Great attention L.S. Vygotsky devoted to the study of eidetic memory, as one of the stages in the development of human memory. This memory is characterized by the fact that the child can remember any picture accurately and for a sufficiently long time with the smallest details. This ability is called "eidetic memory". In human phylogeny, this stage of memory development can be correlated with the memory of a primitive person. The natives, for example, can unmistakably recognize the footprint of any animal they know and determine which direction it ran, and these people also perfectly remember the area (topographic memory). For the Indians, for example, it is enough to see a landscape once in order to remember it in the smallest details and not get lost there. Likewise, “Levingston commemorates the outstanding memory of the natives of Africa. He observed it at the messengers of the leaders who carry very long messages over great distances and repeat them word for word ”(LS Vygotsky, AR Luria). Accordingly, they have no written language. In the words of Engels: “a person is used by memory, but does not dominate it,” but rather it takes over him. “She tells him unreal fictions, imaginary images and constructions. She leads him to the creation of mythology, which is often an obstacle to the development of his experience, overshadowing the objective picture of the world with subjective constructions ”(LS Vygotsky, AR Luria).

And, as soon as a person was able to "curb" his memory, becoming its master and creating auxiliary means, he was able to move to a higher stage of development. With the emergence of writing and, a little earlier, a certain symbolism, the development of a more perfect memory began. Initially, mediation took place with the help of improvised means: nicks on sticks or knots on clothes, but these simple techniques later became more sophisticated and complex, for example, quipu used in ancient Peru, in ancient China, Japan and some other countries ... Quipu- These are messages made with knots, which, tied in a specific sequence and in a special way, carry messages. With their help, before the invention of writing, people communicated, shared information and important news. It is the discovery of symbols as a way to simplify memorization that can be considered the evolution of memory. “Claude considers the mnemonic stage to be the first stage in the development of writing. Any sign or object is a means of mnemonic memorization ”(LS Vygotsky, AR Luria).

Research that A.N. Leontiev leads in his article "Development of higher forms of memorization" aimed at proving the development of memorization through the process of mediation.

A.N. Leontiev describes a series of experiments that were carried out on children from 4 to 13 years old and on students. Their essence was as follows: the subjects were dictated words, after the first series, the children simply had to repeat the spoken words, in the second and third series they were offered additional material - picture cards, the content of which did not coincide in any way with the list of dictated words during these sessions.

While listening to a number of words, he was asked to choose a card that, in his opinion, would help to remember a certain word: “When I say a word, look at the cards, choose and put aside a card that will help you remember the word” (AN Leontyev ).

After analyzing the results, several facts became apparent:

Firstly, the third series in children 4-5 years old differs very little from the second (the indicators of the third are slightly higher), but already the next age group of children (6-7 years old) showed higher results, which proves that the rapid development of mediated, logical memory.

Secondly, children from 7 to 12 years old also showed good results, but the rate of development of their memory compared to the previous age group is somewhat lower. The difference between the second and third series becomes less noticeable and, as it were, “smoothed out”.

From this we can draw the following conclusion: “starting from preschool age, the rate of development of memorization with the help of external means significantly exceeds the rate of development without the help of cards” (AN Leontiev).

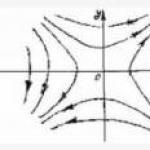

If these changes are presented graphically, the graphical form will be similar to a parallelogram: “Both lines (second and third series) of development are two curves, converging in the lower and upper limits” (AN Leontiev).

In general, this experiment shows how memory develops in the process of growing up, how from eidetic (discussed above) it is transformed into logical through the use of signs-symbols that simplify the memorization process. “Before becoming internal, these stimuli-signs appear in the form of stimuli acting from the outside. Only as a result of a peculiar process of their "rotation" do they turn into internal signs, and thus a higher, "logical" memory grows from the initial direct memorization "(AN Leont'ev).

Details 09 March 2011 Views: 32668- Previous Article Definition and general characteristics of memory

- Next Article Theories and laws of memory (Nemov R.S.)

Customize the font

The concept of memory development by P.P. Blonsky. The theory of cultural and historical development in memory of L.S. Vygotsky. The development of direct and mediated memorization in children according to A.N. Leontiev. The role of speech in managing the development of mnemonic processes. Structural organization of memorized material. Selection and use of effective stimuli-means for memorization and recall. Other tricks to improve memory. Imagination and memory. Mental associations and memorization. The negative role of interference in the reproduction of material.

Let us now turn to the question of the development of memory, i.e. about those typical changes that occur in it as the individual is socialized. From early childhood, the process of developing a child's memory follows several directions. Firstly, mechanical memory gradually supplemented and replaced logical... Secondly, over time, direct memorization turns into mediated, associated with active and conscious use of various mnemonic techniques and means for memorizing and reproducing. Third, involuntary memorization, which dominates in childhood, turns into voluntary in an adult.

IN memory development in general, two genetic lines can be distinguished: its improvement in all civilized people without exception as social progress and its gradual improvement in a single individual in the process of his socialization, familiarization with the material and cultural achievements of mankind.

A significant contribution to the understanding of the phylogenetic development of memory was made by P.P. Blonsky... He expressed and developed the idea that various types of memory presented in an adult are also different stages of its historical development, and they, accordingly, can be considered phylogenetic stages of memory improvement . This refers to the following sequence of types of memory: motor, affective, figurative and logical. P.P. Blonsky expressed and substantiated the idea that in the history of the development of mankind, these types of memory consistently appeared one after another.

In ontogeny, all types of memory are formed in a child quite early and also in a certain sequence. Later than others it folds up and starts to work logical memory , or, as it was sometimes called P.P. Blonsky, "Memory-story". It is already present in a child of 3-4 years of age in relatively elementary forms, but it reaches a normal level of development only in adolescence and adolescence. Its improvement and further improvement are associated with teaching a person the basics of science.

