in the best position. for dan. the moment of the battle the distance from the nepr-la. The above requirement can be satisfied in the general system only by ships with the same tactical. qualities. The presence of a weaker ship in the ranks will immediately respond to the strength of the entire detachment; This is especially evident when there is a difference in the speeds of the stroke. ships. The combination of ships of different types lowers the strength of the entire squad. If there are two or more brigades of the same type of ships, those can be. placed in the general B. S., if tactical. elements of their weapons are fully coordinated, and if such a connection is desirable in the interests of management b. in order. B. S. can be divided into simple and complex. Those simple formations in which the ships are stretched in one straight line: line abreast, - when the ships are located on the line, perpendicular. to the course line, i.e., they are abeam each other; line ahead, - when the ships are located one after another on l. course, and bearing system, - when they are on a line that is inclined to their course line at an angle to the right (bearing formation right flank) or to the left (bearing formation left flank). These three systems can be. united by one term - bearing build from 0 to 360, wherein the wake formation corresponds to the bearing formation of 0 and 180 °, and the front formation corresponds to the bearing formation of 90 ° and 270 °. Complicated build those in which the location of the ships is one broken line, or several. straight. or broken lines. These buildings are: wedge action, system double front, system double wake, system dual bearing, system staggered order, system heaps and so on. In various historical era, one or another B.S. was elected by naval commanders depending on the tactical. properties of ships and their main. weapon in order to use its power. So, in the days of the galley fleet, the whole strength of which consisted in a ram and a bow throwing or firearm. weapons and the weak side of which were oars and rowers located on the sides, the front system was considered almost the only BS. The formation of a wake for the galleys was unthinkable. With the advent of the sailing fleet and the invention of onboard cannon ports, the ram lost its significance. 100-120-push appeared. ships, the strength of which consisted in side (traverse) fire, in the complete absence of bow and stern fire. Standing under enfilade (longitudinal) fire was almost tantamount to defeat. Hence, a completely natural abrupt transition from the previous formation of the front of the galleys to the formation of the wake of sailing ships, which b. recognized as the only B. S. With the advent of the steam fleet, which again resurrected the importance of the ram and made it possible for a new location of artillery. (due to the release of the decks from spars and rigging), the issue of B.S. became much more complicated. Fleets, not bound by the dependence on the direction and strength of the wind, received freedom of maneuver. This era corresponds to the appearance of all those simple and complex systems that were listed above. An approximate description of these formations is as follows: the wake formation is the main formation for artillery action; front line - also for ramming and quick rapprochement with the pr-com; bearing system - for ramming along a avenue moving to the right or left; a double wake formation in a checkerboard pattern (the same as a wake formation with reduced intervals) - for better concentration of fire, since the ships of the 2nd line can shoot at the intervals between the ships of the 1st line. Other complex formations were explained, apparently, by the desire to create reserves for the ships of the 1st line in case of a ram attack. The abundance of BS is explained, on the one hand, by the variety of types of ships, and on the other hand, by the wide-open horizons for battle tactics. The latter could not be established immediately: theoret. considerations required verification b. experience, and this experience can only be given by war. Now that tactics squadron. the battlefield is more or less established, it begins to make certain demands on the technique of shipbuilding; so arr., the types of ships required for battle are established, and with them, together with B. S. I. For lin. ships and armored ships. cruisers, intended. for lin. battle, B.S. only simple formations with a name are recognized. number of flanks (two) and max. extensive b. front (more than 300 ° shelling of the horizon). The choice of this or that system depends: 1) on tactical. properties of the ships that make up the given. brigade (in terms of the angle of the most advantageous shelling and the least damage of the brigade), 2) from the resulting given. course angle tactical. brigade speed and comparing it with the same speed nepr-la (in the sense of control b. distances), 3) from the goals pursued in the given. moment by the brigade according to the battle plan and valid. its course (in the sense of occupying and holding a given position by the brigade), 4) from the rest. Art. to maneuvering (in the sense of increasing the accuracy and effectiveness of the artillery fire of the brigade) and, finally, 5) from the simplicity and convenience of maneuvering and control of B.S. II. For cruisers performing a wide variety of operations in combat, a specific V.S. is not planned; but if they find themselves in the line of battle, then when choosing a BS, the cruiser brigade is guided by the above, and the considerations of paragraph 3 are of paramount importance. III. For destroyers, considerations about B. S. follow from the properties of their main. weapons - mines and b. qualities of the destroyers themselves. For the purposes of hiring visibility and damage to destroyers, apparently, m. b. wedge and heap formations are recommended; but the disadvantages of complex formations - the inconvenience of maneuvering, exercise and a small angle of fire - encourage these ships to prefer the bearing formation.