Start figurative memory associated with the second year of life, and it is believed that this type of memory reaches its highest point only by adolescence. Earlier than others, about 6 months of age, begins to manifest itself affective memory , and the very first in time is motor , or motor , memory. Genetically, it precedes everything else. So thought P.P. Blonsky.

However, many data, in particular facts testifying to a very early ontogenetic emotional response of the infant to the mother's appeal, suggest that, apparently, affective rather than motor memory begins to function earlier than others. It may well be that they appear and develop almost simultaneously. In any case, a final answer to this question has not yet been received.

Considered the historical development of human memory from a slightly different angle L.S. Vygotsky... He believed that the improvement of human memory in phylogenesis proceeded mainly along the line improving the means of memorization and changing the connections of the mnemonic function with other mental processes and human states. Historically developing, enriching his material and spiritual culture, man has developed more and more perfect means of memorization, the most important of which is writing. (During the XX century, after leaving L.S. Vygotsky from life, many other, very effective means of memorizing and storing information were added to them, especially in connection with scientific and technological progress.) Thanks to various forms of speech - oral, written, external, internal - a person was able to subordinate memory to his will, reasonably control memorization progress, manage the process of storing and reproducing information.

Memory, as it developed, came closer and closer to thinking. "Analysis shows, - wrote L.S. Vygotsky- that a child's thinking is largely determined by his memory ... Thinking for a child of an early age means remembering ... Thinking never reveals such a correlation with memory as at a very early age. Thinking here develops in direct dependence on memory ”1. Investigation of the forms of underdeveloped children's thinking, on the other hand, reveals that they represent a recollection of one particular incident, similar to an incident that took place in the past.

Decisive events in a person's life, changing the relationship between memory and his other psychological processes, occur closer to adolescence, and in their content, these changes are sometimes opposite to those that existed between memory and mental processes in the early years. For example, the attitude "to think is to remember" with age is replaced by the child's attitude, according to which memorization itself is reduced to thinking: "to remember or remember is to understand, comprehend, and comprehend."

---------

1 Vygotsky L.S. Memory and its development in childhood // Reader in general psychology: Psychology of memory. - M., 1979 .-- S. 161.

Special studies of direct and indirect memorization in childhood were carried out by A. N. Leontiev... He experimentally showed how one mnemonic process - direct memorization - with age is gradually replaced by another, mediated. This is due to the child's assimilation of more perfect stimuli-means of memorizing and reproducing material. The role of mnemonic means in improving memory, according to A. N. Leontieva, consists in the fact that “turning to the use of auxiliary means, we thereby change the fundamental structure of our act of memorization; formerly direct, direct our memorization becomes mediated " one .

The very development of stimuli-means for memorization obeys the following pattern: at first they act as external (for example, tying knots for memory, using various objects, notches, fingers, etc. for memorization), and then they become internal (feeling, association, representation, image, thought).

In the formation of internal means of memorization, speech plays a central role. “It can be assumed,” notes A. N. Leont'ev, “that the very transition from externally mediated memorization to memorization, internally mediated, is in the closest connection with the transformation of speech from a purely external function into an internal function” 2.

Based on experiments conducted with children of different ages and with students as subjects, A. N. Leontiev deduced the curve of the development of direct and mediated memorization, shown in Fig. 47. This curve, called the "parallelogram of memory development", shows that preschoolers' direct memorization improves with age, and its development is faster than the development of mediated memorization. In parallel with this, the gap in the productivity of these types of memorization is increasing in favor of the former.

-----

1 Leontiev A.N. Development of higher forms of memorization // Reader in general psychology: Psychology of memory. - M., 1979 .-- P. 166.2 Ibid. - S. 167.

Fig. 47. Development of direct (upper curve) and mediated (lower curve) memorization in children and adolescents (according to A. N. Leontiev)

Starting from school age, there is a process of simultaneous development of direct and mediated memorization, and then a more rapid improvement of mediated memory. With age, both curves show a tendency to converge, since mediated memorization, developing at a faster pace, soon catches up with the direct one in productivity and, if we hypothetically continue further the ones shown in Fig. 47 curves should eventually overtake him. The latter assumption is supported by the fact that adults who systematically engage in mental work and, therefore, constantly exercise their mediated memory, if desired and with appropriate mental work, can very easily memorize material, while possessing at the same time a surprisingly weak mechanical memory.

If in preschoolers memorization, as the curves under consideration testify, is mainly direct, in an adult it is mainly (and perhaps even exclusively due to the above assumption) mediated.

Speech plays an essential role in the development of memory, therefore the process of improving a person's memory goes hand in hand with the development of his speech.

Let's summarize what has been said about memory in this chapter, and at the same time try to formulate some practical recommendations for improving memory based on the material presented here.

The last of the facts we have noted - about the special role that speech plays in the processes of memorization and reproduction - makes it possible to draw the following conclusions:

1. What we can express in words is usually easier and better remembered than what can only be perceived visually or aurally. If, in addition, words do not simply act as a verbal substitute for the perceived material, but are the result of its comprehension, i.e. if the word is not a name, but a concept containing an essential thought associated with the object, then such memorization is the most productive. The more we think about the material, the more actively we try to present it visually and express it in words, the easier and more firmly it is remembered.

2. If the subject of memorization is a text, then the presence of pre-thought out and clearly formulated questions to it, the answers to which can be found in the process of reading the text, contributes to its better memorization. In this case, the text in memory is stored longer and more accurately reproduced than when questions are posed to it after reading it.

3. Preservation and recall as mnemonic processes have their own characteristics. Many cases of forgetting associated with long-term memory are explained not so much by the fact that the material being reproduced was not properly memorized, but by the fact that it was difficult to access during recall. A person's poor memory may have more to do with difficulty remembering than remembering as such. Trying to remember something, to extract it at the right moment from long-term memory, which usually stores a colossal amount of information, is analogous to searching for a small book in a huge library or a quotation in a collection of essays numbering dozens of volumes. The failure to find a book or a quote in this case may be related not to the fact that they are not at all in the appropriate repositories, but to the fact that we may be looking for them in the wrong place, and not in the right way. The most illustrative examples of successful recall are provided by hypnosis. Under his influence, a person can unexpectedly recall long-forgotten events of distant childhood, the impressions of which, it would seem, are forever lost.

4. If two groups of people are asked to memorize the same list of words that can be grouped by meaning, and if, in addition, both groups of people are provided with different generalizing words-stimuli, with the help of which it is possible to facilitate recall, then it turns out that each of them is able to will remember more precisely those words that are associated with the stimulus words offered to her.

The richer and more diverse the stimuli-means that we have for memorizing, the simpler and more accessible they are for us at the right moment in time, the better voluntary recall. In addition, two factors increase the likelihood of successful recall: the correct organization of the memorized information and the provision during its reproduction of such psychological conditions that are identical to those in which the memorization of the corresponding material took place.

5. The more mental efforts we make to organize information, to give it a holistic, meaningful structure, the easier it is later to remember. One of the most effective ways to structure memorization is to give the memorized material a tree structure (Fig. 48). Such structures are widespread wherever it is necessary to concisely and concisely present a large amount of information.

The organization of memorized material into structures of this kind contributes to its better reproduction because it greatly facilitates the subsequent search for the necessary information in the “storerooms” of long-term memory, and this search requires a system of thoughtful, economical actions that will certainly lead to the desired result. With the preliminary structural organization of the memorized material, along with it, the very scheme with the help of which the material was organized is laid in long-term memory. When reproducing it, we can use this scheme as a ready-made one. Otherwise, it would have to be created and constructed anew, since the memory also occurs according to schemes.

Fig. 48. The semantic structure of the organization of material according to the type of "tree", most widely used in a variety of "repositories" of information

Currently, a considerable number of various systems and methods of practical influence on human memory have been developed and are being used in practice in order to improve it. Some of these methods are based on the regulation of attention, others involve the improvement of the perception of material, others are based on the exercise of the imagination, the fourth - on the development of a person's ability to comprehend and structure the memorized material, the fifth - on the acquisition and active use of special mnemonic means in the processes of memorizing and reproducing, techniques and actions. All these methods are ultimately based on the facts established in scientific research and confirmed by life facts of the connection of memory with other mental processes of a person and his practical activity.

6. Since memorization directly depends on attention to the material, any techniques that allow you to control attention can also be useful for memorization. This, in particular, is based on one of the ways to improve memorization of educational material by preschoolers and younger schoolchildren, which they try to make this way so that it arouses involuntary interest from students, attracts their attention.

7. Remembrance of the material is also influenced by the emotions associated with it, and, depending on the specifics of the emotional experiences associated with memory, this influence can manifest itself in different ways. We think more about situations that have left a bright, emotional mark in our memory than about emotionally neutral events. We organize the impressions connected with them better in our memory, more and more often we correlate with others. Positive emotions tend to promote recall, while negative ones discourage.

8. Emotional states accompanying the memorization process are part of the situation imprinted in the memory; therefore, when they are reproduced, then by association with them the whole situation is restored in the representations, and recollection is facilitated. It has been experimentally proven that if at the moment of memorization a person is in an elevated or depressed mood, then the artificial restoration of his corresponding emotional state during recall improves memory.

9. On the technique of improving the perception of the material, various methods of teaching the so-called "accelerated" reading are based. A person is taught here to quickly discover the most important in the text and to perceive mainly this, deliberately skipping everything else. To a large extent, such learning, and, consequently, the improvement of memorization can be helped by psycholinguistic knowledge about the semantic structure of texts.

10. It has been shown that imagination can be controlled. With thoughtful and systematic exercises, it becomes easier for a person to imagine what is visible in his imagination. And since the ability to visually represent something positively affects memorization, the techniques aimed at developing the imagination in children simultaneously serve to improve their figurative memory, as well as accelerate the process of transferring information from short-term and operative memory to long-term memory.

11. The habit of meaningfully comprehending the material is also associated with improved memory. Exercises and assignments for understanding various texts and drawing up plans for them are especially beneficial in improving the memory of students. The use of notes (for example, shorthand), drawing up diagrams of various objects in order to memorize them, creating a certain environment - all these are examples of the use of various mnemonic means. Their choice is due to the individual characteristics and personal capabilities of a person. It is best for a person to rely on what is most developed for him in improving his memory: sight, hearing, touch, movement, etc.

Let's consider some specific techniques for improving memory that could be used by any person, regardless of how developed his individual mental functions and abilities. One of them is based on more active use of figurative thinking and imagination when memorizing and reproducing material. In order to remember something quickly and for a long time, it is recommended to perform the following sequence of actions in relation to the material:

A. Mentally associate the memorized with some well-known and easily imagined subject. This subject is further associated with some other, which will be at hand just when you need to remember the memorized.

B. In the imagination, combine both objects with each other in a bizarre way into a single, fantastic object.

B. Mentally imagine how this item will look like.

These three actions are practically enough to recall the memorized at the right time, and thanks to the actions described above, it is immediately transferred from short-term memory to long-term memory and remains there for a long time.

For example, we need to remember (do not forget to complete) the following series of things: call someone, send a written letter, borrow a book from the library, go to the laundry, buy a train ticket (this row can be quite large - up to 20-30 and more than units). Suppose also that it is necessary to make sure that we remember the next task immediately after the previous one has been completed. To make this happen, we will proceed as follows. For each case, we will come up with some familiar, easily imaginable, meaning-related object that will surely catch our eye at the right time and in the right place. In accordance with the above series of cases, such items can be the following: telephone receiver, mailbox, book, laundry bag, money.

Now we act in accordance with the second and third of the rules formulated above: we connect the listed objects in pairs with each other in unusual associations and mentally imagine what we have invented. The first such item could be, for example, a mailbox made in the form of a telephone receiver; the second - a huge mailbox filled with books; the third - a long arm wrapped in linen; the fourth - huge banknotes, stacked and tied in the form of a linen bundle. After this procedure, it is enough to consistently imagine how the objects invented by us will look like, so that at the right time, when these objects catch our eye, remember the affairs associated with them.

There is one technique to keep in mind, based on the formation of associations. If, for example, it is necessary to memorize a text, or a proof of a theorem, or any foreign words as best as possible, then you can proceed as follows. Set yourself the additional task of finding an answer to the questions: “What does this remind me of? What does it look like?"

Further reading the text or the proof of the theorem, we will have to answer the following specific questions: “What other text or episode from my life reminds me of this text? What other proof resembles the way of proving this theorem? " Getting acquainted with a new word, we must immediately mentally answer such, for example, a question: "What other word or event reminds me of this word?"

The following regularity is at work here: the more various associations the material evokes upon first acquaintance with it, and the more time we devote to mentally working out these associations, the better the material itself is remembered.

The basic principle underlying many mnemonic techniques is the use of images that connect the memorized material with a sign, or the formation of such connections within the memorized material itself. In order to well remember the sequence of unrelated words, it is enough to do the following. Imagine the path that we go through every day, going to school or to work. Consecutively passing through it in the mind, "arrange" along the way that which needs to be remembered in the form of objects associated with the memorized in meaning. Once we have done this kind of work, then, following this path, we will be able to remember everything we need. It will be enough for this even to simply imagine the appropriate path.

An important means of improving memory, as the studies of Russian psychologists have shown, can be the formation of special mnemonic actions, as a result of mastering which a person is able to better remember the material offered to him due to a special, conscious organization of the process of his cognition in order to memorize. The development of such actions in a child, as shown by special studies, goes through three main stages. At the first stage (younger preschoolers), the child's mnemonic cognitive actions are organized by an adult in all essential details. At the second stage, older preschoolers are already able to independently classify, distribute objects based on common characteristics into groups, and the corresponding actions are performed in an external expanded form. At the third stage (junior schoolchildren), complete mastery of the structure and performance of cognitive mnemonic actions in the mind is observed.

For better memorization of the material, it is recommended to repeat it shortly before the normal bedtime. In this case, what is remembered will be better stored in memory, since it will not mix with other impressions, which usually overlap each other during the day and thereby interfere with memorization, distracting our attention.

However, in connection with this and other recommendations for improving memory, including those mentioned above, it should be remembered that any techniques are good only when they are suitable for a given person, when he chose them for himself, invented or adapted, based on their own tastes and life experience.

The efficiency of memorization is sometimes reduced by interference, i.e. mixing one information with another, some schemes of remembering with others. Most often, interference occurs when the same memories are associated in memory with the same events and their appearance in consciousness gives rise to the simultaneous recall of competing (interfering) events. Interference often occurs when, instead of one material, another is learned, especially at the stage of memorization, where the first material has not yet been forgotten, and the second is not learned well enough, for example, when words of a foreign language are memorized, some of which have not yet been deposited in long-term memory, but others are just beginning to be studied at the same time.

Nemov R.S. Psychology: Textbook. for stud. higher. ped. study. institutions: In 3 books. - 4th ed. - M .: Humanit. ed. center VLADOS, 2003. - Book. 1: General Foundations of Psychology. - 688 p. S. 243-254.

There is no single definition of memory in psychology. Memory - it is the subject's ability to preserve certain contents for some time, which are the results of memorization processes, which can be judged by the results of the processes of updating these contents.

Types: motor, affective, figurative, verbal and logical (Blonsky). Autobiographical memory, which includes images of memories in which episodes associated with significant events of a person that determined his life path are captured. (Squier) - procedural, declarative. (Tulving) - semantic, episodic. Explicit, implicit.

Depending on the storage time of information, there are: - ultrashort (for 1-2 sec.); - short-term (20-30 sec); - long-term (unlimited time).

Memorization processes: voluntary (there is a conscious goal) and involuntary - there is no goal to memorize the material, but memorization still occurs. Processes of updating the stored contents: reproduction - a process as a result of which the stored contents can be updated again in the form of images; recognition is a process as a result of which a person perceives certain contents of conscious experience as already known to him.

Memory functions: understanding of time and the ability to navigate in it; the possibility of learning; the possibility of personal identity.

Amnesia is memory loss. It occurs as a result of brain trauma or concussion, cerebral hemorrhage, stress, etc. Types of amnesia: general; private. General amnesias are: complete, incomplete, temporary, permanent, intermittent, progressive (according to the law of regression or reverse development), retrograde, anterograde, anteroretrograde + Korsakov syndrome. There are also deceptions of memory: paramnesia, confabulation, cryptomnesia.

Association approach (associations- the connection between the phenomena of the psyche or behavior under certain conditions). The following conditions can be used: proximity of associated phenomena in space; or in time; the presence of similarities between them; or contrasting difference. Ebbinghouse the following methods were developed on the basis of meaningless material: memorization; anticipation; saving; recognition. Results: Using such material and methods, Ebbinghaus deduced a number of regularities: the volume of short-term memory is on average 6-7 elements for meaningless syllables; meaningful and well-structured material is better remembered than meaningless material; edge effect: the elements of a row located at its edges are better remembered than those in the middle. Yost established the influence of distribution. Ebbinghaus identified the pattern of forgetting memorized meaningless material by plotting a forgetting curve (using the savings method). Pieron showed that the process of forgetting meaningless material essentially depends on the organization of the process of memorizing it. The phenomenon of reminescence was discovered, which contradicts the results of Ebbinghaus. Reminescence is the opposite of forgetting, in which the subject over time improves the efficiency of reproducing previously memorized material (Ballard's experiment).

Bartlett (constructivist approach) studies of memory in everyday life. sequential memorization procedures (playing with a damaged phone). Most of the information is not remembered; generalization is growing; new elements appear.

Activity approach - the problem of involuntary memorization. Zinchenko experiment, testing the hypothesis that a person involuntarily remembers in b about to a greater extent, the material that is associated with the direction of his activities. A set of cards for classifying items or ordering numbers. Smirnov - latecomers.

Freud reluctance motive. It is found out using the method of free associations.

Levin with iterative memorization of material, forgetting of intentions.

Smirnov- mnemonic orientation (unconscious attitude, not a goal). Unconscious arises when a person performs some kind of activity, which, in order to achieve the desired result, unconsciously involves memorizing a certain material. Experiment by Istomina, the subjects are children, 3 different conditions for completing the task (motivation is different).

Development of memory and attention.

Memory. Vygotsky - in the context of the theory of the historical development of the psyche and human behavior. The central concept is the concept of HMF, which only a person has. Vygotsky indicates 4 properties of the HMF: mediated; social; arbitrary; systemic.

The process of transition of interpsychic function into intrapsychic function is interiorization.

From the standpoint of the cultural-historical theory, the development of memory is considered by Vygotsky as the development of one of many HMFs and occurs according to certain laws that are universal for all functions. This approach was used as the basis for A. N. Leontiev research on the development of memory in ontogenesis. Subjects - children from 4 to 16 years old and adults - students 22-28 years old.

In series 1, a series of 15 words with an interval of 3 seconds was offered for memorization. After 1-2 minutes. after presentation, they were asked to reproduce this series. For each, the number of words played was counted. In series 2, 20 picture cards were given. Then the same row of 15 words was presented and after 1-2 minutes. the experimenter showed the card, and the subject had to name the word that he remembered. The number of correctly reproduced words was counted. As in the method of Vygotsokgo-Sakharov, in the method of Leontiev there were two series of stimuli: stimuli-objects, stimuli-means - the technique of double stimulation.

Main results: 1. For preschoolers in both series, the productivity of memorization turned out to be approximately the same (they still do not know how to use cards as means); 2. In schoolchildren under 12 years of age, there is a maximum difference in the results of the two series (a clear advantage of externally mediated memorization in comparison with natural memorization); 3. In adults, the productivity of memorization in both series increases, but especially in the series without cards. Subjective reports showed that in episode 1 they often used internal means to memorize words. Conclusion: the development of human memory obeys the general law of development of HMF, according to which "the development of higher significative forms of memory goes along the line of externally mediated memorization into internally mediated memorization."

Attention. Vygotsky - the development of attention in the context of the general theory of HMF and the development of attention obeys certain universal laws of the development of HMF. Leontiev conducted research on the material of attention in order to find empirical support for Vygotsky's concept of the laws of development of the HMF. The subjects were children from 4 to 16 years old and adults from 22 to 28 years old. In episode 1, a game of "questions and answers" as a child's game (yes, no, do not say, do not buy black and white). Questions were asked, some of which suggested the name of the flowers. The subjects had to answer as quickly as possible without thinking. However, they did not have to name two specific colors and one color twice. Among the questions were 7 provocative, aimed at violating these two points of the instruction. Episode 2 contains 8 colored cards that could be used to achieve success. Main results: 1. Preschoolers in both series have approximately the same low indicators of task performance efficiency. They still do not know how to successfully concentrate and retain their attention on the execution of the instruction; they do not use cards as useful tools for solving the problem, but simply play with them; 2. For schoolchildren under 12 years of age, the greatest difference is in the two series. They actively use answer cards, putting aside the forbidden colors and those already named. This allows you to better focus and maintain attention on the instructions; 3. In adult subjects, the performance indicators of the task are maximal and they approach each other. They do not use cards, because they no longer need external means of memorization. They have sufficiently developed internally mediated memorization and hence internally mediated attention.

Halperin attention is an independent form of mental activity that performs the function of mental and abbreviated control over the progress of any mental action. Halperin's concept of the stage-by-stage formation of mental actions for the purposeful formation of human attention. Research Kabylnitskaya. A certain understandable plan for working on mistakes - 7 points, which was written down on cards. The card acts as an external means of organizing the child's activities. Thanks to the plan, control over the implementation of activities becomes external and expanded. At first, the children no longer held the card, but pronounced the points aloud, then pronounced the points in a whisper, then a speech to themselves, at the end work on mistakes in the inner plan.

Studying the memory of a cultured person, we, in fact, do not study an isolated "mnemonic function" - we study the entire strategy, all the technique of a cultured person, aimed at consolidating his experience and developed during his own cultural maturation.

L.S.Vygotsky.

We will begin to consider the problem of memory development within the framework of cultural-historical psychology - a discipline that studies the role of culture in mental life. Cultural-historical psychology, of which Vygotsky is a representative in Russian psychology, is focused on the global problem of the role of culture in mental development both in phylogenesis (anthropogenesis and subsequent history) and in ontogenesis.

L.S. Vygotsky writes: "The historical development of memory begins from the moment when a person passes for the first time from using his memory as a natural force to dominating it."

At first glance, it seems absurd to claim that a person is capable of not dominate your memory. However, the studies carried out by M. Cole, J. Glick and others, aimed at studying the memory of the representatives of the African tribe Kpelle, showed that they could not control their memory, did not own it.

Representatives of the Kpelle tribe could, firstly, understand both complex and categorical generalizations, and secondly, they could reproduce material using such generalizations. But at the same time, they could not independently organize the memorized material in a form convenient for them, despite the fact that, under the guidance of the experimenters, they were able to both group elements in accordance with situational generalizations and use their own conceptual categories.

Within the framework of the cultural-historical approach, the process of memory development is considered as a transition from direct (natural) memory, inherent in animals and small children, to arbitrarily regulated, mediated by signs, specifically human forms of memory.

Vygotsky suggested the existence of two lines of development of the psyche - natural and culturally mediated. In accordance with these two lines of development, natural and higher mental functions are distinguished.

The involuntary memory of a child or a savage is an example of natural, or natural, mental functions. The child cannot control his memory: he remembers what is “remembered”. Natural mental functions are a kind of rudiments from which higher mental functions are formed in the process of socialization, and in our case, voluntary memory. The transformation of natural mental functions into higher ones occurs through the mastery of special tools of the psyche - signs, and is cultural in nature.

Speech plays the leading role among the “psychological tools”. Therefore, speech mediation of higher mental functions is the most universal way of their formation.

The main characteristics of higher mental functions - mediation, awareness, arbitrariness - are systemic qualities that characterize these functions as “psychological systems” (as defined by LS Vygotsky), which are created by building new formations over old ones while preserving the latter in the form of subordinate structures inside a new whole.

The regularity of the formation of higher mental functions is that initially they exist as a form of interaction between people (i.e., as an interpsychological process) and only later as a completely internal (intrapsychological) process. As the higher mental functions are formed, the external means of performing the function are transformed into internal, psychological ones (interiorization). In the process of development, higher mental functions are gradually “curtailed” and automated. At the first stages of formation, higher mental functions represent an expanded form of objective activity, which relies on relatively elementary sensory and motor processes; then these actions and processes "roll up", acquiring the character of automated mental actions.

As a result, from immediate, natural, involuntary mental functions become mediated sign systems, social, conscious and voluntary.

Thus, “Cultural development consists in the assimilation of such methods of behavior, which are based on the use of signs as a means for the implementation of a particular psychological operation, in the mastery of such auxiliary means of behavior that mankind has created in the process of its historical development, and what language is, letter, number system, etc. " ,

In discussing the problem of memory, we have a number of discussions, a clash of different opinions, and not only in terms of general philosophical views, but also in terms of purely factual and theoretical research.

The main line of struggle goes here primarily between atomistic and structural views. Memory was a favorite chapter, which in associative psychology was laid at the basis of all psychology: after all, from the point of view of association, perception, and memory, and will were considered. In other words, this psychology tried to extend the laws of memory to all other phenomena and make the doctrine of memory a central point in all psychology. Structural psychology could not attack associative positions in the field of the doctrine of memory, and it is clear that in the early years the struggle between structural and atomistic directions unfolded in relation to the doctrine of perception, and only recent years have brought a number of studies of a practical and theoretical nature in which structural psychology tries break up the associative doctrine of memory.

The first thing that they tried to prove in these studies is that memorization and memory activity obey the same structural laws that also obey perception.

Many remember the report of Gottstald, which was made in Moscow at the Institute of Psychology, and after which he published a special part of his work. This researcher presented various combinations of figures for so long that these figures were assimilated by the subjects without error. But where the same figure met in a more complex structure, the subject who saw this structure for the first time remembered it rather than the one who saw parts of this structure 500 times. And when this structure appeared in a new combination, then what he had seen many hundreds of times was reduced to nothing, and the subject could not separate from this structure the part he knew well. Following the paths of Koehler, Gottstald showed that the very combination of visual images or a reminder depends on the structural laws of mental activity, that is, on the whole in which we see this or that image or its element ... On the other hand, research K. Levin, who grew out of the study of memorizing meaningless syllables, showed that meaningless material is memorized with the greatest difficulty precisely because a structure is formed between its elements with extreme difficulty and that it is not possible to establish structural correspondence in memorizing parts. The success of memory depends on what structure the material forms in the mind of the subject, who memorizes individual parts.

Other work has shifted the study of memory activity into new areas. Of these, I will mention only two studies that are needed to formulate some of the problems.

The first, belonging to B. Zeigarnik, concerns the memorization of completed and unfinished actions and, along with this, both finished and unfinished figures. It consists in the fact that we offer the subject to do several actions in a disorder, and we let him complete some actions, and interrupt others before they end. It turns out that interrupted unfinished actions are remembered by the subjects two times better than completed actions, while in experiments with perception, the opposite is true: unfinished visual images are remembered worse than finished ones. In other words, remembering your own actions and remembering visual images are subject to different laws. There is only one step from here to the most interesting studies of structural psychology in the field of memory, which are covered in the problem of forgetting intentions. The fact is that any intentions that we form require the participation of our memory. If I have decided to do something tonight, then I must remember what I must do. According to the famous expression of Spinoza, the soul cannot do anything according to its decision if it does not remember what needs to be done: "Intention is memory."

And so, studying the influence of memory on our future, these researchers were able to show that the laws of memorization appear in a new form in memorizing completed and unfinished actions in comparison with memorizing verbal and any other material. In other words, structural studies have shown the diversity of various types of memory activity and their irreducibility to one general law, and in particular to the associative law.

These studies were widely supported by other followers.

As you know, K. Buhler did the following: he reproduced in relation to thought the experience that associative psychology poses with memorizing meaningless syllables, words, etc. He compiled a series of thoughts, and each thought also had a second corresponding thought: the first member of this pair and the second member of this pair was given at random. Memorization has shown that thoughts are easier to remember than meaningless material. It turned out that 20 pairs of thoughts for the average person engaged in mental work are memorized extremely easily, while 6 pairs of meaningless syllables turn out to be overwhelming material. Apparently, thoughts move according to other laws than representations, and their memorization occurs according to the laws of the semantic assignment of one thought to another.

Another fact points to the same phenomenon: I mean the fact that we remember the meaning independently of the words. For example, in today's lecture I have to convey the content of a whole series of books, reports, and now I remember the meaning well, the content of this, but at the same time I would have found it difficult to reproduce the verbal forms of all this.

This "independence of memorization of meaning from verbal presentation was the second fact to which a number of studies come. These positions were confirmed by other experimentally obtained facts from zoopsychology. Thorndike established that there are two types of memorization: the first type, when the error curve falls slowly and gradually, that shows that the animal learns the material gradually, and another type, when the error curve falls immediately. However, Thorndike considered the second type of memorization rather as an exception than as a rule. On the contrary, Kohler drew attention to just this type of memorization - intellectual memorization, memorization immediately. This experience has shown that when dealing with memory in this form, we can get two different types of memory activity.Every teacher knows that there is material that is memorized immediately: after all, nowhere has anyone ever tried to memorize solutions to arithmetic problems. the course of the solution in order to be able to do this task in the future decide. Similarly, the study of a geometric theorem is not based on what the study of Latin exceptions, the study of poems or grammatical rules is based on. This is the difference in memory when we are dealing with memorizing thoughts, that is, memorizing meaningful material, and with the activity of memory in relation to memorizing non-meaningful material, this contradiction in various branches of research began to appear for us with greater and greater clarity. ... In the same way as the revision of the problem of memory in structural psychology, so those experiments that came from different sides and which I will talk about at the end gave us such tremendous material that presented us with a completely new state of affairs.

Modern factual knowledge poses the problem of memory in a completely different way than, for example, Bleuler posed it; hence an attempt to communicate these facts arises, to move them to a new place.

I think we will not be mistaken if we say that the central factor in which a whole range of knowledge, both theoretical and factual, about memory is concentrated, is the problem of the development of memory.

Nowhere is this question more confusing than here. On the one hand, memory is already available at a very early age. At this time, memory, if it develops, then in some hidden way. Psychological research has not provided any guiding thread for analyzing the development of this memory; As a result, both in a philosophical debate and in practice, a number of memory problems were posed metaphysically, Buhler thinks that thoughts are remembered differently than representations, but research has shown that a child remembers a representation better than thoughts. A whole series of studies shakes the metaphysical ground on which these teachings are built, in particular, in the question of the development of children's memory that interests us. You know that the question of memory has given rise to great controversies in psychology. Some psychologists argue that memory does not develop, but turns out to be maximum at the very beginning of childhood development. I will not expound this theory in detail, for a number of observations really show that memory turns out to be extremely strong at an early age and as the child develops, memory becomes weaker and weaker.

Suffice it to recall how much work it takes to learn a foreign language for some of us and with what ease a child learns a particular foreign language, to see that in this respect, an early age is, as it were, created for learning languages. In America and Germany, experiments of a pedagogical nature have been made in relation to the transfer of language learning from secondary school to preschool. The Leipzig results showed that two years of preschool education yields significantly more results than seven years of teaching the same language in high school. The effectiveness of the acquisition of a foreign language increases as we shift the study to an early age. We are only fluent in the language that we knew in early childhood. It is worth pondering this to see that an early child has an advantage in language proficiency over an older child. In particular, the practice of upbringing with the instillation of several foreign languages in a child in early childhood has shown that mastering two or three languages does not slow down the mastery of each of them separately. There is a famous study of the Serb Pavlovic, who experimented on his own children: he spoke to children and answered their questions only in Serbian, and the mother spoke and answered in French. And it turned out that neither the degree of improvement in both of these languages, nor the pace of advancement in both of these languages, does not suffer from the presence of two languages at the same time. Also valuable are the studies of Iorgen, who covered 16 children and showed that three languages are learned with the same ease, without mutually inhibiting influence of one on the other.

Summing up the experiences of teaching children to read and write at an early age, the Leipzig and American schools come to the conviction that teaching children to read at 5-6 is easier than teaching children at the age of 7-8, and some data from Moscow studies say the same: they showed that literacy in the ninth year faces significant difficulties compared to children who learn at an early age.

The memory of a child at an early age cannot be compared with the memory of a teenager, and especially with the memory of an adult. But at the same time, a child at three years old, who learns foreign languages more easily, cannot acquire systematized knowledge from the field of geography, and a schoolboy at 9 years old, who hardly learns foreign languages, easily learns geography, while an adult surpasses a child in memory to systematized knowledge.

Finally, there were psychologists who tried to take the middle in this matter. This group, occupying the third position, tried to establish that there is such a point when memory reaches a climax in its development. In particular, Seidel, one of the students of Karl Gross, covered a very large amount of material and tried to show that memory reaches its height in 10 years, and then it begins to slide down.

All these three points of view, their very existence, show how simplified the question of the development of memory in these schools is. The development of memory is considered in them as some simple movement forward or backward, as some ascent or rolling, as some movement that can be represented by one line not only in a plane, but also in a linear direction. In fact, approaching the development of memory with such a linear scale, we are faced with a contradiction: we have facts that will speak for and against, because the development of memory is such a complex process that it cannot be represented in a linear cut.

In order to move on to a schematic outline of the solution to this problem, I must address two issues. One is covered in a number of Russian works, and I will only mention it. It is about an attempt to distinguish two lines in the development of children's memory, to show that the development of children's memory does not follow one line. In particular, this distinction has become the starting point in a number of memory studies with which I have been involved. In the work of A.N. Leontiev and L.V. Zankov provided experimental material confirming this. The fact that psychologically we are dealing with different operations, when we directly memorize something and when we memorize with the help of some additional stimulus, is beyond doubt. That we remember differently when, for example, we tie a knot for memory and when we remember something without this knot, is also beyond doubt. The study consisted in the fact that we presented children of different ages with the same material and asked him to memorize this material in two different ways - the first time directly, and the other a number of auxiliary means with which the child had to memorize this material was distributed.

An analysis of this operation shows that a child who memorizes with the help of auxiliary material builds his operations on a different plane than a child who memorizes directly, because a child who uses signs and auxiliary operations requires not so much the power of memory as the ability to create new ones. connections, a new structure, a rich imagination, sometimes well-developed thinking, that is, those psychological qualities that do not play any significant role in direct memorization ...

Research has shown that each of these methods of direct and indirect memorization has its own dynamics, its own development curve ...

What is theoretically valuable in this distinction and what led to the fact that theoretical research has confirmed this hypothesis is that the development of human memory in historical development proceeded mainly along the line of mediated memorization, that is, that a person developed new techniques, with with the help of which he could subordinate memory to his goals, control the course of memorization, make it more and more volitional, make it a reflection of more and more specific features of human consciousness. In particular, we think that this problem of mediated memorization leads to the problem of verbal memory, which plays an essential role in a modern cultured person and which is based on memorizing the verbal recording of events, their verbal formulation.

Thus, in these studies, the issue of the development of children's memory was shifted from a dead center and transferred to a somewhat different plane. I do not think that these studies have settled the question conclusively; I am inclined to believe that they rather suffer from colossal simplification, while at the beginning I heard that they complicate the psychological problem.

I would not like to dwell on this problem as already known. I will only say that these studies lead directly to another problem that I would like to make central in our studies - a problem that is clearly reflected in the development of memory. The point is that when you study mediated memorization, that is, how a person memorizes, relying in his memorization on well-known signs or techniques, then you see that the place of memory in the system of psychological functions is changing. What, in direct memorization, is taken directly by memory, in indirect memorization, it is taken with the help of a number of mental operations, which may have nothing to do with memory; there is, therefore, a sort of substitution of some mental functions by others.

In other words, with a change in the age level, not only and not so much the structure of the function itself, which is designated as memory, changes, but the nature of those functions with the help of which memorization occurs, changes between functional relations that link memory with other functions.

In our first conversation, I gave an example from this area, to which I will allow myself to return. It is remarkable not only that the memory of a child of a more mature age is different from that of a younger child, but that it plays a different role than in the previous age.

Memory in early childhood is one of the central basic mental functions, depending on which all other functions are built. Analysis shows that the thinking of a young child is largely determined by his memory. The thinking of a young child is not at all the same as the thinking of a more mature child. For a young child, thinking means remembering, that is, relying on one's previous experience, on its modifications. Thinking never shows such a correlation with memory as it did at a very early age. Thinking here develops in direct dependence on memory. Here are three examples. The first concerns the definition of concepts in children. The child's definition of concepts is based on recollection. For example, when a child answers what a snail is, he says that it is small, slippery, it is crushed with a foot; or if a child is asked to write about what a bunk is, he says that it has a "soft seat". In such descriptions, the child gives a succinct sketch of the memories that reproduce the subject.

Consequently, the subject of the mental act when denoting this concept for a child is not so much the logical structure of the concepts themselves as memory, and the specific nature of children's thinking, its syncretic nature - this is the other side of the same fact that children's thinking is primarily based on for memory ...

Recent research on the forms of children's thinking about which Stern wrote, and above all research on the so-called transduction, that is, the transition from a particular case to another, also showed that this is nothing more than a recollection of another similar a particular case.

I could point to the last pertaining to this - the nature of the development of children's ideas and children's memory at an early age. Their analysis, in fact, refers to the analysis of the meanings of words and is directly related to our still upcoming topic. But in order to build a bridge to her, I wanted to show that research in this area shows that the connections behind words are fundamentally different between a child and an adult; the formation of the meanings of children's words is structured differently from our ideas and our meanings of words. Their difference lies in the fact that behind any meaning of words for the child, as well as for us, there is a generalization. But the way in which the child generalizes things and the way in which you and I generalize things are different from each other. In particular, the method that characterizes children's generalization is directly dependent on the fact that the child's thinking is entirely based on his memory. Children's performances related to a number of subjects are built in the same way as we have family names. The names of words, phenomena are not so much familiar concepts as surnames, whole groups of visual things connected by visual connection ... However, a turning point occurs during childhood development, and a decisive shift here occurs near adolescence. Studies of memory at this age have shown that by the end of childhood development, the inter-functional relations of memory change radically in the opposite direction, if for a young child to think is to remember, then for a teenager to remember is to think.

His memory is so logical that memorization is reduced to the establishment and finding of logical relationships, and remembering is to search for the point that must be found.

This logic represents the opposite pole, showing how these relations have changed in the process of development. In a transitional age, the central point is the formation of concepts, and all ideas and concepts, all mental formations are no longer built according to the type of family names, but, in fact, according to the type of full-fledged abstract concepts.

We see that the very dependence that determined the complex nature of thinking at an early age further changes the nature of thinking. There can be no doubt that memorizing the same material for a thinker in concepts and a thinker in complexes are completely different tasks, albeit similar to each other. When I memorize some material lying in front of me with the help of thinking about concepts, that is, with the help of abstract analysis, which is contained in thinking itself, then I have a completely different logical structure in front of me than when I study this material with the help of others. funds. In one and the other case, the semantic structure of the material is different.

Therefore, the development of children's memory should be studied not so much in relation to the changes occurring within the memory itself, but in relation to the place of memory in a number of other functions ... Obviously, when the question of the development of children's memory is posed in a linear cut, this does not exhaust the question of memory. development.

Vygotsky L.S. Memory and its development in childhood / Vygotsky L.S. Sobr. Op. in 6 volumes - T.2. - Problems of general psychology. - M .: Pedagogy, 1982. -S. 386-395.